“South America for the South Americans!” a confident President Hugo Chávez cried at a packed rally in Buenos Aires in March 2007. It is not without irony that, little more than a decade later, the policies of the late Venezuelan leader and his successor have achieved the exact opposite. The oil-rich nation is experiencing a humanitarian catastrophe and an unprecedented exodus, and the four most influential outside actors in Venezuela today are not from the continent, namely China, the United States, Russia and Cuba. South American leaders have been reduced to mere bystanders as the horror in Venezuela unfolds, even though they are by far the most affected as their countries take in an ever-growing Venezuelan diaspora.

South America as a whole has failed Venezuela. But its implosion has been a dramatic change of fortune for Brazil in particular, a country that until recently aspired to play the role of regional leader and crisis manager-in-chief. The country has only itself to blame. During Lula’s two terms as president (2003-2010), Venezuela’s self-destruction was entirely predictable but still avoidable. But the Brazilian leader did not just fail to coax Chávez into changing course. Instead – enticed by significant short-term economic gains from booming trade and juicy infrastructure contracts – Brazil played the role of an enabler, protecting Venezuela from outside diplomatic pressure and assuring worried diplomats from around the world that it could handle its unruly neighbor. As a former high-ranking U.S. diplomat remembers, “What (former President George W.) Bush was hearing from … Lula da Silva was: Don’t worry about Hugo, I have him in my hand.” Under former President Dilma Rousseff and current President Michel Temer, political and economic crises in Brazil created a regional power vacuum that strengthened the growing global perception that policymakers in Brasília and the region would be unable to stop Venezuela’s slide into chaos.

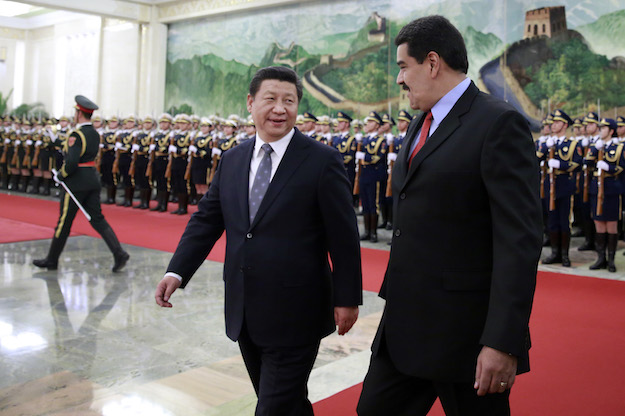

Brazil’s failure has crucial and not yet fully appreciated long-term consequences for South American geopolitics, reducing the continent’s capacity to shape its own destiny, and opening the door to heavy-handed outside intervention. In the past, regional crises were mostly debated during Mercosur or UNASUR gatherings. Today, the best opportunities for regional leaders to influence the situation in Caracas are no longer regional summits, but bilateral meetings in Beijing, Moscow or Washington, D.C. Remarkably, it will be the 10th BRICS Summit in Johannesburg in July, a meeting traditionally used to discuss broad topics like the future of global order, where an enfeebled Temer must make his case vis-à-vis Venezuela to Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin, who are crucial to keeping the Maduro government afloat – or at least find out what Russia’s and China’s Venezuela strategies will be over the next months and years to better articulate Brazil’s response. In the same way, the crisis in Venezuela now occupies precious bandwidth when South American diplomats bilaterally engage with their U.S. counterparts, reducing the time available for other key issues.

This situation is unlikely to change even in the medium or long term, no matter how long the current government in Caracas remains in power. The most likely scenario is that Maduro or someone proffering similar policies stays in charge for years to come, piloting a large passenger aircraft low on fuel as it descends very slowly toward the ocean. How soon it hits will depend largely on the extent of Russian and Chinese financial and political support, as well as on the United States’ appetite to go beyond individual sanctions. The result will be a continued refugee outflow into the rest of South America, with Colombia the most severely affected, followed by Argentina, Peru, Brazil, Chile and others, as well as instability along Venezuela’s borders.

The continuation of the status quo seems especially plausible because the distribution of political power in Venezuela suggests that few key players face a strong incentive to change course at this stage. The armed forces control the distribution of food and medicine and reap enormous benefits on the black market thanks to government-imposed price distortions. Around 10 percent of the population is thought to have emigrated, and every additional Venezuelan who decides to leave reduces the probability that organized protest will engender an effective opposition movement. A U.S. government move to stoke division within the Venezuelan armed forces, or to impose an oil embargo that could block 40 percent of PDVSA’s exports, is unlikely to lead to regime change and the return of democracy, despite what some in Washington suggest. It would, however, increase the refugee flow into neighboring countries, enhance Caracas’ dependence on China and Russia, and boost domestic support for Maduro by confirming his anti-American rhetoric as he blames outside actors for the country’s plight.

Yet even in the highly unlikely scenario of a quick collapse of the Maduro regime and the organization of free and fair elections, South American leaders will have to get used to powerful extra-regional actors operating in Caracas. Any future Venezuelan government would probably need to sign long-term deals with both the IMF and Chinese banks to initiate the lengthy process of reconstruction. Development agencies from around the world would come to Caracas, given the new government’s tremendous shortage of even minimally-trained bureaucrats. With an entire generation of Venezuelans decimated by lack of schooling, malnutrition and untreated diseases once thought of as a thing of the past and a sizeable number of recent refugees unlikely to return, recovery to anything resembling pre-crisis levels is likely to take more than a decade.

Future historians will view this crisis as a tremendous setback in South America’s long quest to manage its own affairs and reduce outside influence.