Latin America is not a monolith, although there are common threads among countries – including low access to financial services. Almost half of the people in the region lack a bank account, according to the World Bank – but most of the unbanked have access to a mobile phone. That explains why, despite concerns over their volatility and lack of government backing, many believe that blockchain-based currencies present a long-awaited path to finally bring the general public into banking.

“Fintechs were the promise to democratize access to the financial system in Latin America, but unregulated crypto came in and ate its lunch,” said Jaime Reusche, a senior analyst at the Moody’s ratings agency who has been following El Salvador’s saga as the first nation to adopt Bitcoin as legal tender. Reusche sees the decision as adding to the country’s already high credit risk. But the Salvadoran policy had financial inclusion as one of its tenets, and offered a $30 digital wallet to all citizens in a country where 70% of the population lacked a bank account. Four million people – of a total population of 6.5 million – have reportedly already activated digital wallets, and the government now plans to offer Bitcoin-backed loans to small businesses.

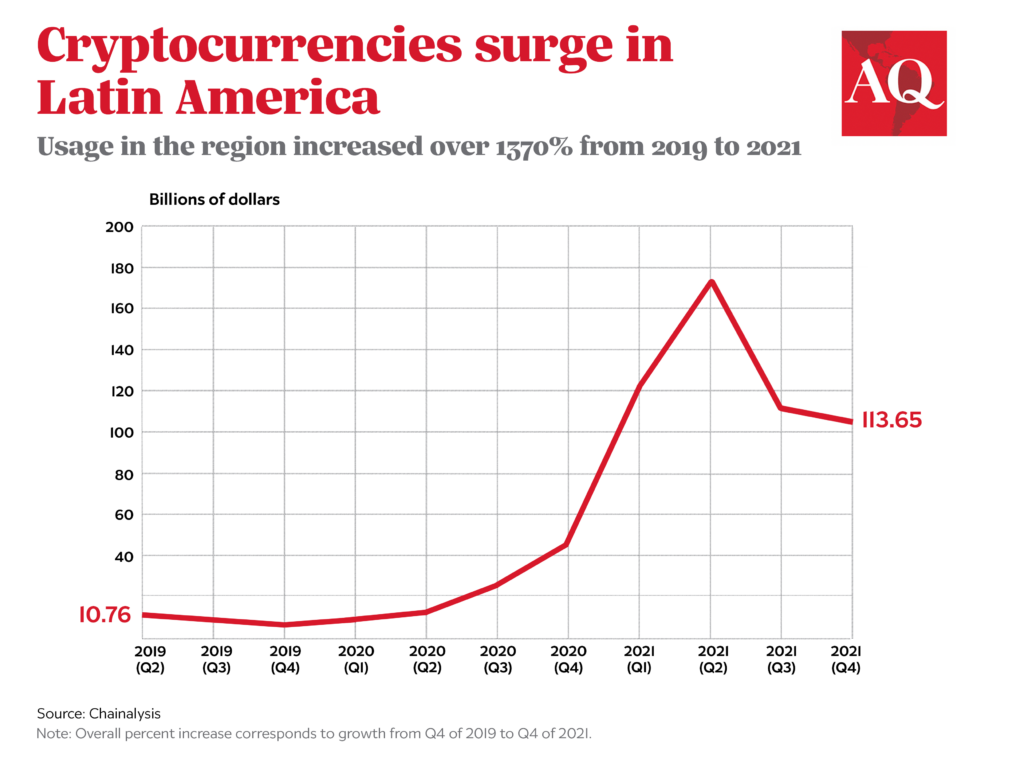

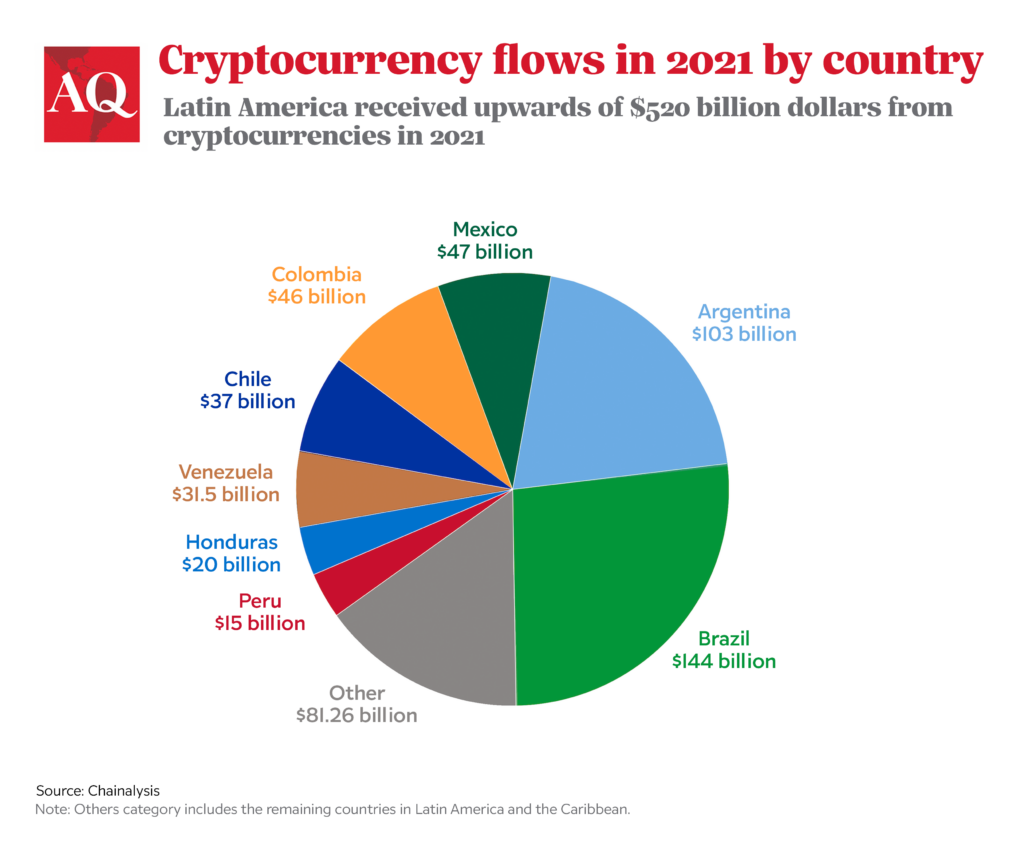

Indeed, 2021 was a landmark year for cryptocurrencies in Latin America. Globally, according to research firm Chainalysis, cryptocurrency adoption increased by a whopping 880% between June 2020 and July 2021, with the region as a whole ranking 5th in the world. “Latin America has consistently captured between 8% and 10% of global cryptocurrency activity,” said Kim Grauer, head of research at Chainalysis.

Migrants sending money home is a big part of this story in Latin America. Remittances are major sources of cash for many families – and economies – across the region. Salvadorans living outside their native land, for example, contribute some 24% of the country’s GDP – and transfers using Bitcoin or other non-national currencies are much cheaper than traditional services. Remittances in cryptocurrencies increased by 900% in 2021, according to Coinpay.cr, led by Mexicans in the U.S.

In Venezuela, the projected five million emigrants trying to make ends meet abroad have helped push the country to 7th in speed of adoption in 2021, with one of the highest rates of peer-to-peer use of cryptocurrencies. “In Colombia we have thousands of Venezuelans relying on our services to send money home,” Guillermo Torrealba, the founder and CEO of Chile’s Buda.com, told AQ.

Inclusion – and protection

Currency devaluation has also been a powerful cryptocurrency ally. Argentina ranked 10th in the Chainalysis global adoption ranking. “While there is no singular story for why a country may experience increased crypto adoption, we saw anecdotal evidence suggesting some people were investing as a store of value while their local currencies were depreciating,” Grauer told AQ.

“It can help us with inflation,” said Argentina’s President Alberto Fernández. Argentinians are moving savings from under mattresses to crypto wallets, and using it for everyday purposes. Local crypto exchange Lemon Cash had to increase the number of Visa credit cards it offered to account holders. “If your currency is as devalued as the bolivar or the peso, you’d look for protection – there was gold, now there is crypto,” said Alex Agostini, chief economist at Brazil’s Austin Rating.

The widespread use at the retail level led Colombia’s Superintendencia Financiera to launch a pilot program pairing the country’s largest banks with players such as Buda.com and Mexico’s Bitso. “It is a very restrictive environment, but it is progress as three years ago they were trying to prohibit crypto,” said Torrealba.

Superintendencia’s Jorge Castaño Gutiérrez said in a radio interview that the program aims to prevent the use of cryptocurrencies for money laundering and criminal and terrorist financing – although of course hard cash has long served that purpose well. He added that the program would allow regulators to better understand and control the crypto market.

In Brazil a bill is circulating in Congress that aims to regulate the market, as the country has already seen its share of criminals duping investors looking for get-rich-quick schemes. “Once crypto assets are regulated, with more transparency, adoption will tend to increase further,” said Agostini.

The other avenue on the radar is for central banks to issue their own digital currencies, or CBDCs. While CBDCs do not have the decentralized nature that attracts investors to Bitcoin or Tether, they too can lower the final cost of financial services as well as fulfill, for example, purchases in the virtual world. Mexico announced it will have a CBDC by 2024, and Brazil launched a competition for providers to offer solutions. Brazil is also taking part in related discussions with global peers. “Just seeing the appetite for virtual assets and tokens would justify us developing a safe virtual coin,” said Fabio Araújo, head of the Central Bank’s Real Digital project. But he said the main challenge is to develop global standards. “A virtual coin doesn’t see borders. We need a level of coordination that has never happened before,” he said.

Brazil has already implemented a digital instant payment service, called Pix, which functions as a virtual currency. This system has helped millions of previously unbanked Brazilians get access to transfers using just a phone number, email or other digital signature of their choice. “Fifty million people completed their first-ever electronic transaction since it went live in 2020,” Araújo told AQ.

The trend in the region is not lost among venture capital firms. Investments in this sector jumped from $68 million in 2020 to $658 million in 2021, according to industry group Lavca. The largest recipient was Brazil’s Mercado Bitcoin, which saw its business jump by 530% to trade some 40 billion reais of cryptocurrencies in 2021 – more than all their combined volume since the start of operations in 2013.

For Torrealba, the most practical side for Latin America is the extraordinary reduction in costs for financial services, and he sees the technology being mainstream soon. “I would compare to sending an email in 1994. It was possible, but not many people could receive it. Now look at where we are.”