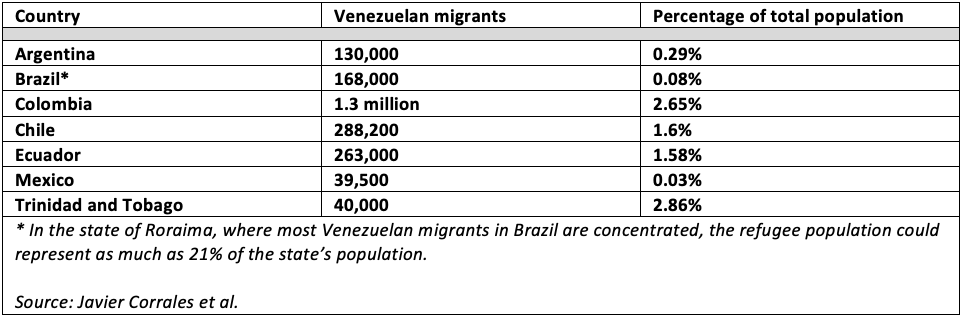

The Venezuela crisis, perhaps the largest economic collapse outside of war in over four decades, has unleashed one of the most massive migration flows in the world. According to the United Nations, as of June 2019 over four million people had fled the country, with an average 5,000 leaving every day in 2018. Over 80% of Venezuelan migrants have settled in Latin American and Caribbean nations, many of which have never seen migration of this size before.

With the intense impact felt across the region, one would think the response would be fairly unwelcoming in an era of rising nativism globally and anemic economic growth regionally. The initial response though, was mostly positive. But signs of strain are increasing. With a group of students, we conducted research on seven countries, and found examples of both good and bad responses as well as signs of backlash.

Survival Services

Much of the discussion focuses on the provision of survival services, such as food, healthcare, shelter, legal counseling and labor market insertion. Most Venezuelan migrants are now poor and low skilled, and therefore arrive in need of multiple social services. But providing social services is enormously costly for governments, already strapped for resources.

Although most countries provide at least minimal services, and many are collaborating internationally to secure more help from abroad, surveys report that most migrants are not receiving enough survival services. In countries where Venezuelan immigrants represent more than 1.5% of the total population (Ecuador, Chile, Colombia, Trinidad and Tobago, and the state of Roraima in Brazil) the strains are already visible. Some governments have had to rely excessively on international organizations (especially Ecuador), or even mobilize the military to help with logistical and humanitarian operations, as in Brazil. Both are signs of desperation.

Legal Facilities

Welcoming migrants also involves providing legal options for entry and residence. For Venezuelans, a valid passport is onerous, if not impossible, to obtain. The Venezuelan government has long had major delays – and unduly high fees – in issuing passports. Starting in 2017, the country suspended passport appointments and renewals indefinitely due to a shortage of necessary materials. It’s even harder for Venezuelans to procure other legal documents such as police reports certifying good conduct, an entry requirement for more restrictive countries like Ecuador.

Argentina is setting a good example as one of the few Latin American countries that does not require a visa and passport for Venezuelans to enter the country. In late February 2019, more facilities were established for Venezuelans to obtain a temporary visa even if they were unable to secure all the necessary documents. The government is even matching immigrants with jobs across the country.

Colombia comes next. While Colombia does have a passport restriction for entry, Venezuelan passports are allowed to be expired up to two years. In August 2018, Colombia provided 440,000 migrants temporary residence, which included access to emergency medical care, a social security system, prenatal care, assistance in finding employment, and schooling for children. Additionally, the Colombian government offers Venezuelans living near the border a Tarjeta de Movilidad Frontizera (TMF), which allows for short trips into Colombia, as well as a 15-day transit permit option – giving Venezuelans a legal pathway to migrating through Colombia to another destination.

At the other end of the spectrum are Trinidad and Tobago and, to some extent, Mexico. Trinidad and Tobago requires Venezuelans to have both a passport and a visa. An amnesty was offered to Venezuelans living in the country illegally, but the window for applying was too brief (two weeks) and the benefit entailed permission to work for only one year. And although Mexico has offered asylum to many Venezuelans, the country is increasingly adopting restrictive responses to all immigrants, not just Venezuelans, partly in response to U.S. pressure.

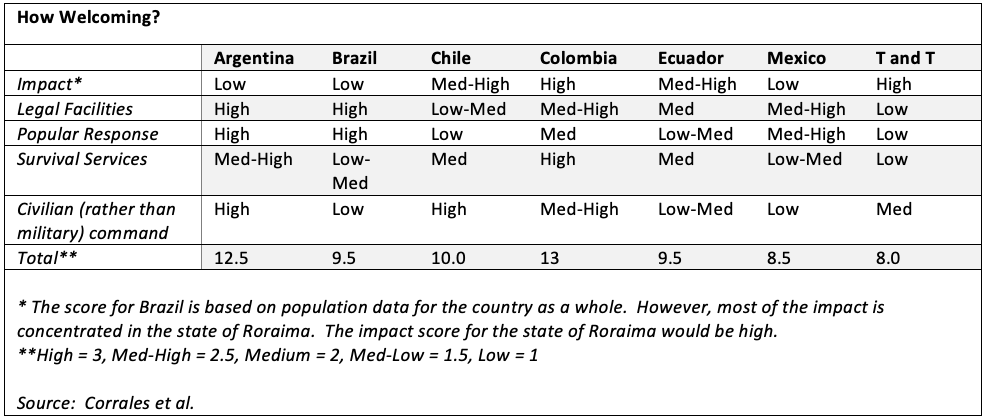

The Scorecard

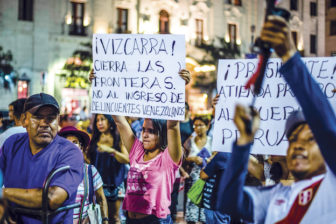

Public Attitudes

Most Venezuelans encounter far more security and job opportunities abroad than at home. But signs of nativist popular attitudes are increasing. A report from Argentina showed that about 38% of respondents had witnessed discriminatory behavior towards Venezuelans. In Brazil, there have been reports of violence, including the forced removal of 1,200 Venezuelans from Pacaraima by local citizens. Colombia too has reported mob violence, protests and crimes in areas where Venezuelan migrants are concentrated. In Chile, according to a survey by the National Institute of Human Rights, 68% of Chileans want to restrict immigration, and a different survey found that 75% of respondents thought the number of immigrants was excessive.

Despite all these rising problems, the evidence so far points toward more positive than negative responses. Of the seven countries examined, those with the most welcoming response overall have been Colombia, Argentina, and to a lesser extent Ecuador and Brazil.

What explains this positive general reaction? The answer is a combination of external and domestic factors.

The Role of International Norms: The 1984 Cartagena Declaration

The generally positive reaction is mostly an example of international norms doing their job. Most of the affected countries are signatories of the 1984 Cartagena Declaration or the follow-up 2014 Brazil Declaration. These are landmark international statements, drafted under the auspices of the United Nations, that expand the definition of refugees to include not just individuals directly facing persecution, but also broad categories of humans facing risk situations. The accord commits signatories to provide “assistance to refugees, particularly in the areas of health, education, labor and safety.”

Few other regions in the world have adopted this broad norm about refugees. In Latin America, even though most governments have fallen short of fully adopting the Cartagena Declaration – adopting instead some restrictions and ad hoc responses – the Declaration still acts as an important check on nativism. Courts, civic organizations, and some politicians often invoke the principles of the Declaration to challenge nativist responses from governments or ordinary citizens.

The Role of Foreign Policy and Leadership

Another factor is the receiving country’s foreign policy. Of the two most highly impacted neighboring countries, Colombia and Trinidad and Tobago, the latter has taken the harsher approach cracking down on illegal immigrants and deporting a good number of asylum seekers. One reason for Trinidad and Tobago’s harsh approach is that the government maintains economic ties with the Venezuelan oil industry. The government has not broken formally with Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro and refuses to recognize Venezuelans as refugees.

Finally, presidential leadership matters. Ruling parties and especially the president have enormous influence in directing the political climate of a country. Consequently, a ruling party’s discourse vis-à-vis Venezuelan migration – almost as much as their policies – can directly affect levels of societal nativism.

President Iván Duque in Colombia and President Mauricio Macri in Argentina have been vocal in their defense of Venezuelan migrants. Macri made the remarkable decision to treat Venezuelans as citizens of Mercosur, which gives them a path to residency, even though Mercosur formally suspended Venezuela’s membership in 2017.

Other presidents have demonstrated far less commitment, even when taking a stance against Maduro. Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro, for example, mentioned that his country would be pulling out of a UN migration accord, claiming that Brazil needed to take “rigid control” of its border. Ecuador’s Lenín Moreno, who also broke with Maduro, issued an announcement that he would not allow immigration “to sacrifice anyone’s safety” after a violent incident.

Conclusion

Institutions and public attitudes in Latin America are being tested by the Venezuelan crisis. Immigration already became a divisive issue in the 2017 Chilean election, with one of the main candidates openly adopting an anti-immigrant discourse. Fortunately, the region is protected by pro-immigrant international norms, strong civil organizations and sympathetic politicians. But these defenses may not be enough to contain the rise in nativism that is resulting from Latin America’s worst migration crisis in decades.

—

Corrales is a Professor of Political Science at Amherst College and member of AQ’s editorial board. Avery Allen, Lakeisha Arias, Manuel Rodríguez, and Logan Seymour assisted on the research and the report.