A bloated informal sector has long been a nagging structural problem in Latin America and in the developing world more generally. However, over the past few decades, it has proliferated as a result of the withdrawal of the state from market and social regulation. In particular, it has grown as governments have undertaken structural adjustment and free-market reform, rolled back social protections for workers and reformed labor laws to make labor more flexible.

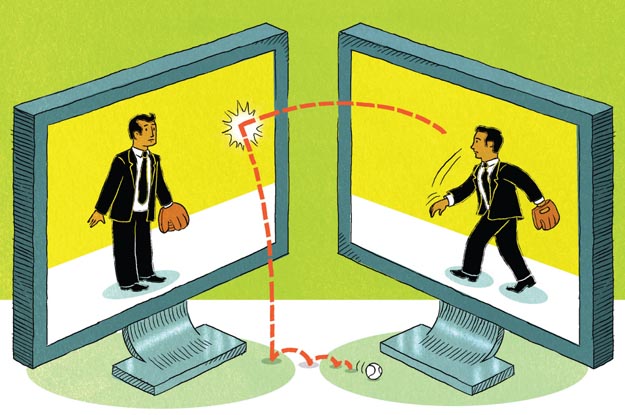

The so-called sharing economy, which has given rise to new forms of self-employment such as Airbnb and Uber, may make available new income streams for some sectors. But there is nothing in the nature of these services that will draw those who work in these activities into the formal sector, absent government regulation of these services.

Governments in nearly every Latin American country revised labor laws in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.1 These modifications have contributed to the changing nature of employment in the region, particularly the spread of flexible work and unregulated labor markets. Even as the emergence of the global economy generated new investment and employment opportunities in the region, these jobs have involved largely precarious and unstable employment. The International Labor Organization calculated in 2005 that of every ten new jobs created in the 1990s, eight were in low-quality positions in the informal sector.2

The majority of Latin America’s urban labor force worked in the formal sector during the period of national developmentalism that lasted from the end of World War II into the 1970s. In 1950, 69.2 percent of urban workers in Latin America worked in the formal sector. This figure increased to 70.2 percent in 1970—ranging from a high of 80.9 percent in Argentina to a low of 42.1 percent in Ecuador.3

By the 1980s, the urban labor force working in the formal sector had declined to 59.8 percent. By 1985, it had dropped to 53.1 percent, and by 1998 to just 42.1 percent.4 At the same time, employment in small firms and self-employment increased sharply throughout the region, indicating both a shift from formal sector employment to self-employment in the informal sector, and the increased reliance of large firms on outsourcing and subcontracting to small enterprises that generally operate under informal conditions.

The data show that informality increased to the extent that governments withdrew from labor markets and social regulation, as the new global model of subcontracted and outsourced labor spread. There has been an explosion of people who scratch out a living by providing whatever service they are able to market, since the informal sector has been the only avenue of survival for millions of people thrown out of work by the contraction of formal-sector employment and by the uprooting of remaining small farming communities.

Furthermore, research has shown that the informal sector is now functionally integrated into the formal sector through a variety of mechanisms and relationships. Enterprises in the formal sector draw on informal-sector activity for a wide variety of services. Moreover, an increasing portion of what was formal-sector work has been contracted out to small and generally unregulated businesses or to individuals on a piecemeal and informal basis.5 It’s a mistake, therefore, to see the informal sector as lacking market integration. Rather, this form of market integration is unregulated.

Where does this reality leave sharing economy platforms such as Airbnb and Uber? These platforms are not necessarily bad ideas. The point is that while Airbnb and Uber may offer consumers more convenient and perhaps more affordable—housing and chauffeuring options, they really have nothing to do with helping to formalize Latin America’s informal sector.

Leaving aside that most poor people in the informal sector in Latin America have neither cars to chauffeur people around nor comfortable housing for international travelers, these platforms are entirely unregulated in terms of employment. There is every reason to expect, for example, that maids, cooks and petty service providers drawn from the informal sector will provide the labor for Airbnb services in Latin America. Furthermore, given that hotel and taxi work are—for the most part—still regulated economic activities in terms of employment, safety, etc., a shift from hotels and taxis to Airbnb hosts and Uber drivers may actually expand rather than reduce the informal sector.

Ultimately, the question of whether the sharing economy will help formalize Latin America’s informal sector points us in the wrong direction. It draws attention away from the more fundamental problem—the informalization and casualization of labor as the consequences of a global economy liberated from social regulation—and from the need to re-impose social protections.