Every presidential candidate pledges, as Mitt Romney recently did, to do more to “focus on Latin America” and “take advantage” of the “huge opportunities” there. It’s been a long time since one followed through. Even by the standards of campaign promises, this one has become so empty that it hardly registers.

It’s not that candidates don’t mean it. The problem is that the dominant issues in U.S.-Latin American relations—immigration, drugs, Cuba, and trade—are also some of the thorniest, most polarizing issues in U.S. domestic politics. The domestic politics have always—and inevitably—won out, and the campaign promises have fallen by the wayside.

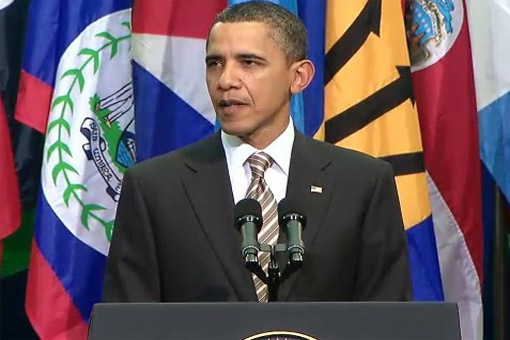

That may finally change. Last month’s election marked a shift in those domestic politics. For the first time in decades, there is reason to expect progress on each of these four issues over the next four years. That progress will come almost entirely for domestic reasons. But it will create an opportunity for a renaissance in the U.S.-Latin American relationship—an opportunity that, if capitalized on, will bring considerable economic and strategic benefits in its own right.

The tragedy of U.S.-Latin American relations since the end of the Cold War is that the things Latin Americans care about most are the things that foreign-focused policymakers control least. Latin American leaders may scream, often with good reason, about the embargo on Cuba, immigration crackdowns, “buy American” clauses, or the havoc the U.S. drug market is wreaking on their societies. But when it comes to each of these, U.S. leaders have their own political interests at stake, and those interests have generally overridden any objections coming from the south. What really needs to be done to improve hemispheric relations is so domestically fraught that the foreign-policy benefits are dismissed as not powerful enough to warrant the political risk.

The consequence has been drift and frequent dissension in our relationships with our closest neighbors. Foreign-policy analysts can (and do) lament this, but the political constraints are a reality of diplomacy in a democracy. Fortunately, the 2012 presidential election pointed to a new convergence of U.S. politics at home and its interests in the rest of the hemisphere.

In his election-night victory speech, immigration reform was one of very few second-term policies that President Obama explicitly pledged to pursue. Republican leaders had already started bemoaning their party’s dismal performance among Latinos in an election when they accounted for a record 10 percent of voters. Romney had never recovered from his primary-season pandering about “self-deportation,” while Obama was riding a wave of enthusiasm over his decision to give young undocumented migrants a reprieve from deportation. The Republicans’ stance on immigration, according to analysis within the party and without, may have cost Romney the election. By the end of election week, House Speaker John Boehner was sending signals that he was ready to work with the White House on comprehensive reform.

The election also marked a change when it comes to Cuba, demonstrating that Republicans have lost their longstanding grip on Cuban-Americans and that a harder line on Cuba is no longer key to winning Florida. Even after taking steps toward engaging Cuba and loosening the U.S.’ Cold War-era policy, President Obama received half or more of Cuban-American votes in Florida, according to exit polls—doubling what Al Gore earned in 2000. In Miami, a Cuban-American congressional candidate who supports change in policy toward the island beat a hardline Republican incumbent. Many Cuban-Americans have quietly welcomed Obama’s more moderate stance. When it comes to the most important change the administration has made—allowing Cuban-Americans to more easily visit the island and support family and friends there—they are voting with their feet, traveling to Cuba in large numbers and flooding it with remittances, cell phones, consumer goods, and much else. Cuba is no longer a third rail in Florida politics, and that opens the way for substantial reform of a perversely outdated and counterproductive policy.

The change in drug policy is coming from the bottom more than the top, but it’s coming just the same. Voters in Colorado and Washington embraced de facto legalization of marijuana, and more than a dozen other states have medical marijuana policies that often mean de facto decriminalization. That reverses what was long seen as an iron law of domestic politics: voters support harsh drug policies and punish politicians who advocate alternate approaches. Since the 1980s, that law has meant the endless prosecution of a drug war fought most violently in Latin America. As Latin American governments, struggling with persistent violence and increasing addiction among their own populations, have begun to advocate more liberal and less militarized approaches to drug policy, U.S. citizens increasingly agree. (It is also worth noting that many more Americans now die abusing pharmaceuticals manufactured in U.S. plants than cocaine and heroin smuggled from abroad.)

Finally, trade played a less prominent role in the campaign, but there was cause for optimism. First, the focus on deficits means continuing cuts to subsidies—traditionally a barrier to deepened trade relations with Latin America, especially its biggest economy, Brazil. A trade agreement remains fanciful, if only because Brazil itself has no interest, but reduced subsidies would allow progress in key sectors such as energy. Second, the looming presence of China has given new impetus to promoting trade in the Pacific, a strategic rationale big enough to supersede domestic political concerns. Aside from Brazil, Latin America’s biggest and most dynamic economies are on the Pacific Rim, and our relationships with them will benefit considerably from the larger push to promote U.S. trade in the region. As Latin Americanists never tire of pointing out, the United States sells much more around the Western Hemisphere—more than 40 percent of U.S. exports—than to the Asian countries that get all the attention from CEOs and policymakers.

There are of course plenty of reasons to want a stronger relationship with Latin America. Thanks to good economic management, the region has enjoyed mostly steady performance through the financial crisis—leading to such strange occurrences as a Mexican president-elect going to Spain and telling the former colonial power, in the midst of economic collapse, that Mexico is happy to help. Latin America is home to booming middle classes that represent big new markets for U.S. businesses. It is full of emerging powers eager to play a global role that will, more than often not, advance causes and values that the United States supports. It is more important to our energy security than any other part of the world—6 of the U.S.’ top 11 sources of oil imports are in the hemisphere, to say nothing of green-energy and natural-gas resources—and represents, in the energy analyst Daniel Yergin’s words, a new center of gravity in global energy markets.

Those interests have existed for a while. What changed last month was the apparent insurmountability of the domestic obstacles to advancing them. On immigration, Cuba, drug policy, and trade, U.S. politics are undergoing a transformation. That means an opportunity for a golden moment in the U.S.-Latin American relationship, just when everyone had written off those campaign promises for good.