PANAMA CITY — President José Raul Mulino took office July 1, promising significant action on crucial trade and foreign policy fronts. Analysts said he’ll likely take decisive measures on the migration crisis in the Darién Gap and the Panama Canal’s critical water shortage, while the fate of the largest copper mine in Central America closed last year remains uncertain.

In the hours after his inauguration, Mulino signed a memorandum of understanding with the U.S. to “close” the Darién Gap on the border with Colombia to stop migrants from crossing. In a strong show of support for the move, the U.S. delegation was led by Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas.

“The number of illegal immigrants passing through the Darién is shocking. What’s more, international criminals use this region as a base of operations,” Mulino said in his first speech as president. “I’ll look for solutions with the countries involved, especially with the U.S., which is the final destination of these immigrants.” A former security minister, Mulino, 65, was ex-President Ricardo Martinelli’s running mate until Martinelli was disqualified by the courts over a money laundering conviction.

More than half a million people transited the inhospitable Darién jungle in 2023. Most sought government assistance at Bajo Chiquito, the first Panamanian immigration reception station, and authorities bused them through the country to the border with Costa Rica, where they continued their journey north. Now, Mulino is set to end this policy of facilitating transit. Panama has spent about $200 million attending to migrants, so repatriating them is “unaffordable” without help, the president said in an interview days ago. He expects U.S. support for repatriating or deporting migrants and reiterated his view that the U.S. southern border lies not in Texas but instead in the province of Darién.

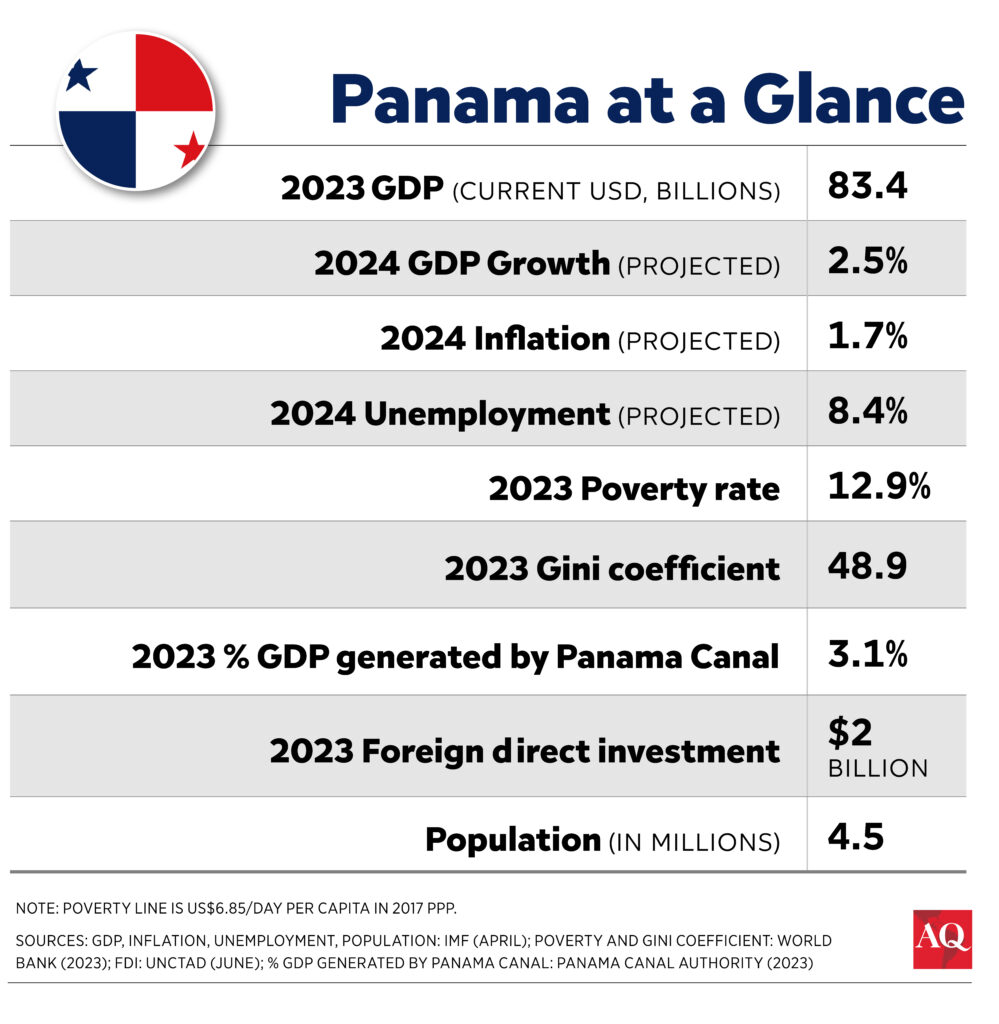

Panama’s economy outperformed most of its regional peers last year with 7.3% growth, exceeding expectations for the third year since 2020. However, Mulino’s administration will face significant challenges as economic activity is “expected to slow and the outlook is uncertain,” the International Monetary Fund acknowledged last week. While the fiscal deficit has declined from 10% of GDP in 2020 to only 3% in 2023, private consumption is still below pre-pandemic levels, and unemployment is higher than in 2019 and set to rise to 8.4% this year. “Key risks include the loss of investment grade, further social unrest, the fallout from the end of copper production (including from international arbitration proceedings), and external risks,” the IMF said in a statement. For 2024, the multilateral lender projects 2.5% GDP growth.

Given this likely slowdown, Mulino can ill-afford to fail to deliver on major campaign issues like migration. Greater enforcement at the Darién and the end of busing will likely reduce migration but could open Mulino to a different political risk: that migrants may try to evade authorities and remain in Panama instead of continuing north to the U.S., political analyst José Eugenio Stoute told AQ. Panama’s relative economic strength may make it an attractive destination to migrants who may consider Panama a more realistic destination due to increased deterrence and concomitant costs throughout Central America and Mexico.

To “close” the border, Mulino has to engage diplomatically with various other countries. Without an international treaty that spells out what to do with migrants arriving at the Darién, the government will have its hands tied, said analyst and former diplomat Julio Yao. “It’s not just a question of paying the costs of repatriation,” he told AQ. “The U.S., Colombia, and Panama can’t just make their agreements that affect the many other nationalities that arrive at the Darién Gap whose human rights must be respected,” Yao added.

Panama’s need to be heard on the international stage will coincide with its seat as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council for the 2025-26 term. This will be a major opportunity but also a challenge for Mulino’s government, said Alonso Illueca, an international law professor at the Santa María La Antigua University in Panama. The administration needs to show it can garner international support on solutions for the Darién and also avoid a humanitarian catastrophe, which it may be able to do “if Panama achieves a consensus among the members of the Council that the situation constitutes a threat to peace and international security,” Illueca told AQ.

Mulino seems willing to wade assertively into hemispheric politics. On Venezuela, for example, he has been more combative than most of the region’s leaders, promising not to recognize the results of the July 28 elections if there’s evidence of fraud.

Water shortage and “the” copper mine

Panama’s other major challenge of global significance is to address the water shortage that has reduced traffic through the Panama Canal, transited by an estimated 3% of the world’s annual trade. Last November, in an unprecedented decision, the Canal restricted the monthly number of passages from 38 to 22 and reduced the maximum size of ships. The problem of the Canal’s water shortages “has been kicked from government to government,” said economist Raul Moreira. “This created chaos in global trade as all these ships started heading towards the Suez Canal but were attacked in the Red Sea,” he told AQ.

“We’ll revive [the Canal] well, make it more efficient, and have more ships will cross our isthmus,” Mulino said in his inaugural speech. He promised to push through a massive damming project on the Río Indio, which would shore up the Canal’s water supply and preserve its annual revenues, which reached almost $5 billion last year. However, the project has encountered resistance from groups concerned about environmental harm and reduced access to water in nearby communities.

The project will likely get underway over the coming year, but Panama’s other major economic question, the future of the Cobre Panamá copper mine, remains uncertain. “It is one of the great mysteries of this administration,” Stoute told AQ.

The revenue from the mine, operated by Canadian company First Quantum Minerals (FQM), was equivalent to around 4% of the country’s GDP before it was shuttered last year following massive protests and Supreme Court decisions that invalidated its contract. Panama is on the hook to pay FQM hundreds of millions of dollars in arbitration, and Mulino has floated the idea of reopening the mine for long enough to pay down this debt and then close it in a way that does not penalize Panama financially.

“We have to keep an eye on Mulino’s ‘open to close’ proposal,” said Moreira. He added that the concrete details of such a proposal are critical, especially because the abrupt closure of such a massive open pit operation in the middle of an ecological preserve could cause more environmental damage than it prevents. Regardless, Mulino has said he will not negotiate until FQM withdraws the two international arbitrations it has opened against Panama.

“The situation regarding the copper mine is extremely complex,” Illueca told AQ. The administration must balance the threat of arbitration, a new moratorium law on metallic mining, and two Supreme Court rulings declaring the Cobre Panamá mine unconstitutional. All this “greatly limits” the new administration, Illueca said.