With President Donald Trump threatening to upend the U.S.’ economic relationship with Mexico, Enrique Peña Nieto is looking for new friends. The Mexican president may not have given up hope of mending ties with Washington, but Trump’s arrival has given fresh urgency to Mexico’s search for new sources of foreign investment and new trade partners. That has so far meant a particular focus on Europe and Asia; in a sign of things to come, Mexico on Feb. 1 announced a $212 million deal to assemble Chinese cars in the central state of Hidalgo.

But the new reality facing Mexico also offers an opportunity to rethink ties with Brazil and strengthen a bilateral relationship that has long underperformed. Indeed, signs that the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is in trouble should encourage Brazil to reach out to Mexico for several reasons: In addition to mutual economic benefits, stronger ties would allow the two to work together on devising strategies to tackle regional challenges such as drug and arms trafficking, migration, climate change and corruption. To date, lackluster bilateral ties between Brazil and Mexico have been among the key obstacles to broader regional cooperation on these issues.

Though they are the two leading economies in Latin America, there is a lot that sets Brazil and Mexico apart. While Mexico has embraced U.S.-led economic globalization wholeheartedly, Brazilian elites remain deeply suspicious of opening up to trade, and Brazil is still one of most protectionist members of the G20, a group of the world’s largest economies. When Mexico joined NAFTA and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a club of democratic market economies, Brazilian observers concluded that Mexico had sold out to the North, essentially giving up its Latin American identity.

By contrast, foreign-policymakers in Brazil have articulated far greater ambitions on the international stage, ranging from U.N. Security Council reform to leading global peacekeeping efforts – moves that some Mexican observers quietly think of as exaggerated and overconfident. Under former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Brazil focused its attentions on UNASUR, a South American regional body that excludes Mexico, and pursued an independent leadership role on the continent. When the Mexican government nominated the highly qualified central banker Agustín Carstens to replace Dominique Strauss-Kahn as director of the International Monetary Fund, Brazil did not support his candidacy, even though Brasília had long been one of the loudest critics of rich countries’ continued control of the selection process.

Following former President Dilma Rousseff’s contentious reelection in 2014, something of a fragile consensus has emerged in Brazil that opening up the economy is a prerequisite for initiating the long process of recovery – though José Serra, Brazil’s foreign minister, is still struggling to let go of his protectionist instincts. In 2015, Rousseff met with Peña Nieto in Mexico City, where the two signed agreements aimed at doubling trade volumes by 2025 – yet trade liberalization remains highly selective. Considering Mexico’s current plight and Brazil’s tepid desire to open up, the time is ripe for Brasília to be more ambitious. Though commerce has grown over the past years, and Brazil is Mexico’s number one destination for foreign direct investment in Latin America, neither is among the other’s leading trade partners, and Brazilian investment in Mexico remains remarkably low.

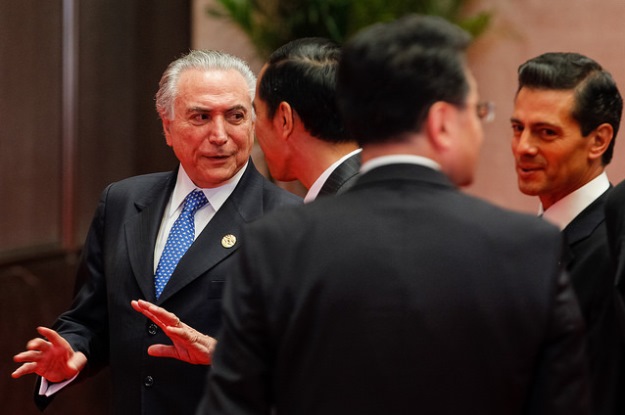

While the current political turmoil in Brazil limits President Michel Temer’s space for maneuver (Temer and his foreign minister may be implicated in Brazil’s widespread and ongoing corruption investigations), he should still try to seize the opportunity and accelerate efforts to sign a free trade agreement between the Mercosur trade bloc and Mexico, and promote a much-needed debate about strengthening Mexico’s ties to South America beyond the existing Pacific Alliance trade group (of which Brazil is not a part). At the same time, Temer should attempt to articulate Brazil’s desire to broaden ties and work together on non-economic issues, including the security-related issues listed above.

Stronger ties between Brazil and Mexico would be in sync with a broader global phenomenon. In a world where the United States will play a far more limited role both economically and politically, new partnerships are emerging, as countries adapt to the deconcentration of power. For example, as Washington’s influence is seen as declining in Asia, ties between India and Japan have prospered. As leaders across the world are scrambling to adapt, a stronger partnership that goes beyond the usual rhetoric between Mexico and Brazil could be Latin America’s best response to the rise of President Trump.