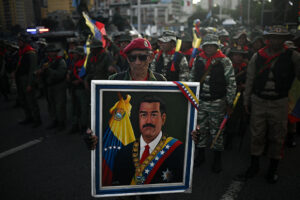

More than a year after the Venezuelan opposition showed receipts that their candidate, Edmundo Gonzalez, defeated Nicolás Maduro at the ballot box, the end of autocracy in Venezuela seems more possible than at any other moment in recent history. The renewed optimism is driven not by changes from within, but by increased U.S. pressure on Maduro, including President Trump’s threat of using military force within Venezuelan territory.

A pressing question now is: How will Venezuela’s military react? The National Bolivarian Armed Forces, or FANB for their initials in Spanish, are the key actors in deciding whether Maduro stays in power – or whether Venezuela sees some kind of leadership transition. While a U.S. military invasion of Venezuela is highly unlikely, a sustained bombing campaign targeting drug boats, and likely extending to strikes inside Venezuela against clandestine airstrips and drug labs, combined with negotiations between Trump administration officials and members of the Venezuelan opposition, could conceivably create fractures within the regime that in turn induce generals to make a change.

It would not be the first time a transition out of authoritarian rule takes place in Latin America. In the region’s great democratizing wave that began in the 1980s, only two dictatorships ended with external military intervention: Manuel Noriega’s rule over Panama which ended with Operation Just Cause in 1989, and Raoul Cédras’s rule over Haiti which ended with Operation Uphold Democracy in 1994. All others ended through actions from inside the country.

In a forthcoming academic study, we looked at the decisive role that Latin American militaries have historically played in both sustaining and dismantling dictatorships. Their mission, structures, and politics change profoundly after transition to democracy. We argue that there are key factors that influence the fate of the military after a transition from an authoritarian regime: the regime type (personalist, party, or military-led) that ties the force to power in different ways; internal dynamics such as cohesion, factions, corruption, and criminal exposure; the mode of transition (negotiated vs. coerced/sudden) that sets the pace and risk of reform; the military’s role in that transition, which affects its leverage afterward; history and political culture, including doctrines and public trust; and the influence of external actors.

In our findings, post-authoritarian governments have generally taken one of four approaches to managing their armed forces. Some abolish the military entirely and replace it with civilian-led security institutions, as seen in Costa Rica and Panama after 1989. Others disband the institution but rebuild from scratch, excluding former personnel—a rare and risky choice exemplified by Iraq in 2003. A third path is to purge selectively, removing those tied to abuses while preserving a professional core, as Argentina did after 1983. In some cases, militaries are handed over intact to new civilian leadership through negotiated transitions and then reformed, as in Brazil (1985) and Chile (1990). Each of these paths reflects a country’s security context, the nature of its transition, and the leverage the military retains as the old regime exits.

Dissolving the armed forces

Following the U.S. invasion that removed Noriega from power, Panama’s new democratic government chose to abolish the military and establish a new security institution, the Fuerza Pública (Public Force). Drawing inspiration from Costa Rica’s demilitarization model and supported by key regional allies, leaders such as Vice President Ricardo Arias Calderón viewed the abolition of the military as essential to stabilizing democracy and preventing future coups. Rather than dismiss all service members, the government restructured existing personnel under a civilian chain of command. A 1994 constitutional reform later formalized the prohibition of a standing army, reaffirming Panama’s commitment to civilian control.

In Iraq, the military was dissolved after the U.S.-led invasion that ended Saddam Hussein’s rule. The Coalition Provisional Authority issued Order Number 2, dissolving Iraq’s armed forces and releasing all personnel from service obligations. Intended to symbolize a complete break from the Ba’athist regime, the decision instead created a massive security vacuum, fueled insurgency, and prolonged instability. The disbandment erased institutional memory, alienated tens of thousands of trained soldiers, and undermined reconstruction efforts. The Iraqi case illustrates the dangers of eliminating a military without a credible plan to rebuild legitimate security structures—especially in countries facing active internal or external threats.

Purge and transitions

Argentina’s military was purged following the country’s democratic transition after the fall of its military junta in 1983. Weakened by defeat in the Falklands War and public outrage over human rights abuses, the armed forces lost their ability to dictate the terms of the transition. President Raúl Alfonsín reduced the military by nearly half, placed it under civilian command, and pursued transitional justice through targeted prosecutions of senior officers while granting amnesty to lower ranks under the “Due Obedience” and “Full Stop” laws. Later reforms separated defense from internal security and abolished conscription to promote professionalism.

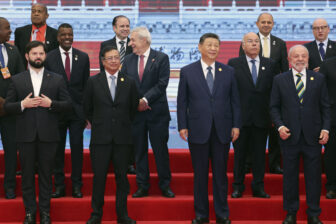

In Brazil and Chile, the militaries were handed over to new democratic governments through negotiated transitions. In Brazil, the 1985 transition was peaceful and consensual, allowing the armed forces to transfer power to civilian leadership while retaining significant autonomy. Over time, constitutional reforms, civilian appointments, and new defense institutions reduced military influence and consolidated democratic control. Similarly, Chile’s 1990 transition followed a negotiated plebiscite that ended Augusto Pinochet’s rule but preserved broad prerogatives for the armed forces under the 1980 Constitution. Pinochet remained army commander for eight years, and early democratic governments faced legal and institutional constraints. Decades of gradual reform and constitutional amendments eventually restored full civilian oversight. Both cases demonstrate that negotiated handovers can secure stable transitions when followed by persistent reform and strong political will to curtail military prerogatives over time.

Much will depend on the role the Venezuelan armed forces play in any transition. If the military plays a dominant role, a “handed-over” institution will likely persist. The armed forces would manage a controlled transition while delaying deeper reforms, as seen in Brazil and Chile. Given the current landscape, this remains the most likely scenario, though the window of opportunity for the FANB to play a pivotal role could rapidly narrow as their position continues to weaken.

If the military plays a limited or subordinate role in a transition driven by democratic forces, it will have little leverage to shape post-authoritarian institutions, and a selective purge—similar to Argentina’s after 1983—could follow. This outcome is less likely, as democratic resistance has so far failed to displace the regime. However, should the FANB fracture and violence erupt, a broader purge and institutional rebuilding under democratic leadership would become more plausible.

A U.S. invasion and prolonged presence could conceivably lead to the institution’s disbandment, as in Iraq, though such a scenario remains highly improbable. Even less likely is a transition that abolishes the FANB altogether. Venezuela’s vast resources, regional security challenges, and entrenched power structures will almost certainly justify retaining a conventional military under new democratic control.

There could also be a scenario combining elements of the above, in which partial reforms accompany a negotiated transition that neither fully dismantles nor preserves the existing military structure. In such a hybrid outcome, Venezuela’s new leaders would likely pursue gradual demilitarization and professionalization while balancing the need for stability, accountability, and civilian control, an approach that could define the country’s democratic trajectory for decades to come.

Venezuela can draw on the region’s proven models to chart a new course—one that reimagines the armed forces as democratic, professional, and mission-focused—grounded in a Latin America that remains largely free of war.