This article is adapted from AQ’s latest issue on the politics of water in Latin America

It is long past time for everyone to realize that our exploitation of this renewable resource has limits and that we must learn to use water more wisely. Water scarcity threatens food security and nutrition, can lead to conflicts, and jeopardizes livelihoods and ecosystems if not addressed properly. In 2015, more than 660 million people had no access to improved drinking water globally.

Droughts are becoming increasingly common; proactive approaches to better water management are urgently required. We cannot stop a drought from happening, but we can prevent a drought from becoming a famine.

There are many reasons for water scarcity. Economic development and growing populations caused water use to grow twice as fast as the world’s population over the last century. Poor water governance and lack of investment have also contributed to a situation where supplies are not reaching those who need them.

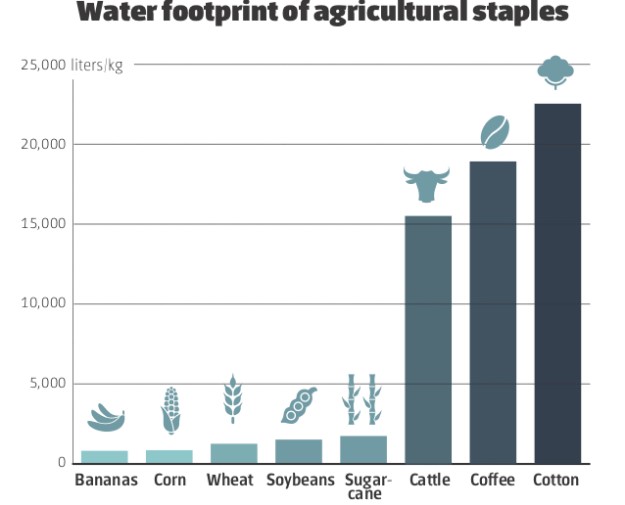

Agriculture is both a cause and a casualty of water scarcity. Farming accounts for around 70% of fresh water withdrawals. Irrigated agriculture provides 40% of all crops, yet 84% of the economic impact of drought falls on the sector. Against this background, agriculture will have to produce around 50% more food by 2050. As the trend in diets is moving toward meat and dairy, which require a lot of water to produce, we can expect an even greater pressure on resources.

A transformation of our food systems must be part of the solution. Actions to produce more with less water and reduce losses in agriculture have wider benefits, including in goals related to combating extreme poverty, hunger and malnutrition, and climate change. This also needs to include a radical change in our dietary patterns, as recently alerted by the last report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Source: Water Footprint Network; Note: Figures in kg produced of food material

Source: Water Footprint Network; Note: Figures in kg produced of food material

Actions and strategies must address water use, agricultural production, food security and climate change in an integrated manner. The FAO-led Global Framework on Water Scarcity in Agriculture, launched during the UN Climate Change Conference in Marrakesh, Morocco, brings together the top minds in water and agriculture to design these strategies.

Action on food loss and waste will also help. To save water, we need to address food waste across the whole value chain, from fork to farm and from source to sea. Add this to responsible consumption and more sustainable diets, and our water, land and soils will benefit — with the bonus of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

The private sector is another piece of the puzzle. Businesses are already aware of the potential hits to their bottom lines — in 2016, the world’s largest companies reported $14 billion in losses from water-related issues.

But there are inspiring examples to be followed. In 2003, the Brazilian government launched a program to build 1 million cisterns to collect rainwater in the northeast region. The installation cost of each small cistern was less than $1,000 and it allowed families to have access to drinking water during eight months of drought. With the support of FAO, similar cisterns are being constructed in Africa, particularly in the Sahel, and in Central America. It has been proven to be a significant solution to empower rural women, previously forced to walk several miles to collect water — mostly while holding their children.

In this context, it is worth noting that the Sahel is located at the same latitude as the Amazon. Millions and millions of years ago, that African region was also a tropical forest. Following massive episodes of deforestation and fires, the Sahel turned into an extension of the Sahara Desert.

It means that the current episodes of fires in the Amazon could jeopardize the world’s largest reserve of fresh water. If this happens, not only will the forests be compromised, but also the rich local biodiversity and food security of local populations. Livelihoods of residents of Amazon regions— including indigenous peoples — depend on the forest. Desertification and hunger are interlinked.