This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on the Trump Doctrine

PARAMARIBO—Suriname’s first female president, Jennifer Geerlings-Simons, is leading the world’s most forested country. She’s also set to oversee the world’s latest oil boom.

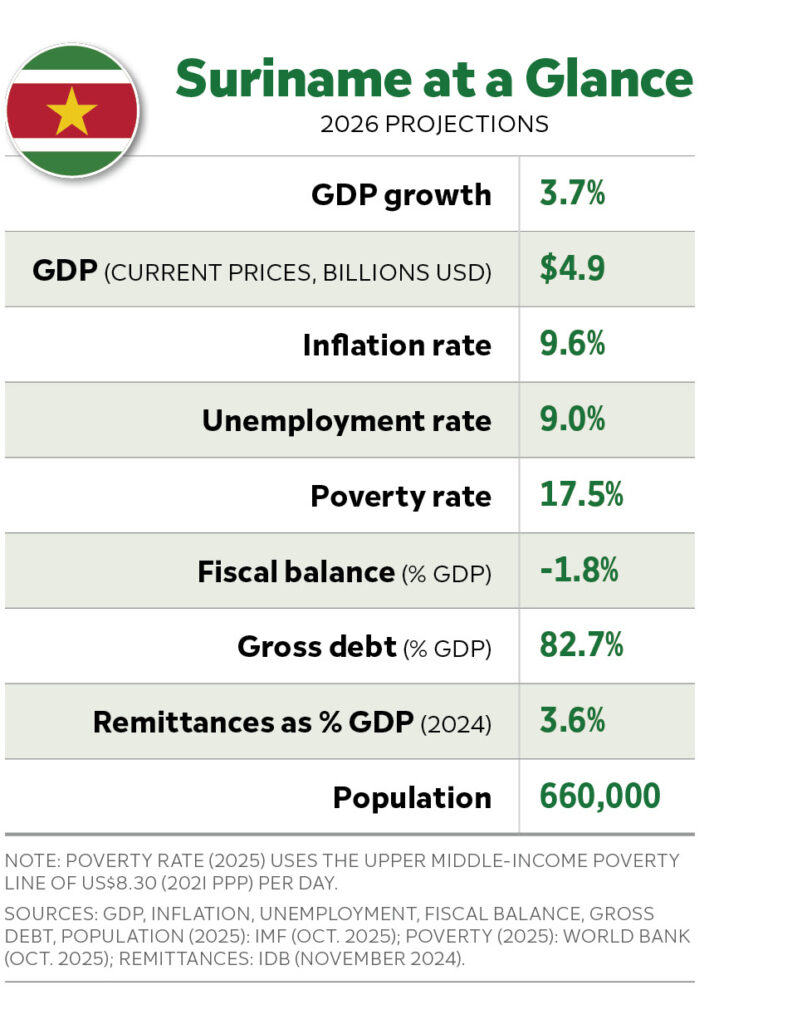

The Dutch-speaking country of some 660,000 people is about to experience an oil bonanza that could double its $4.7 billion GDP by 2030.

But last July, after winning the National Assembly’s endorsement, Geerlings-Simons took the helm of a country in crisis. A still-developing parliamentary democracy in which the president is elected indirectly, Suriname’s well-documented struggles with corruption and governance issues have raised questions about how it will deal with its oil windfall. The country’s citizens are exhausted after years of high inflation and austerity measures that sparked massive protests in 2023, yet also helped bring the country back from the brink of bankruptcy.

“The problems of the country are enormous,” Geerlings-Simons told AQ in a recent interview in the nation’s capital. “If we don’t prepare properly, we will inevitably suffer a resource curse,” she said, referring to the condition also known as the “paradox of plenty,” in which resource-rich countries fail to secure lasting and full benefits from their natural wealth. To right the ship of state and prepare for the upcoming oil windfall, her administration is betting on education, economic diversification, and governance reforms.

In many ways, Suriname seems to be on the same development track—and facing similar challenges—as its neighbor Guyana, which began ramping up oil production from the same geological offshore basin a few years earlier. Guyana has been among the world’s fastest-growing economies since 2020, yet the poverty rate remains high, at around 58%, and health outcomes still lag behind regional and peer-country averages, according to the World Bank. Both Suriname and Guyana are eagerly watched by investors, as well as development economists around the world, to see whether the bonanza will buoy or sink their countries.

In the case of Suriname, growth in the former Dutch colony has stabilized since the COVID-19 pandemic at around 2.5% to 3% annually, and the poverty rate is relatively low, with about 17.5% of the population living below the upper-middle-income poverty line. Yet the main challenge Suriname faces at this “critical juncture,” the IMF recently stated, lies with its institutions. “At the eve of a significant oil boom, the authorities’ task is to act now to lay the groundwork and build the institutions needed to fully harness the country’s newly found oil wealth,” the multilateral lender argued in a November 2025 country report. The World Bank holds a similar view: “It will be crucial to strengthen governance institutions and enhance human capital” to minimize the risks associated with an over-reliance on the oil industry.

Geerlings-Simons, who turned 72 last year, acknowledges that setting the country on a path to success will be a long, complicated process. “I can’t turn a mud puddle into a glass of water in just one step,” she told AQ.

Until now, Suriname has relied on modest onshore crude production of around 16,000 barrels per day, which generated $722 million in gross revenue for the state-owned oil company Staatsolie in 2023. But a new era began after France’s TotalEnergies and the U.S.-based APA Corporation made a massive offshore oil discovery in 2020. Now, the companies aim to produce as many as 220,000 barrels of oil per day by 2028 through the GranMorgu project, a $10.5 billion investment that marks the country’s first foray into deepwater production. The project, about 150 kilometers out to sea, has catapulted Suriname to prominence as the new frontier of global energy.

A difficult inheritance

Institutionally, the country is still shaking off the shadow of former President Desi Bouterse, the dominant force in Suriname’s politics since independence from the Netherlands in 1975. He led a military coup in 1980, became the country’s de facto ruler through 1988, and continued to pull strings, winning two terms as president from 2010 to 2020 that were marred by corruption allegations and an economic collapse. He was convicted in a Dutch court of drug trafficking in 1999, and was handed a 20-year sentence in Suriname in 2019 for executing 15 political opponents in the 1980s. He died in hiding in the country’s deep jungles in 2024.

Geerlings-Simons, a medical doctor, witnessed those events firsthand. She has been active in politics since 1996, when she was elected to Suriname’s unicameral parliament after joining Bouterse’s National Democratic Party (NDP), attracted by its rhetorical focus on social equity. She later served as president of the legislature from 2010 to 2020, resigning her seat after the NDP lost the 2020 elections. During this time, she said, she grew close to Bouterse and spoke to him often on both political and personal matters.

“Because I was not in the administration myself,” she told AQ, “I was able to observe what went right and wrong with all those governments.”

On the campaign trail in 2024, she was pragmatic and direct. She favored some of the austerity measures that had caused public uproar under her predecessor, Chandripersad Santokhi, but earned broad support in large part for her longstanding commitment to universal health care and education.

Though her politics lean left-populist, as a speaker she is subdued and matter-of-fact. Geerlings-Simons gives the impression of a strict aunt keeping a close and critical eye on the family—her supporters affectionately call her “Aunt Jenny.” Backers hope her extensive political experience will help her prepare the country for the changes ahead.

Her first major test was whether she could form a governing coalition after her NDP party won 18 of 51 seats in parliament last July. She passed the test quickly, securing a two-thirds coalition thanks largely to her reputation for pragmatism. The only bloc to refuse was that of outgoing President Santokhi; even the National Party of Suriname (NPS), historically a fierce opponent of the NDP, joined her effort.

One key element that will set her administration apart, Geerlings-Simons said, is a zero-tolerance policy toward corruption. “Anyone who deliberately wants to benefit themselves will have to step down when I find out. Because I will not tolerate that.”

Photo by Ranu Abhelakh

The looming boom

Suriname began producing oil in 1982 following the creation of Staatsolie at the outset of military rule. Since then, the national oil company has grown to become the largest and most profitable firm in the country. In May 2025, Staatsolie secured a $1.6 billion loan to invest in GranMorgu alongside the foreign players. It has a 20% stake in the project, which sits atop 760 million barrels of oil and is expected to create more than 6,000 direct and indirect jobs.

Sergio Akiemboto, Geerlings-Simons’ chief of staff and a member of the Staatsolie supervisory board, said the administration is determined to use oil revenue to develop the agriculture sector to boost food production for both the local economy and export to neighbors, while implementing a sweeping education drive.

“Technical education is especially important. We are lagging far behind in this area, and this could mean that many of the high-level technical jobs will be filled by foreigners,” Akiemboto told AQ. “The oil and gas sector is a technical industry … the real benefits will mainly come from local content through the services that need to be provided. We must prepare our entrepreneurs for this,” he said.

Geerlings-Simons doesn’t sugarcoat the challenge. “Our education has deteriorated terribly at all levels,” she told AQ. Both teachers and nurses have left the country in large numbers, mainly to settle in the Netherlands. The president plans to organize a major education conference in the first quarter of the year to formulate a long-term plan to train workforces and small-business operators not only for the oil and gas industry but also the tourism and IT sectors.

The administration’s other focus is transparency and governance. Geerlings-Simons has announced a push to digitize government in 2026, which she considers a crucial step in reducing corruption. She also seeks to invest in the country’s tax authority and establish a sustainable savings and stabilization fund to direct oil revenues into green portfolios and investments abroad.

Akiemboto explained the sense of urgency: “The oil boom will bring many benefits, but as a government we are currently insufficiently organized to cope with it,” he said.

The same urgency comes from the president. “The time we have to prevent a resource curse is very short,” Geerlings-Simons said. “I don’t know if we will be able to prevent it entirely, but we are going to work very hard to at least reduce the risk.”

Pressure to deliver

While Geerlings-Simons’ five-year term has barely begun, some analysts are growing concerned about inaction. Winston Ramautarsing, an economist and consultant in Suriname, worries about the signs from Geerlings-Simons’ initial months in office. “The government is failing to deliver real results. I don’t see any restructuring of the government or privatization of loss-making state-owned companies. That is not good policy,” Ramautarsing told AQ.

He also cited a lack of transparency about her plans in general, and specifically over new debt. In October 2025, the government issued two dollar-denominated bonds maturing in 2030 and 2035 on the international market, raising a combined $1.8 billion, which will be used to refinance outstanding papers.

Steven Debipersad, chairman of the Association of Economists in Suriname (VES), believes it is still too early to evaluate Geerlings-Simons’ government, but said she seems to be setting a good example. “She promised austerity in her election campaign, and we have seen that so far.”

He said he is also impressed by the emphasis Geerlings-Simons has placed on environmental policy. At both the UN General Assembly in September and the COP30 climate summit in Brazil in November, the president spoke powerfully about the opportunities countries like Suriname can pursue through climate financing. With more than 93% forest cover, Suriname seems well-positioned to benefit from recent advances in forest finance, for example.

While Geerlings-Simons faces serious challenges, she has a window of opportunity, given her working coalition in parliament. During her inauguration, she offered an ambitious goal: “I come into this position to serve, and I will use all my knowledge, strength, and dedication to make our wealth available to all our people.” Now, against the backdrop of high expectations and a tumultuous national history, success may depend on how effectively she uses her most valuable limited resource: time.