Odilon de Oliveira is 68 years old and worried about retirement – but not for the reasons you think. One of Brazil’s most outspoken criminal judges, de Oliveira has sent dozens of the country’s most wanted drug traffickers to prison for extended stays. But that work has come at a cost – he and his family are the targets of frequent death threats, and the PCC, a Brazilian drug-trafficking organization, reportedly has a $300,000 bounty on his head.

Those threats mean the judge is reliant on bodyguards to guarantee his safety – a state-sponsored security detail that, when he retires, will no longer be by his side. De Oliveira recently told Brazilian newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo that if the security was removed, he would be forced to flee the country. “I’m a hostage to the robe,” he said.

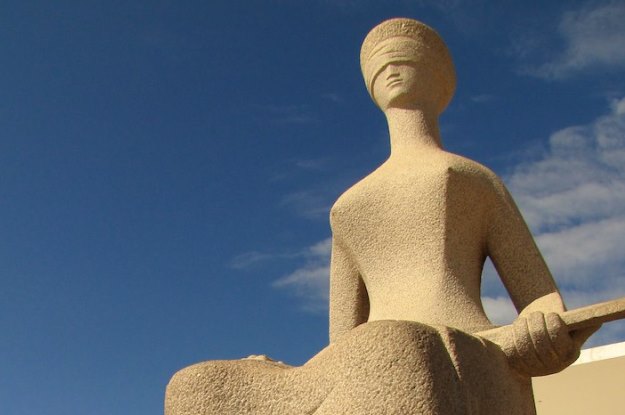

The risk of being a judge in Latin America isn’t limited to Brazil. From Mexico to Venezuela and even Uruguay, it’s not uncommon for judges and states’ attorneys to confront interests that are determined to stop them from carrying out their work – through violence if necessary. Despite the possibility of political persecution or physical harm, courageous judges throughout the region continue to fight against efforts to derail justice and dilute judicial independence. Much like the Top 5 “Corruption Busters” AQ featured in 2016, these regional leaders are part of a historic shift in Latin America toward more accountability and transparency in business, politics and the rule of law. In addition to de Oliveira, here are four more current and former judges whose stories are worth noting:

Julia Staricco, 41, is a federal judge from Uruguay who has presided over countless investigations into gang activity and overseen some of the country’s biggest corruption cases. Though Uruguay is ranked as having the strongest rule of law in the region, according to the World Justice Project, there are still those willing to resort to violent means to disrupt criminal investigations. In 2014, Staricco’s home was attacked and her bodyguard shot at by presumed members of a drug gang that had previously sent her a death threat. Staricco is now overseeing investigations into Commando Barneix, a group of ex-military members that has said it would “avenge” the 2015 suicide of Pedro Barneix, a former general who took his own life after being found guilty of political homicide for the 1974 murder of a local politician. The group has already sent death threats to a handful of Uruguay’s most well-known judges and state’s attorneys, including Attorney General Jorge Díaz.

Miguel Ángel Gálvez has presided over many of Guatemala’s biggest criminal cases, from high-profile charges against drug traffickers to a war crimes case against former army general and President Efraín Ríos Montt. He has also sent two ex-governors to prison on corruption charges. For his efforts, Gálvez was named the 2016 Person of the Year by Guatemalan newspaper Prensa Libre – but this type of recognition has also made him a target. The 54-year-old judge has received threats and messages of intimidation throughout his career, some of those related to the so-called TCQ corruption case that led to the 2016 arrest and detention of former President Otto Pérez Molina and his vice-president, Roxana Baldetti. Gálvez’s response to the high-profile caseload? “I’m just doing my job.”

Karla Moreno was a criminal judge in Venezuela until Feb. 20, when she quit in the middle of a case against three journalists who had photographed a march in support of jailed opposition leader Leopoldo López. Officials from Venezuela’s state intelligence agency (SEBIN) pressured Moreno to send the journalists to jail; Moreno didn’t think they had committed a crime and refused. The judge’s decision to step down publically was bold, particularly given that in today’s Venezuela she could have easily been sent to jail herself. In December 2009, former President Hugo Chávez jailed judge María Lourdes Afiuni after she provided conditional release – against the will of the government – to a businessman who had been charged with evading currency controls. Afiuni was sentenced to house arrest in 2011 and released from prison two years later, but to this day is barred from practicing law in the country.

Luis María Aguilar Morales, 67, has been the president of Mexico’s Supreme Court since 2015. While under consideration for the post, Aguilar presented a four-year judicial development plan aimed at better protecting human rights, ensuring an ongoing reform to the country’s penal system, and improving the judiciary’s track record in corruption cases. He has also emphasized the need to look closely at lawmakers, lawyers and politicians to avoid corruption. In 2016, he spoke out forcefully on the need for the government to protect federal and local judges from threats and violence after the killing of Vicente Bermúdez Zacarías, a federal judge who had presided over cases against drug-trafficking kingpins including Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán. Upon assuming the post, Aguilar signaled his intention to take on criminal groups, stating in his four-year plan that the judiciary had a “great responsibility to act without fear.”

—

Russell is a senior editor and Krygier is an editorial intern with Americas Quarterly.