Haiti’s President Jovenel Moïse was assassinated in the early hours of July 7.

After announcing Moïse’s assasination, Claude Joseph, the acting prime minister since April, claimed he was in charge. Moïse had named a new prime minister on Monday to formally replace Joseph, but he had not been sworn in, sowing confusion over Joseph’s claim to power.

Further adding to the confusion around the line of succession is the fact that the president of the Supreme Court died of COVID-19 last month. There has also been no sitting parliament since Moïse dissolved the body in January 2020.

AQ asked experts on Haiti to share their reactions to these events.

Monique Clesca, Haitian journalist, international development consultant and retired UN official:

Today in Haiti, people are in lockdown. There is no noise whatsoever. I haven’t heard one motorcycle this morning. We are afraid of the unknown, but it’s more than that. It’s fear of the different possibilities of who might be behind this – an international drug kingpin, a gang leader? This is a nightmare situation for us. Whoever did this has a lot of money and a lot of power.

It’s not clear if Claude Joseph holds power or if he has a power base. A journalist he is friends with was killed just last week. So nothing is clear, and a country that was in chaos before is now more chaotic. Joseph declared a state of siege, but we were already in a state of siege. In fact, this crisis has gone on for three years, and we have been warning that we could get into a scenario in which nothing is under control. But our voices were not heard. The international community instead chose to side with an autocrat. They accompanied this man, so they bear a responsibility in what is going on now.

Last week, 20 people were killed in one neighborhood in one night. Where was Joe Biden? Where was Boris Johnson? Where were they when we were being killed? I don’t want crocodile tears now from the leaders of the world. They are part of the problem because they have done nothing.

Wherever we go next, the solution must be a Haitian solution. We need someone to rise up and tell people to keep calm. This is a moment where we need to come together. Eventually, this can be an opportunity to transcend and transform.

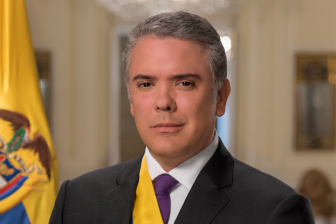

Eduardo Gamarra, Latin American politics and democratization professor at Florida International University:

I knew the president well. He had given a guest lecture to my class, and my students got to know him as well, so this hits home. You study politics and policy, but when dramatic things happen you really understand the consequences of political breakdown.

Haiti’s situation can be described as beyond anarchy now. Right now no one is in charge except the gangs that are terrorizing everyone. A month ago a group of Haitian politicians told me of the severity of the situation, and that there were many plots against the president’s life. They also explained the way in which the gangs had just become so absolutely enmeshed with politics: You have drug traffickers linked to politicians and to former police officers and even businesspeople opposed to the president that have been financing these gangs.

Trying to put the country back together seems insurmountable. Even after the hurricane there was a semblance of governance, but there is none now. There are no armed forces or police forces that can control the violence.

The international community, and the U.S. need to play a significant role now – beyond statements of grief and support. The team looking at the Caribbean within the administration needs to look at the broader consequences of what is happening there because it will spill over. The Dominican Republic is already militarizing the border.

Everyone is always asking why Haiti and DR have had such different outcomes. I’ve advised both DR and Haiti governments for many years, and having lived in both countries, I say they really have a very different political culture and institutions. The international community, further, has not been helpful to Haiti. We help them, then we forget them.