In the wee hours of November 17, 1901, police raided a private house party in Mexico City’s central Tabacalera neighborhood. Beyond the standard revelry, what the raid uncovered would scandalize the city and realign notions of sexuality, gender and class in Mexico for generations.

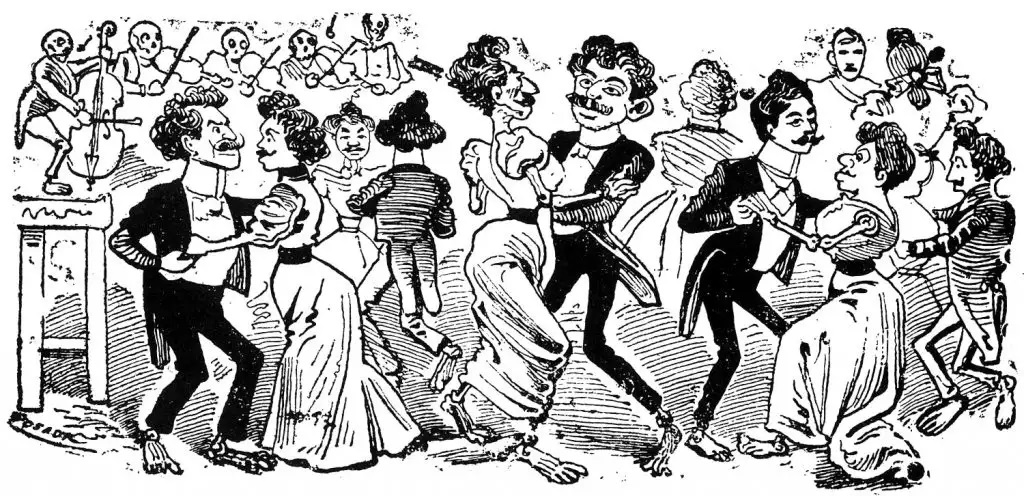

At the party, police found 41 men dancing together – about half of them dressed as women. Quickly, and without a trial, the authorities punished the participants of this clandestine drag ball, as observers might think of it today. Some of the offenders were forced to sweep the streets in their feminine attire. Newspaper records from the time show that the men were then put on trains and sent to the Yucatan peninsula, where they were forced to labor in support of soldiers fighting in an ongoing war with Mayan communities in the area.

Nearly seven decades before the Stonewall Riots sparked a movement in the United States, the scandal was a seminal moment in Mexican queer history. “The raid invents homosexuality in Mexico,” the Mexican essayist Carlos Monsiváis wrote of the event and its impact on popular culture. At the time, the revelation of an organized group of gay and queer men was discussed at length, and often with a mix of humor and contempt, in the press. The participation of men from Mexico City’s elite made the event particularly scandalous.

“It was the biggest scandal of the century. It was so controversial,” David Pablos, a filmmaker and the director of a film based on the event and premiering November 19, told AQ.

Initial reports of the party that night in 1901 counted 42 men in attendance, but the number was later revised to 41. The 42nd man, as the story goes, was Ignacio de la Torre y Mier, the son-in-law of Mexico’s then President Porfirio Díaz. Rumors endure that his connections to power spared him from suffering the fate and humiliation of his peers.

Over time, the number 41 came to carry a stigma, even as the details of what happened in 1901 were nearly forgotten in the ensuing years of revolution and national transformation.

“The way the legend remained alive was through this stigma of using the number 41 to accuse men of being effeminate and implicitly homosexual,” said Dr. Robert McKee Irwin, a professor at the University of California Davis. For decades, people consciously avoided the number 41, leaving the number off street addresses, military and police units, and hotel rooms, for example.

“By the time several generations went by, the vast majority of the people who were avoiding the usage of 41 in a kind of vague, homophobic way had no idea where the stigma came from,” Irwin told AQ.

More recent generations of LGBT Mexicans, however, have begun revisiting “the dance of the 41,” as the incident became known, as a foundational part of their history. Gay activist and intellectual circles engaged with the topic thanks in part to a 1964 novel about the 41 by the Mexican author Paulo Po, said Irwin. But it wasn’t until the 1990s and 2000s that consciousness about what happened in 1901 really grew. The rediscovery and publication in 2010 of a lost 1906 novel on the event contributed to greater awareness of the 41’s significance.

“The dance of the 41 was the first time that homosexuality was made visible. It revealed that there was an organized group of homosexuals and that they had formed a community,” said Pablos. “So in one way the gay community has come to see this as its coming out of the closet.”

Last year, organizers commemorated the 41st annual Mexico City LGBTI pride parade by paying homage to the dance of the 41. Now, Pablos’ film, due out in November and starring Alfonso Herrera, marks another renewal of this episode in Mexico’s queer history.

For Alberto B. Mendoza, the executive director of the National Association of Hispanic Journalists, learning about the story of the 41 as an adult brought closure after he had spent his teenage years on the U.S.-Mexico border being teased by peers who called him “41.”

“When I heard the story of the 41, for some reason I felt connected,” Mendoza told AQ. “I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m not alone.’”

In 2013, Mendoza started Honor41, a non-profit organization that celebrates the stories and accomplishments of the LGBT Latino community in the U.S.

“I think when people learn about the story of the 41, they get excited,” Mendoza said. “I think it’s important to see themselves in history and to see that our LGBTQ past isn’t completely erased.”

That sentiment of ownership is part of what’s driving Pablos’ production of the film.

“There’s a historic debt with this story that has somehow always remained on the edges, in the shadows. It’s always been a taboo,” Pablos told AQ. “It feels essential for this story to be told on the big screen, in a dignified way and with Mexican production.”

To tell the story authentically, Pablos made it a point to ensure most of the actors playing the 41 party-goers were in fact openly gay.

“It was really beautiful for me to see this brotherhood that was generated between this group of men,” said Pablos. “Something very beautiful about the gay community is how it can face so many things that are meant to be negative, how it can take the taunts – and find unity in them.”