BUENOS AIRES – For many observers of politics and economics in Argentina, the defeat of the current left-of-center government in the 2023 elections seems like a foregone conclusion. With the economy on life support and the government racked by scandal, how could Argentines return to power the Peronist slate of Alberto Fernández and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner?

Yet paradoxically, the worse things get, the better chance the current government may have of winning reelection. As a sense of crisis pervades Argentine politics, many voters feel they need the support of an active state and a familiar political force. While some react to Argentina’s troubles with demands for reform, others cling ever more closely to the status quo and its Peronist defenders.

The current landscape, to be certain, is deeply discouraging. Argentina is on track to notch six years of grueling recession by 2023, after barely having emerged from a period of stagnation that lasted from 2011 to 2015. Per capita incomes today are down to 2006 levels, while inflation is nearing a 50% annual rate. While poverty has fallen by a third globally since 1990, in Argentina it has risen over the same time period. Child poverty is approaching record levels: A shocking 70% of children in the area surrounding Buenos Aires live in households below the poverty line. With school closures stretching into a second year, 1.5 million children have left the educational system, imposing a heavy toll which will last decades into the future.

The country’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic has been equally dire. The current total of 80,000 deaths in a country of 45 million puts Argentina on par with the U.S. among the worst hit countries in the world. What’s worse, while the U.S.—buoyed by its vaccine rollout—seems to be leaving the pandemic behind, Argentina is entering a brutal second wave. The government shares in the blame for this situation, having used the pandemic to find new opportunities for graft.

Government negotiations with vaccine manufacturer Pfizer, which had carried out a major vaccine trial in Argentina, fell through for reasons that remain unclear. Vaccines have been sourced in the meantime from Russia (Sputnik) and China (Sinopharm), as plans to produce doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine locally have been badly hamstrung by delays. Of the vaccines that did arrive on Argentine shores, many were improperly distributed to political allies and officials of the governing party, or their families and friends.

In the Argentine commentariat, many find it impossible for the government to recover from such a conspicuous run of mishaps. But instead of asking how good or bad this government’s performance has been, it may be more useful to ask what the median Argentine voter thinks or will be likely to think in 2023. In political science, the median voter theorem states that the election is won by whichever party can win the vote of the person right in the middle of the political spectrum. Half the country is to the right of the median voter, the other half to her left. If she votes with the left, say, then the left wins the election.

Studies suggest the median Argentine voter may take much convincing to back a free-market reformist challenger, even when times are bad. According to a survey conducted by Pew in 2014, Argentines are some of the least free-market-friendly people in the world. Asked whether they agreed with the statement, “Most people are better off in a market economy, even though this implies that some people are poor while others are rich,” 48% of Argentines disagreed. Only 33% agreed, the lowest number among countries surveyed—the corresponding number was 44% in Mexico, 60% in statist France, 76% in nominally communist China and a shocking 96% in Vietnam.

Argentina’s voters are poorer now and on average less educated than when this survey was conducted, both trends feeding the longing for a protective state. Fear of change is widespread, along with a sense that the status quo should be preserved at all costs. This is understandable: After decades of failed reforms, every attempt at change has left many worse off.

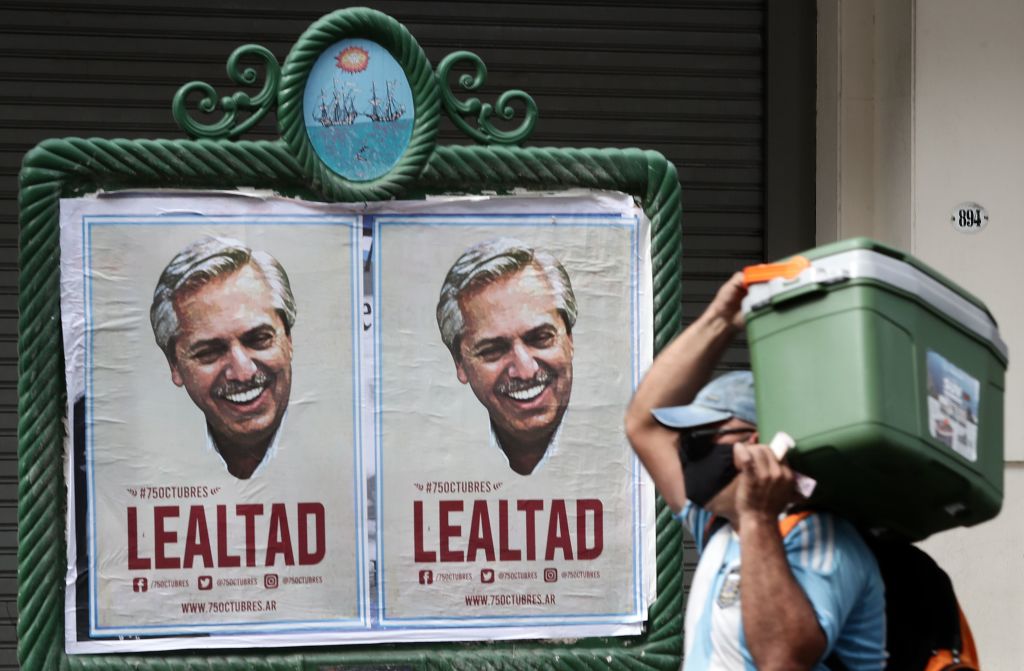

In this landscape, Peronism appears as the strongest and most reliable defender of the status quo. Each new crisis feeds the fearful mood, making this long-familiar force seem more appealing to many. In times of great uncertainty, the median voter often longs for certainty rather than reform. But could a Peronist slate really win in 2023, despite the accumulation of recession and scandals? It may seem impossible until we look at Venezuela.

As for Peronism itself, it has proven able savvily to shapeshift before each election, always presenting itself in a new form, as “justicialism” or “Kirchnerism,” yet always featuring the same anti-reformist core. To describe this phenomenon, the famous words of the twentieth-century Italian writer Giuseppe di Lampedusa come to mind: “Everything must change, so that everything can stay the same.” It is unlikely that any major political shift will occur in the upcoming midterm elections, before the end of the year. But it is unlikely to come in 2023 either. It seems that for progress Argentina will have to wait some time longer.

—

Sturzenegger is a full professor at Universidad de San Andrés, visiting professor at Harvard Kennedy School, and Honoris Causa Professor HEC, Paris. He is also former governor of the Central Bank of Argentina.