MEXICO CITY — The initial display of Donald Trump’s “America First” foreign policy bore almost instant fruit earlier this month in Panama. Following a visit by U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio, President José Raúl Mulino announced Panama’s withdrawal from China’s Belt and Road Initiative and indicated that his government might reconsider the concession granted to Hong Kong-based Hutchison Ports, which operates key terminals at both ends of the interoceanic canal.

Although the decisions by no means eliminate China’s influence in Panama, they mark a diplomatic recalibration and a shift toward closer alignment with the U.S. However, not every country in the region will follow the same path. Each Latin American nation will navigate the U.S.-China power struggle differently, balancing strategic pressures with economic realities. Against this landscape, the U.S. will need to dedicate time and resources to a region that has for years felt left out of Washington’s priorities.

Over the past two decades, while the U.S. focused on the War on Terror and conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, China strategically expanded its economic presence in Latin America and the Caribbean, transforming from a peripheral player into a key trading partner. Former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers acknowledged that he underestimated this shift: “When a Latin American head of state asked me for something, I lectured them. While I was preaching, the Chinese were building airports.”

How the U.S. will reclaim its leading role in the hemisphere remains uncertain. The cases of Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina—the three largest economies in the region— are set to test the extent of the White House’s new ambitions and needs. President Trump is eager to adopt a tough stance with governments unwilling to comply with his directives on immigration and related matters—as reflected in the recent impasse with Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro—but it is not yet clear whether the hemisphere will rapidly realign with Washington or continue toward a trade-driven relationship with Beijing.

Traditional and non-traditional allies

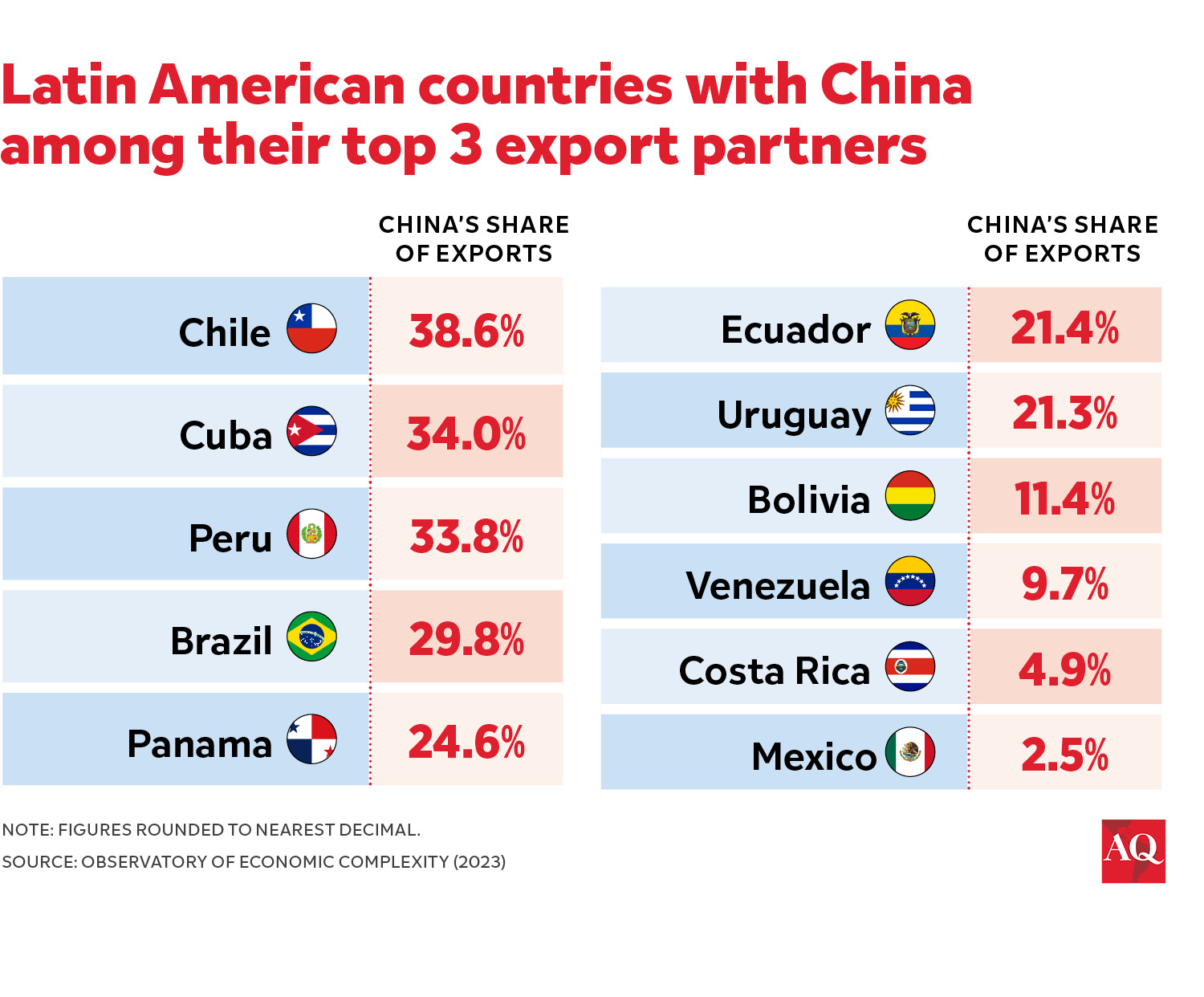

China has established a significant presence in many nations across the Western Hemisphere by lending to countries in urgent need, donating public libraries, building ports and roads, and extracting iron ore and vital minerals. Furthermore, trade between China, Latin America, and the Caribbean soared from $12 billion in 2000 to $315 billion in 2020, with projections indicating it could surpass $700 billion by 2035. China is now South America’s largest trading partner, with Brazil’s trade with China exceeding its trade with the U.S. by more than two to one. Beijing currently maintains “strategic partnerships” with 10 of the 11 South American nations it engages with, with Guyana being the only exception, as it maintains only standard bilateral relations.

In January, during a visit to Beijing, I met with Chinese business leaders whose inclination to deepen their investments in Latin America, particularly in Mexico, was unmistakable. Our discussions revealed China no longer perceives Latin America as a resource supplier but as a pivotal part of its ambitious global economic agenda. To illustrate the complexity of this reality, consider Colombia. Seen by many as the staunchest and most loyal U.S. ally in the region, the U.S. is Colombia’s top trading partner, in contrast to the several South American countries whose largest trading partner is China. Still, Chinese imports have surged in recent years, making the Asian behemoth the country’s second-largest trade relationship.

Guatemala also occupies a unique position in this rivalry. The country maintains a free trade agreement with Taiwan, a distinctive stance in a region where most nations have shifted diplomatic recognition to Beijing to align with its One-China policy. This makes Guatemala an anomaly in Latin America and provides Washington with a natural foothold to strengthen its influence. Also in Central America, Nicaragua and China recently inaugurated a direct maritime route as part of the Belt and Road Initiative’s expansion.

On the other hand, Brazil—Latin America’s largest economy—is largely a lost cause for Washington, as it has significantly deepened its ties with Beijing. Chinese firms have invested in major infrastructure projects ranging from ports and railways to power grids. China is now Brazil’s largest trading partner, absorbing most of its exports, including soy, beef, coffee, and iron. In 2023, bilateral trade reached a record $181 billion. Moreover, Brazil and China have strengthened their geopolitical ties through BRICS, further complicating Washington’s ability to exert influence.

Mexico’s case

Mexico is one of Washington’s most significant cases, given its deep economic integration with the U.S. through the USMCA. A recent article in The New York Times highlighted that China’s growing presence in Mexico’s auto industry is a key factor driving Trump’s push to expedite the USMCA trade agreement review. Since 2018, Chinese investment in Mexico has surged by 50% annually. In 2024, Mexico became China’s second-largest auto market, surpassed only by Russia. Manzanillo, the country’s busiest port, has seen a substantial rise in imports since 2020, mainly driven by Chinese goods. According to Norwegian logistics firm Xeneta, the Mexico-China trade route is now the fastest-growing in the world. Chinese companies have also played pivotal roles in major infrastructure projects in Mexico, including the Xochimilco-Tasqueña light rail and metro system upgrades in Mexico City and Monterrey. Even more, a recent study by Rice University’s Baker Institute suggests that Chinese investment in Mexico may be ten times higher than official figures indicate.

Trump understands that China’s presence in Mexico doesn’t technically violate USMCA terms, but that won’t alleviate his concerns. The idea of his primary geopolitical rival being deeply embedded in his largest trading partner—and positioned just across the 3,000-kilometer U.S.-Mexico border—is unacceptable. Unlike other Latin American nations, Mexico’s trade relationship with the U.S. is not merely important—it is fundamental to its economy, making it more vulnerable to Washington’s efforts to curb Beijing’s influence.

Southern countries

In Argentina, President Javier Milei presents a unique dynamic. While he shares a strong ideological affinity with Trump, his country’s economic ties to China—especially in the agricultural sector—are significant.

The relationship between Argentina and China developed gradually between the 1970s and 2009, culminating in a major financial agreement: a currency swap between the Central Bank of Argentina (BCRA) and the People’s Bank of China (PBOC). The goal was to ensure Argentina’s exchange rate stability and strengthen bilateral trade. Since then, economic cooperation has deepened, with China becoming Argentina’s largest buyer of agricultural products.

Peru attracts the highest level of Chinese investment relative to GDP in Latin America. The most recent—and largest—of these investments is the Chancay deep-water port, designed to serve as a direct trade link between China and South America. Shortly after Trump’s electoral victory, one of his advisors even suggested imposing tariffs on goods passing through Chancay, which was inaugurated last November by Xi Jinping.

Operated by China’s Cosco Shipping, the port is positioning itself as a regional hub. A couple of weeks ago, a Cosco Shipping vehicle carrier arrived at Ecuador’s Manta port after first stopping in Chancay, offloading 558 imported vehicles, marking a first for this route. Days ago, Cosco Shipping announced a new service to transport Chilean cargo via Chancay starting next month. To complicate matters further, former U.S. Southern Command Chief Gen. Laura Richardson warned last year that Chancay could eventually house Chinese military infrastructure.

Over the past seven years, Chinese investment in Chile has surged by 1,300%, with notable acquisitions in strategic sectors. Chinese firms now control over 60% of Chile’s electricity distribution market following purchases like Chilquinta and General Electricity Company (CGE). In 2024, Ecuador’s banana exports to China surged by 28%, propelled by the free trade agreement signed between the two countries in 2023 and effective since May 2024. Meanwhile, in Bolivia, the Chinese consortium CATL BRUNP & CMOC signed an agreement with the state-run Yacimientos de Litio Bolivianos (YLB) to develop two lithium extraction plants in the Uyuni and Coipasa salt flats.

A strategic challenge for the U.S.

China’s presence in Latin America also carries significant ideological implications. The region has witnessed growing disillusionment with democracy—polling indicates that more than half its population would support an autocratic regime if it promised to address crime and economic stagnation effectively. But, since Trump views democracy as more of an obstacle than a priority, promoting democratic values in the region is of little concern to him. For Trump, the issue is not ideological but strategic: China represents a direct challenge to U.S. security. As a result, the White House is particularly concerned about Chinese infrastructure and technology projects in the region. Once again, the region finds itself at the heart of a great power rivalry.

The escalating geopolitical tensions between the U.S. and China in Latin America prompt the question: How far will Washington go to persuade countries in the region to take a side? It is likely that Trump, more than pushing for a complete Latin American decoupling from China, will forcefully push for derisking, targeting areas of China’s presence in the region that Washington perceives as posing potential security or economic risks to the U.S. Many Latin American nations may aspire to a movement similar to the Non-Aligned Movement, which permitted countries to remain neutral during the Cold War. However, today’s global landscape is vastly different. Unlike the Soviet Union, China possesses unprecedented economic power and influence, making neutrality a more complex proposition.