The ongoing clash with the Trump administration over the future of the Panama Canal has made President José Raúl Mulino’s already tough position even more difficult.

Even before Trump’s inauguration, some U.S. officials worried that China had gained the capacity to interfere in canal operations through control of nearby infrastructure and cyberattacks. (Panamanian officials dispute these claims and note that an independent Panamanian body, the Panama Canal Authority, is the sole operator of the canal.) Slow progress on a new reservoir to feed the canal is another source of friction.

However, Trump’s approach to these legitimate concerns has been to publicly blast Panama’s canal management and make extreme demands, like a handover. This approach misses a fundamental point: Mulino needs political capital to deliver on U.S. priorities—whether that’s reducing Chinese control over strategic infrastructure, closer partnership on canal security, or quick progress on a new reservoir.

For domestic political reasons, Mulino’s room to maneuver is already tight. The Trump administration should be wary of further weakening him. If Trump instead simply aims to take back the canal, a weak Mulino may be part of the plan. But then there are much greater dangers to consider—for the United States, Panama, and the world. A partially or fully U.S.-controlled canal, if such a thing is even feasible, would not make either the U.S. or international trade safer. It would do the opposite.

A government born weak

Mulino inherited a daunting set of challenges. He won the presidency almost by accident, “with votes that weren’t his,” according to Panamanian political scientist Harry Brown. Campaigning first as the running mate of ex-President Ricardo Martinelli, the latter’s disqualification left Mulino at the top of the ticket. Now, he is effectively a president without a party. Martinelli, who has been living in the Nicaraguan embassy in Panama since February 2024 to dodge an arrest warrant for money laundering, has become a backstage veto-player, of sorts, holding sway within their shared Realizando Metas (RM) party. Besides Panama’s Chamber of Commerce, Mulino has few powerful backers.

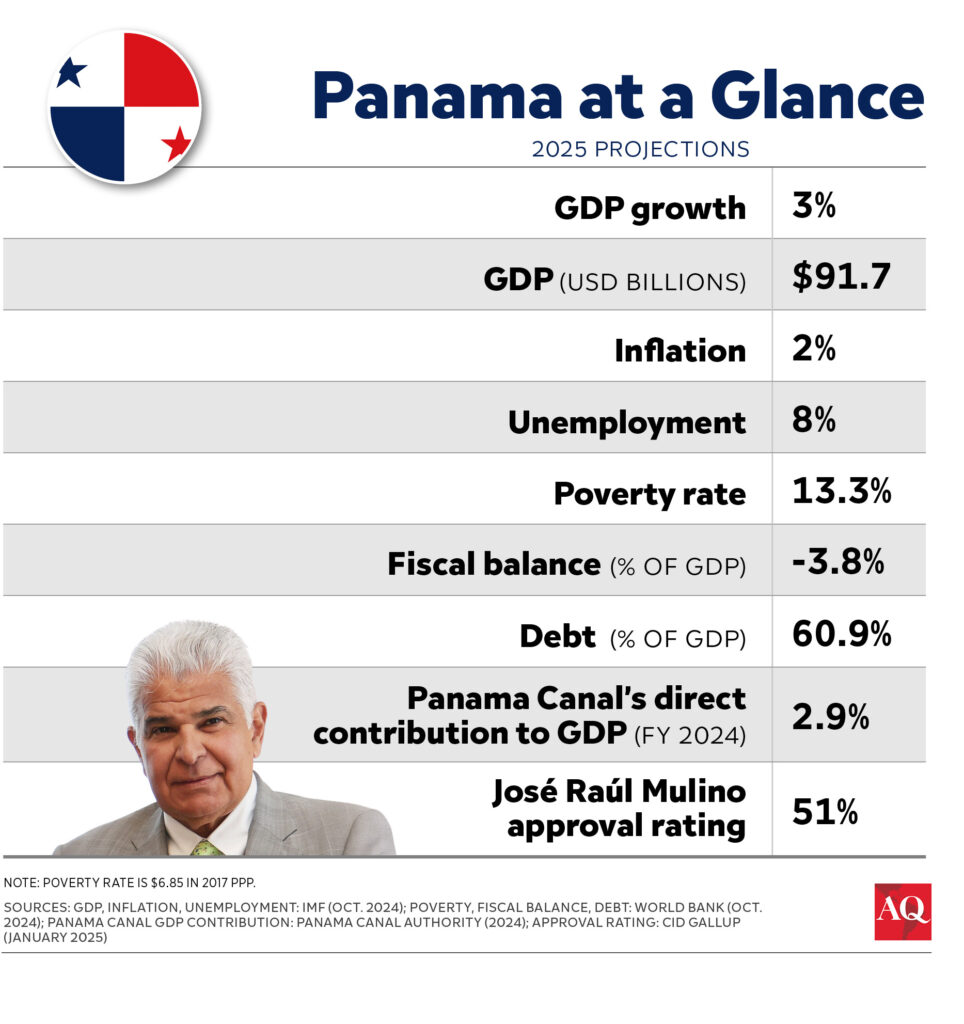

The fact that Mulino nonetheless recently passed a social security reform speaks to his political skill. He’ll need it to face down all his other challenges. There’s Panama’s 7.4% fiscal deficit—the largest in its history, thanks to his predecessors’ spending—the threat of fresh credit rating downgrades like the one Panama suffered last year and the need to address nearly double-digit unemployment without increasing the deficit. There’s the risk of legal challenge and popular pushback if the government moves ahead, as it appears to be doing, with plans to reopen the Cobre Panama copper mine, shuttered by a 2023 Supreme Court ruling amid mass protests. There’s the possibility canal revenues, a third of which go toward financing the government, will decrease if Trump’s tariffs and retaliatory ones diminish global trade flows. And there’s the chance that latent, simmering anger over Panama’s extreme inequality—which endures despite years of fast-paced growth—could once again explode. “Panama is a tinderbox,” Raisa Banfield, a leading Panamanian environmentalist who participated in the 2023 protests, told me.

Mulino’s popularity is tumbling—from 57% approval in January to 29% late last month, according to a recent poll. Government insiders know the honeymoon is over and that Mulino needs every ounce of political capital he has left to advance his priorities, including Rio Indio’s new reservoir, which is vital to the canal’s future.

The risks of public pressure

That’s where Trump comes in. Calculating how to respond to his ever-shifting demands—from lower fees for all U.S. ships to free passage for U.S. warships (in violation of the canal’s governing laws) to greater distancing from China to a handover of the canal itself is a tall order. “It’s distracting Panama and taking up huge amounts of energy,” said one presidential advisor. Meet one or two public asks, as Mulino did after Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s February visit, and he looks pragmatic. Meet each new demand, again and again as they escalate, and he risks looking weak, even manipulable. “There’s a fine line between being a puppet and partner,” one Foreign Ministry official told me.

Mulino might move faster to curb Chinese presence if he didn’t have to worry about it looking like the U.S. was forcing his hand. China had already lost ground in Panama before Trump began making extreme demands. Conventional, often quiet diplomacy during his first term and Biden’s produced results: dismantling a Chinese video-surveillance system and scuttling plans for a Chinese cross-country train. Now, a U.S. company is doing a viability study for the new railroad project. A Panamanian audit may end a Hong Kong-based company’s lease of two ports near the canal, and joint military training with the U.S. is in the works.

There may be more Mulino can do to reassure the U.S. and mark distance with China—for instance, increase cyber security cooperation, set up a canal security interagency task force within the Panamanian government, or exchange representative offices with Taiwan. The U.S. has valid outstanding concerns: Huawei’s presence, the Chinese share of First Quantum’s copper mine, and the fourth bridge over the canal—under construction by a Chinese company after no U.S. firms bid on it. But Mulino isn’t acting in a vacuum. Move on any or all of these fronts, and he will likely face pushback from Panamanian elites with business interests tied to China—not to mention China itself. And as long as Trump continues talking about “taking back” the canal, Mulino may be wary of burning his bridges to Beijing entirely.

Territorial ambitions

What if Trump really means it when he says, “We’re taking it back”? While many argue it would take an invasion—Mulino has ruled out a handover—the U.S. has huge leverage. “If Canada and Greenland both fail,” said analyst Alonso Illueca, referring to Trump’s other territorial expansion projects, “and you need a win with zero casualties, there’s Panama.”

Hypothetically, Trump could starve the Panamanian financial system of U.S. dollars (as the U. S. did prior to the 1989 invasion), cancel visas, and sanction trade through the canal. Logistically, the U.S. could not run the canal without its highly trained Panamanian boat pilots and workforce. But it’s an open question whether Panama, under extreme pressure, could be forced into accepting a measure of U.S. presence and oversight: for instance, a semi-permanent U.S. military presence in or around the canal (despite the prohibition against permanent basing rights in the neutrality treaty protocol) or some type of U.S.-run advisory structure atop the canal authority.

A takeback or something like it wouldn’t make the canal any safer. Far from an act of selfless altruism by late President Jimmy Carter, as Trump often portrays it, the decision to give Panama control of the canal was motivated by the cold-eyed realism of Henry Kissinger. He understood that, even flanked by U.S. military bases, such a fragile piece of infrastructure would always be vulnerable to sabotage. Neutrality was and remains its best source of protection.

As long as the U.S., China, and other countries need the canal to function, they have little incentive to sabotage it. Place it under U.S. control or something akin to it and that calculus could change. The canal’s geography and water sources mean it will always be vulnerable to interference. Taking it back would amplify those risks, not reduce them.

The Panamanian government appreciates U.S. concerns—but Mulino may not be able to do much about them if sufficiently weakened. There are paths out of the current impasse, but pushing harder doesn’t make them more likely. Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s April 7 visit to Panama could, and should, be a chance to pursue a new, more pragmatic approach.