Cuba has just undergone long, brutal days of total blackout. The renewed power outages represent more than just an energy crisis: They’re a sign of a grave systemic crisis. Cuba’s economy, not just the energy sector, is in the midst of its worst collapse, perhaps since independence in 1902.

The current crisis is arguably worse than the calamitous crash of the early 1990s—the so-called Special Period—when the Cuban economy shrank by more than a third over four years. That’s not just because of the depth of the current decline, but also because it’s occuring when the baseline is already low.

Since the 2010s, Cuba has been experiencing consumer goods scarcity, runaway inflation, declining investments, productivity shortfalls, agricultural deficits, falling wages, and, yes, repeated power outages. In addition, poverty and inequality are at an all-time high.

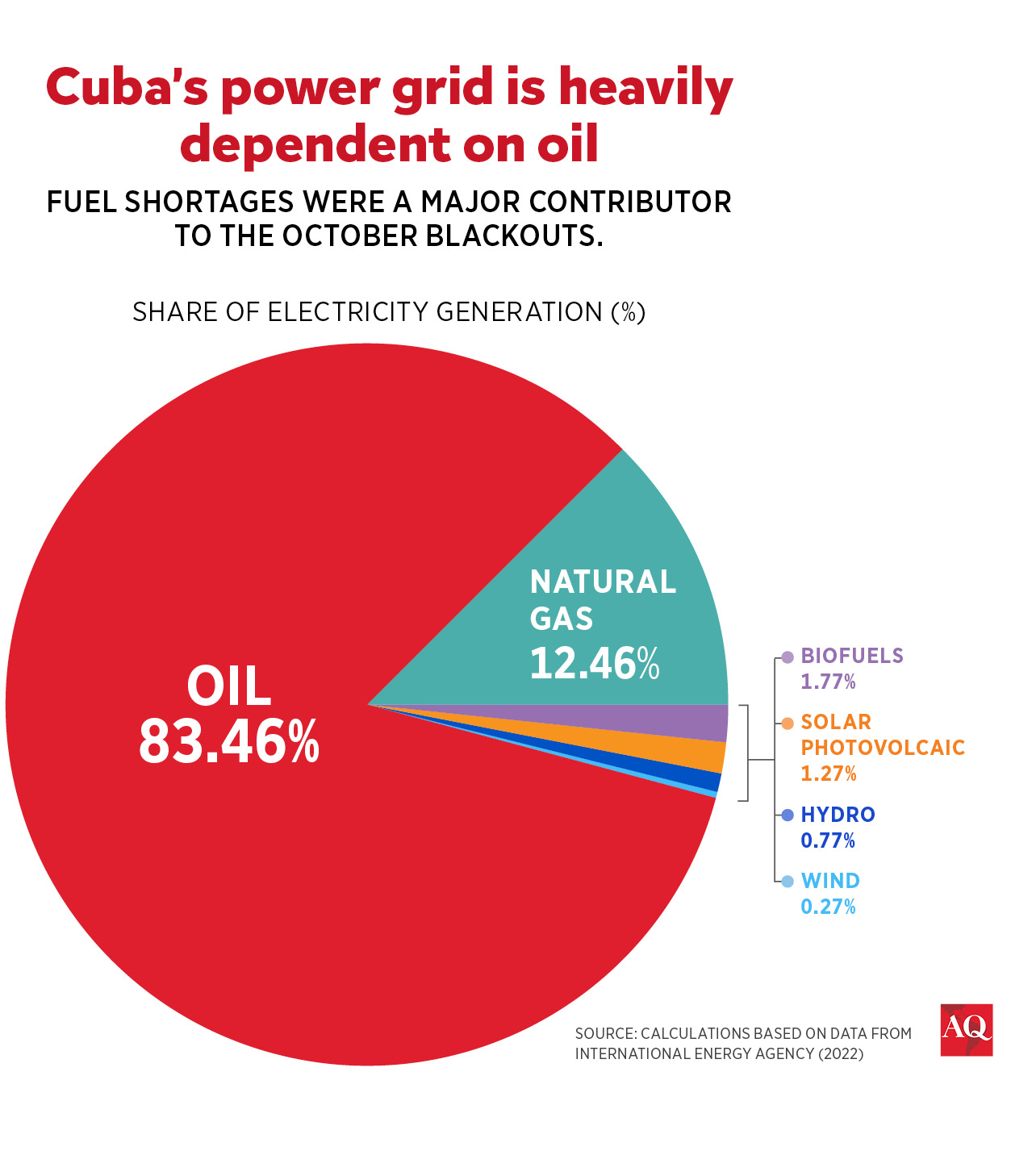

Since at least before the pandemic, Cubans have endured chronic power outages. A typical outage would last approximately eight hours, and they were happening often. Between 2018 and 2022, Cuba’s capacity to generate electricity, never too impressive, fell by almost a quarter. Rather than develop alternatives to hydrocarbon fuels, which Cuba lacks, Cuba has preferred to rely on oil imports. Plant failures began to multiply, exacerbating the outages.

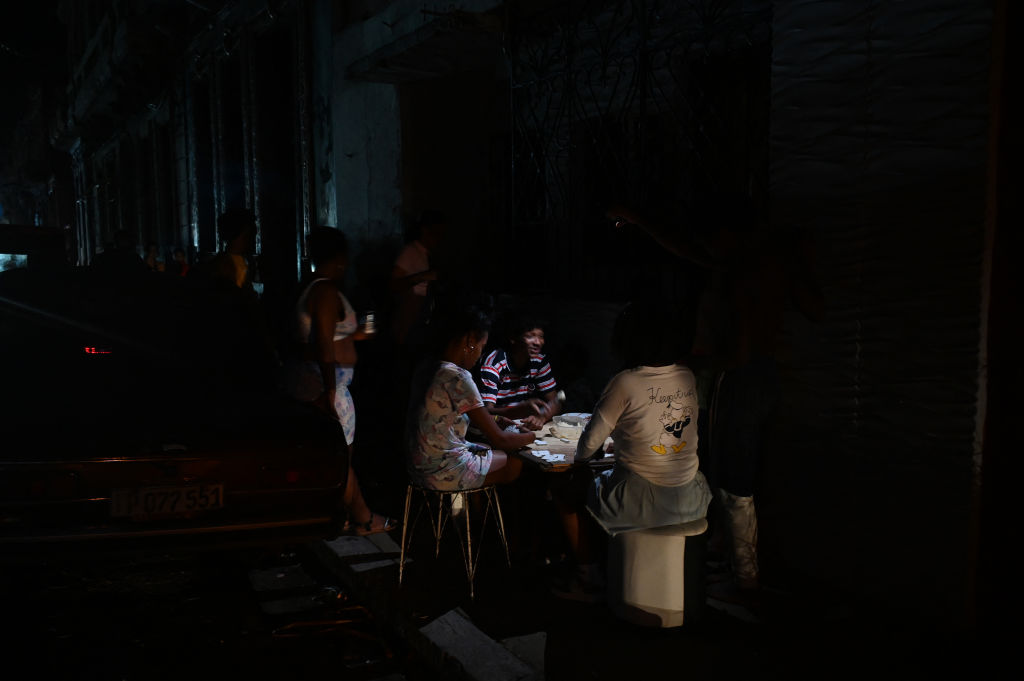

In a sign of desperation, the government in 2022 allowed Cubans to import up to two personal power generators (after paying a 30% tax), which is a big help, but it benefits those who can travel abroad or have overseas visitors. Then came the mid-October energy collapse. For almost four days, the country experienced a series of complete blackouts, and the entire electric grid collapsed at least three consecutive times.

For a country as poor as Cuba, blackouts mean more than just people staying home and enduring brutal heat and humidity. Without power, food spoils quickly. Cooking is impossible without charcoal or wood, both of which are scarce. Many frozen meats become unusable. Water itself becomes scarce and cannot be easily boiled for safe drinking. Disease spreads quickly, and so does crime.

Recovery is not easy. In a country where stores are scarce and famous for their empty shelves, long lines, and unaffordable prices, an empty refrigerator is a catastrophe that cannot be solved quickly and cheaply once power is restored. In short, power outages in poor countries are massive health, economic, and productivity crises.

Root causes

The Cuban government has offered two versions of a root cause explanation. President Miguel Díaz-Canel blamed the U.S. embargo, Cuba’s official explanation for everything that goes wrong. Vice President Manuel Marrero offered a different explanation, blaming “infrastructure deterioration, lack of fuel, and increase in demand.”

Marrero’s explanation is more on target. Cuba’s energy crisis is not caused by the lack of trade opportunities caused by the embargo. Cuba maintains open trade relations with almost every country. In fact, Cuba has enviable trade relations with two of the world’s leading energy giants, Venezuela and Russia, and cordial relations with other local energy producers: Mexico, Brazil, Guyana, and Colombia.

Neither is the issue a blockade of foreign investment led by the U.S. It is true that Donald Trump hardened the embargo, including returning Cuba in January 2021 to the list of “state sponsors of terrorism.” While it seems that some investors in the West hesitate to invest in Cuba for fear of U.S. retaliation, foreign investment still happens, at a pace that the Cuban government is comfortable with. In 2023, the government reported 334 foreign investment projects from 40 countries; 30 new projects were approved that year. Cuba also has allies that could help with infrastructure and care little about upsetting Washington—China in particular.

The payments crisis

The reason Cuba is having problems with its allies is simple: Cuba cannot pay for imports or credits. Its government has no capacity to generate wealth domestically and externally. The country is experiencing an energy crisis because, as Vice-President Marrero says, it is experiencing a resource crisis. Foreign fuel makes its way to Cuban ports, but the Cuban government struggles to generate the money to make payments.

A distortion of the system of property rights is at the heart of the current payments crisis. Since Fidel Castro came to power, Cuba has embraced a system of property rights predicated on the notion that the state alone can generate wealth. Under Castro, the Cuban state spent the 1960s curtailing private property rights to the point of essentially extinguishing private activities. By 1968, the state monopolized trade, investments, production, and most retail services.

For a while after the Cold War, the government liberalized self-employment. But these “liberalized” sectors always came with enormous restrictions. Some of these regulations were relaxed in 2021 to allow small and medium-size firms, but in 2024, new regulations were introduced, including banning the use of foreign currency. Small and medium-size firms face onerous taxation, price controls, and restrictions on access to capital and agricultural activities. Private firms are growing in number, but the goods and services they can trade remain stagnant.

The reason for the stagnation has to do with Cuba’s internal restrictions on property rights. To this day, there are no private banks, investment firms, architecture firms, engineering firms, or law firms. There are no independent courts, so property rights remain insecure. Without these ancillary institutions, private businesses cannot thrive. Cuba’s private sector is more like a gigantic flea market (or food court for tourists) than a generator of wealth and investments.

Cuba’s lack of resource mobilization capacity impairs everything the state does, including generating power. No matter how much Cuba taxes, it fails to generate enough revenue.

Tourism as an issue

The government finds itself in a severe fiscal trap: The state represses supply by restricting the private sector, which keeps growth and tax revenues depressed, forcing the state to engage in declining investments. Prior to the pandemic, investment in infrastructure averaged about 1.5% of gross domestic product, far below the average for Latin America of 2.6%.

State investment is also lopsided. The bulk has been directed toward hotels and tourism, according to a post on X by economist Pedro Monreal. Tourism, a sector of the economy that contributes less than 1% to the GDP, receives more than 35% of investments. This leaves few resources for infrastructure, manufacturing, and agriculture.

Countries generate resources when states and markets complement each other. States provide property rights, independent courts to enforce contracts, inclusive policies, and some collective goods, such as antitrust regulation that protect both competition and consumers. Markets provide the mechanisms for consumers to express demand and for suppliers to meet the demand, but only if property rights are well distributed across society rather than concentrated. This is the argument that earned Daron Acemoglu, James Robinson and Simon Johnson a Nobel prize in economics this year.

Cuba lacks these conditions. Inclusive property rights are missing. In addition, since voters have no chance of electing state officeholders based on political competition, the system lacks any incentives to correct itself. This economic and political calamity, more so than Cuba’s decrepit electric grid, is why the country keeps finding itself in the dark.