Geopolitics is going online. While observers in Brazil focus on the ongoing trade war between the United States and China, an incipient tech war is poised to have far broader consequences for the future of the global order and Latin America’s place in it.

Rapid technological change, symbolized by the arrival of 5G mobile technology, artificial intelligence and quantum computing, is fast becoming the defining element in an emerging great-power standoff, marked by the battle for supremacy in cyberspace between the United States and China. Already, the key dynamic in global affairs is no longer trade liberalization and open competition – concepts embraced by Brazil’s Economy Minister Paulo Guedes – but the geopoliticization of the world economy and the race towards technological self-reliance.

The debate about what Brazil’s strategy should be in such an unprecedented global scenario has just begun, with the government in Brasília already under intense pressure from both Washington and Beijing about whether or not to exclude the Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei as a potential provider of 5G technology. Along with India and Indonesia, Brazil, with roughly 210 million inhabitants, is seen as one of the most important markets in defining the future of 5G in the developing world.

The coming tech split is set to accelerate and deepen “decoupling” – the declining economic interdependence between the world’s two largest economies – and exacerbate Western companies’ aversion to the geopolitical risk that operating in China implies. This development could bring about the emergence of two separate economic camps, reversing the tremendous economic globalization that has been the hallmark of international order in recent decades. U.S. companies like Apple, which depend on China, will be affected as much as Chinese tech companies such as Huawei, which use countless U.S. components.

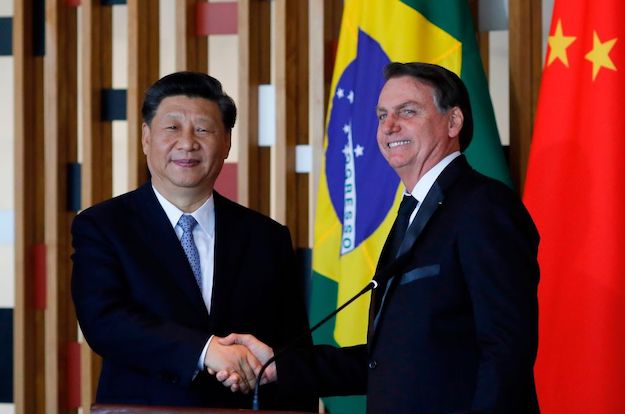

For countries like Brazil, traditionally averse to taking sides or being tied down in alliances and always seeking to carve out a maximum amount of strategic autonomy, this new scenario will involve hard choices. While President Jair Bolsonaro and his closest advisers favor strengthening ties to the United States, Brazil is economically dependent on China, which has been its most important trade partner since 2009.

Brazil has long used its ambiguous geopolitical role in its favor, remaining on good terms with almost everyone. It is one of few countries in the world that can, in theory, play a relevant role within non-Western outfits such as the BRICS or the G77, as well as Western-led groups such as the OECD, where it currently seeks membership. Leaders like Chile’s Sebastián Piñera have similarly sought to maintain strong ties to both the United States and China, despite growing tensions between presidents Donald Trump and Xi Jinping. Latin America has so far been less affected by great power competition than the rest of the world – but that advantage may soon disappear given the emerging technological standoff between China and the United States.

While the public debate over 5G, Huawei and its geopolitical implications is well underway in Europe, it has only recently moved onto the public radar in Brazil. In November 2019, the 5G portfolio was shifted from the National Telecommunications Agency (Anatel) to the president’s office. Among the government’s key decision-makers, Vice President Hamilton Mourão – who was a strong influence in reversing Bolsonoaro’s anti-China rhetoric – is said to have the most sophisticated understanding of the subject and is expected to have a seat at the table when the time comes to decide who will build the country’s 5G network.

But that may take longer than some expect. Alleging technical obstacles, Brazil’s government has repeatedly delayed the publication of its 5G bidding process. In a recent interview with Folha de São Paulo, Science and Technology Minister Marco Pontes said that 5G implementation will not occur in Brazil “before the end of 2021.” That is likely to benefit the United States, allowing the U.S. government more time to find and promote an attractive alternative to Huawei; companies like Ericsson and Nokia are still unable to compete with the Chinese telecommunications giant’s low prices.

Yet the delays also smack of a desire to put off a difficult decision that will leave either the United States or China profoundly disappointed. Such a strategy risks reducing Brazil’s competitiveness in a global economy that will increasingly depend on new technologies that range from autonomous cars and drones to communication and global finance. Brazilian agribusiness is set to benefit tremendously from 5G technology, allowing drones to provide accurate assessments of crop and livestock health, monitor soil nutrient levels, and increase productivity. Cheaper drone technology and artificial intelligence may also help fight illegal deforestation, not to mention offer gains in urban transport or cyber security – a major concern in Brazil given that the country often tops global cyber-crime rankings. In fact, few if any areas of the economy or governance will not be affected by 5G technology.

The best way to navigate these new challenges will be for the Brazilian government and universities to invest in building up expertise that will help more policymakers, companies and civil society gain a better understanding of how technology will affect international politics. In addition, Brazilian policymakers, academics and the private sector will benefit from closely following how other countries, such as India, Indonesia, Germany and the UK, are dealing with the emerging tech war, which is set to transform geopolitics as we know it.