Asked about the effects of conflict, the old Colombian patriarchs used to repeat that “the country is in bad shape, but the economy is doing well.” The wave of protests over the past two weeks have shown how false this notion can be. Political tensions have affected the economy in the past – and will have an effect moving forward.

With one of the highest growth rates in Latin America, Colombia is reaping the benefits of a well-managed adjustment to the 2014-2016 collapse in oil prices. Thus, at first glance, it may look paradoxical that the new chapter of the social unrest in the region has been taking place in Colombian cities. Street mobilizations and cacerolazos are becoming a constant, while negotiations with the government are moving slowly.

One of the explanations for Colombia’s above-average performance in Latin America is that, despite increasing political polarization, its macroeconomic policies have remained stable and coherent for several years.

GDP growth increased from 2.8% in the second quarter of 2018 — prior to Duque’s inauguration — to 3.3% in the third quarter of 2019, despite a sharp deceleration in exports. Growth is being driven by domestic demand, notably private consumption and investment. Although consumer sentiment continues to be negative, retail sales of durable goods and other products have been on the rise. Public works, which are rapidly expanding due to the 4G infrastructure program, are also contributing to the economic momentum.

In other words, key nontraded sectors, such as retail, financial activities, transport and public works are sustaining the expansion, reflecting historically low interest rates at 4.25% since April 2018. The 4G infrastructure program also has received wide political support and adequate financing, and most importantly, household consumption picked up after the sharp depreciation that resulted from the collapse in oil prices.

But not everything looks good. Mixed signals make the Colombian economy hard to read.

Unemployment has been on the rise, reaching 9.8% this past October, in contrast to 8.6% two years ago. This is in part explained by a sharp contraction in housing construction, which fell 11.1% in the third quarter (Q3) of 2019.

Falling exports have also negatively impacted manufacturing output, which grew only 1.5% in the third quarter. Other traded sectors, such mining and agriculture, are also underperforming.

The key takeaway of this scenario is that the current economic expansion lacks the comprehensiveness of previous growth periods. Given the rise in unemployment and the decline in consumer confidence, the expansion can be derailed. If protests are not managed well, they can be very costly for the economy. This can result from a negative effect on expectations, curbing the expansion in consumption and retail. The risk can also arise if, in response to pressures, the government takes wrong economic and political decisions, like an excessive increase in the minimum wage that can result in higher unemployment.

A few banks are already reporting lower growth in consumer credit associated with a deterioration in consumer confidence. Unless negotiations between the government and leaders of the mobilizations move forward, the economy will suffer.

What is driving the unrest?

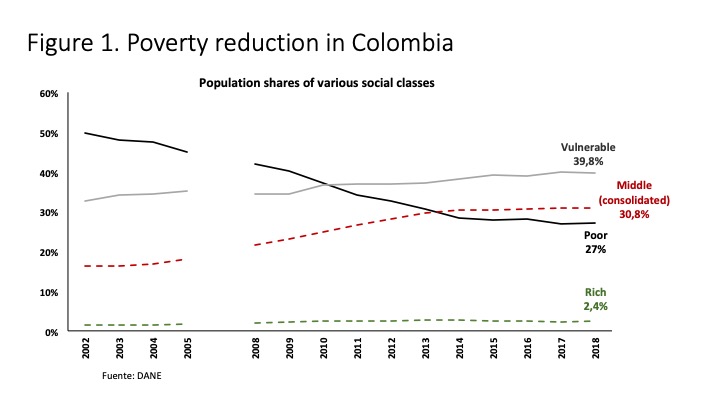

This graphic shows that the vulnerable middle class – individuals above the poverty line but below the consolidated (or safe) middle class – accounts for nearly 40% of Colombia and is the largest demographic group in the country. For them, income and jobs do not provide enough economic security. The risk of falling back to poverty, especially in a low growth and high unemployment environment, is a feature of daily life. Colombians that have taken to the streets are primarily from this group and are expressing the anxiety associated with their current situation.

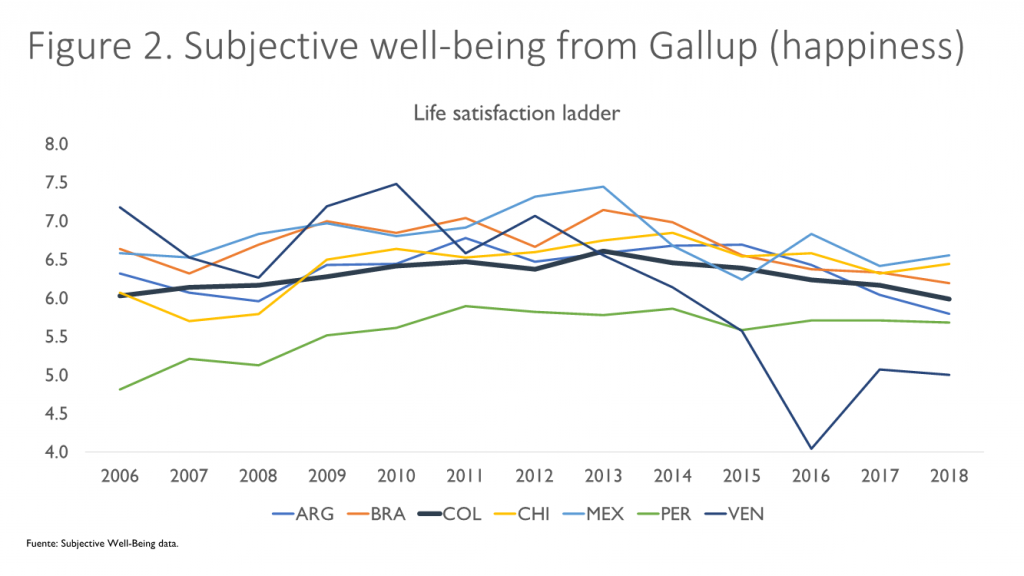

In addition, subjective well-being (SWB), or happiness, has decreased rapidly in Colombia, as in almost every country in Latin America. The World Happiness Report 2019 shows that SWB fell in Colombia to an average score of 6 (in a 0-to-10 scale) in 2018 from 6.6 in 2013.

This 10% decline followed the change in the Latin American average, with Mexico, Brazil and Argentina experiencing faster declines. Interestingly, this has not happened in other parts of the world (such as East Asia, Central and Eastern Europe, and Africa) where SWB has continued to increase. As Patricio Navia put it, many Latin Americans are waiting at the gates of the promised land of the middle class. I would add that the queues are getting longer – and the fear of a return to poverty is increasing.

Colombians – and Latin Americans in general – feel frustrated due to slower growth of the economy and in employment, while their aspirations continue to rise. The fact that some other wagons are moving forward creates the perception that the region’s train is moving backward, even if it is still progressing.

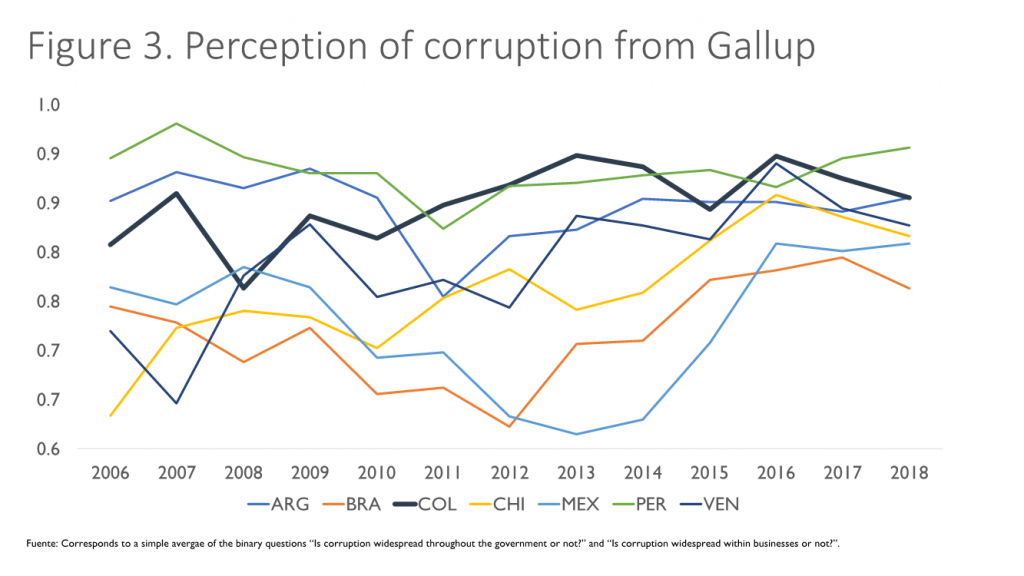

Another critical area is the perception of corruption. The graphic above shows the average of the binary answers to two questions: “Is corruption widespread throughout the government or not?” and “Is corruption widespread within businesses or not?”. Results show that the perception of corruption is generalized in Latin America, but particularly high in Peru and Colombia. Nearly 85% of Colombians give a positive answer to these questions, indicating that grievances related to lack of transparency are likely a serious factor behind the social unrest.

Fixing the problem

Against this backdrop, the victory of opposition candidates in several Latin American countries that held elections in 2018 and 2019 was unsurprising. Colombia was no exception. What is interesting is that the same majorities that elected President Duque are demanding from him a change.

The first step to reset relations between the government and large sectors of society should be the implementation of the peace agreement with the FARC. The deal was a divisive issue in the 2016 plebiscite and the 2018 presidential and congressional elections, but it now generates more support than before. Governors and mayors elected this past October, as well as local legislative bodies, did express their support for the agreement. And those that did run under the umbrella of the anti-peace agreement movement, generally lost.

A second step is updating the agenda to reduce poverty and inequality. Inequality in Colombia is still one the highest in the hemisphere. The Gini coefficient is much higher than what the country’s level of per capita income would predict. Moreover, taxes and government expenditures do not reduce inequality, mostly because pensions are heavily concentrated in the top 20% of the population.

President Duque announced three measures last week aimed at generating popular support: Three days per year without VAT, the reimbursement of the VAT paid by the bottom 20% of households, and the reduction of four percentage points in the 12% mandatory contribution that pensioners need to make for health insurance (in two years another four percentage points will be scrapped). To make this measure less regressive, it will apply only to those receiving pensions equal to the minimum wage. Of these measures, only the one related to the VAT reimbursement has the potential of reducing income inequality.

What is needed is boosting programs that have demonstrated impact in reducing poverty and inequality, such as early childhood intervention and a subsidy to the elderly in extreme poverty. Both of these programs exist but they still do not cover all the targeted population. Also, contemplating students’ demands, a larger share of royalties from energy and mining should go to tertiary education. The youth is leading the current uprising and their preferences should be reflected in budgetary allocations, which in Colombia are heavily biased towards pensions.

In a different vein, a change needs to be made on communications. The government has failed to listen to those on the receiving end of its policies. For example, the government has been promoting a tax reform reducing corporate taxes to boost growth. However, many observers – including a long list of economists at the main Colombian universities – have serious and legitimate concerns that this could affect negatively fiscal revenues. Without fiscal capacity to deal with social needs in the medium term, the problems of social unrest today could pale in comparison to those that can arise in the future.

The assumption must be that the public demands good explanations and more representation, particularly the youth. The current paternalistic view that “we know better what is best” is a recipe for disaster. More dialogue, more listening and more engagement is needed to defuse the widespread outrage. And this calls for strengthening our democratic institutions to increase political participation.

—

Cárdenas is a former Colombian finance minister and currently a Visiting Senior Research Scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.