This piece has been corrected.

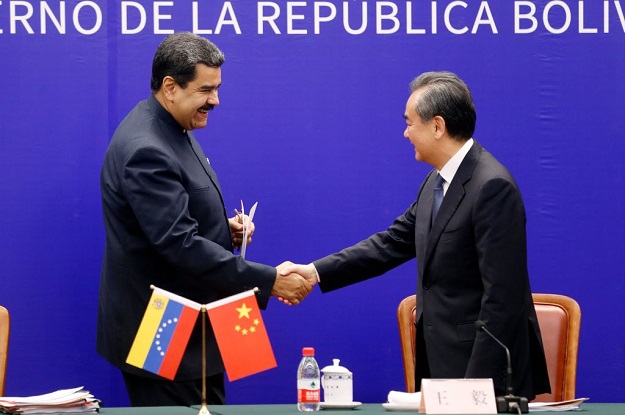

SHANGHAI – Nicolás Maduro’s visit to Beijing in September was front page news in Caracas, as the Venezuelan leader trumpeted China’s willingness to extend a $5 billion credit line to its cash-strapped South American ally.

For Maduro, meetings with President Xi Jinping and the Chinese premier, Li Keqiang, helped challenge Venezuela’s portrayal as a global pariah, and validated his promises of “big achievements” during the trip.

Inside China, however, Maduro was a ghost. State media ignored the visit, according to analysts who are usually called upon to discuss the government’s high-level Latin America engagements. Government statements made no reference to the credit line, leading observers to wonder whether Maduro had invented the loan.

In part, these distinct communications strategies reflect the different interests and styles of the Chinese and Venezuelan governments. But there is another explanation, which should trouble the Venezuelan regime: Beijing’s relationship with Venezuela is increasingly unpopular with the Chinese population, and it is regarded as an extravagant waste of public resources.

In China, public criticism of foreign policy is rare and most debate is restricted to social media, where users grumble that aid to Venezuela’s corrupt and incompetent leaders would be better spent on social programs at home, as well as health care, rural development and poverty reduction.

Some scholars have raised concerns publicly. Two years into Maduro’s rule, Li Xue, of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, warned about excessive lending to Latin American governments, noting the high risk of default. Last year, Zheng Shujiu, of the Beijing Foreign Studies University, published an analysis arguing that China had misjudged the investment climate in Venezuela.

Between 2005 and 2017, the China Development Bank and China Export-Import Bank have loaned more than $62 billion to Venezuela, according to Inter-American Dialogue data – just over forty percent of all the banks’ loans to Latin America. Chinese loans boosted former Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez’s 2012 re-election campaign and helped keep the country afloat after oil prices crashed in 2014.

But of late, as Venezuela stumbled into hyperinflation, that lending has slowed considerably. In recent years, Chinese support has focused on keeping Venezuela’s flagging oil sector operational so that the state oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), can keep oil flowing to China to repay previous loans.

Though Venezuela holds the world’s largest oil reserves, declining production has jeopardized its ability to meet its obligations to Beijing. Last month, oil production fell by 40,000 barrels per day, to 1.12 million barrels per day, according to OPEC, down from 3.5 million barrels a day when Chávez was elected in 1998.

Still, there are reasons to doubt China would ever abandon Venezuela.

Since the 1980s, China has generally paired its growing economic might with a low-profile foreign policy. That was especially true in Latin America, for fear of antagonizing the United States.

But Chinese scholars now acknowledge the geopolitical importance of Venezuela, as it gives China influence in a region dominated by the United States. Venezuelan oil is also prized by Beijing, as it helps diversify suppliers and increases China’s bargaining power with other oil providers. Moreover, Chinese scholars say, admitting failure in Venezuela would call into question Xi’s “win-win” model of international cooperation, which is light on conditionality and defers to local authorities to identify priorities.

Chinese foreign policy also prizes loyalty, and it now regards Venezuela as an old friend.

Indeed, even as Venezuela’s economy has disintegrated, sparking a humanitarian crisis and exodus, China has avoided coordination with the United States on any global response.

That does not mean China isn’t having second thoughts. After all, Chinese analysts are hardly the only observers who object to Beijing’s Venezuela policy. Human rights defenders, for example, see China as an obstacle to any United Nations Security Council action on Venezuela, where the repressive regime earned a complaint to the International Criminal Court in September, filed by five Latin American governments.

Finally, Beijing is working overtime to counter U.S. warnings that Chinese lending, including through its signature Belt and Road Initiative, is “predatory,” and designed to ensnare borrowers in a “debt trap.” The counterargument – that China meticulously vets development projects to assure repayment – is undermined by its multibillion-dollar bet on Venezuela.

Should Venezuela discontinue oil shipments to China, any debt collection efforts would reverberate globally, as did China’s notorious takeover, for nonpayment, of a Chinese-built Sri Lankan port. Malaysia’s new leader, Mahathir Mohamad, has also raised questions about Chinese lending, as he reconsiders multibillion energy and transportation megaprojects inherited from his predecessor.

Publicly, there is little daylight between the Chinese and Venezuelan leaders. But notably, in recent years, the Chinese government has begun meeting with Venezuelan opposition leaders, who would decide whether to honor Venezuela’s debts in the event of a political transition. And despite the depths of Venezuela’s economic collapse, China has never offered a moratorium on Venezuela’s oil debt service.

“The Chinese realize that they have dug themselves into a very deep hole in Venezuela,” Fernando Cutz, President Trump’s former South America adviser, said in recent remarks. “The Chinese are fully convinced that Venezuela is a box they don’t want to be anywhere close to anymore. They just want their money back.”

A previous version of this piece referred to Malaysian prime minister Mahathir Mohamad as Myanmar’s new leader.

—

Gedan, a former South America director on the National Security Council, is the senior adviser to the Latin American Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and an adjunct lecturer at Johns Hopkins University.