Five years into Lava Jato, Odebrecht continues to break records. In recent months, the Brazilian construction conglomerate filed – in Brazil and the U.S. – for the largest-ever bankruptcy in Latin America, trying to restructure over $25 billion of debt and avoid asset seizures.

Given the $788 million trail of corruption and political mayhem it has left across 12 countries, some observers wouldn’t mind watching the company burn to the ground. But is the total collapse of Odebrecht ultimately good for the fight against corruption?

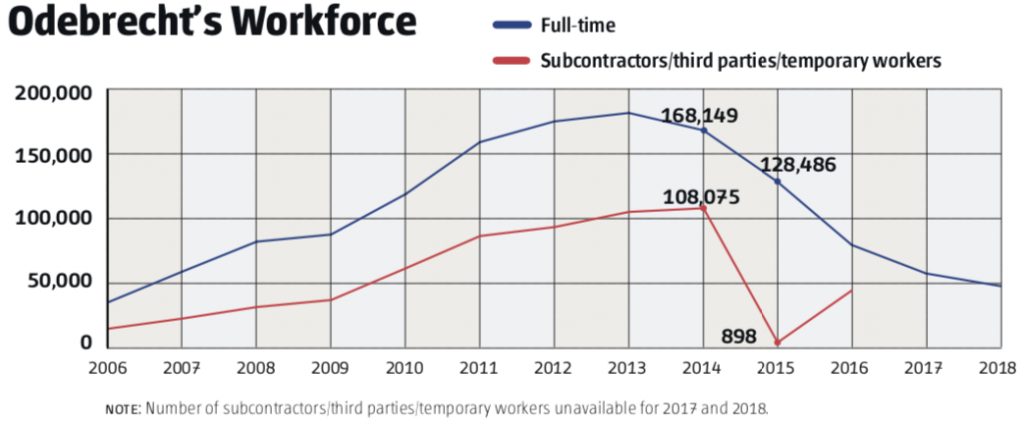

Unless one believes that the entire company was a criminal enterprise with no positive economic or social impact whatsoever, the answer is no. According to data from Odebrecht, over the first three years of Lava Jato, the company eliminated almost 90,000 full-time positions worldwide (other factors, particularly the slowdown across Latin American economies, certainly contributed to the decline).

Source: Odebrecht Annual Reports

Source: Odebrecht Annual Reports

Taxpayers in countries like Brazil and the Dominican Republic will help foot the bill for the bankruptcy: Odebrecht’s most exposed creditors are Brazilian public banks – BNDES alone could pick up a $3.6 billion tab – and the filing includes part of the company’s $180 million settlement with the Dominican government. Millions of citizens are still suffering the consequences of 45 Odebrecht projects – from a gas pipeline in southern Peru to highways in Colombia – that remain stalled or have been abandoned. For all these people, the company’s debacle is in fact terrible news.

Odebrecht’s extreme case exposes a broader issue for anti-corruption in Latin America. Some countries have developed powerful tools to detect grand corruption and punish companies. Yet they still lack mechanisms to “remove the cancer without killing the patient,” as one veteran white-collar crime attorney said. In order to contain the economic damage and ultimately strengthen anti-corruption enforcement, Latin American countries need to find more efficient ways to penalize companies.

This means seriously punishing the individuals responsible for crimes, levying penalties that outweigh improperly obtained benefits and imposing internal controls to prevent the problem from happening again. But it also means actively working to preserve the good parts of the firms in question.

Some Brazilian authorities involved in Lava Jato immediately understood this challenge. “Alert: (Odebrecht) cannot go bankrupt. If it does, we are going to lose legitimacy,” a senior prosecutor texted his colleagues in 2016, according to leaked messages exchanged between Lava Jato investigators. At the time, the company and prosecutors were finishing plea negotiations. “The settlement (between authorities and the company) – it’s like this around the world – needs to save jobs. We have to be very careful about this.”

An underdeveloped regulatory framework is one of the main challenges. From Brazil’s 2013 Clean Companies Act to Costa Rica’s Statute 9699 approved in June, congresses throughout Latin America have approved a flurry of corporate liability laws in recent years. They vary in quality, but unquestionably the region has better legislation to address the problem than it did a decade ago. Now, the question is becoming increasingly political: Can these young democracies develop the institutions, procedures and culture to efficiently enforce the new rules on the books?

Odebrecht’s lawyers in Brazil had to simultaneously negotiate a leniency agreement with more than five different government agencies, amid high legal uncertainty. Three years later, it remains unclear which parts of the Brazilian bureaucracy have a say in plea deals. Meanwhile, even with an agreement in place, most Odebrecht projects in Brazil are still paralyzed.

Late last year in Peru, Odebrecht agreed with prosecutors to fully cooperate and pay a $200 million fine, in return for resuming its operations in the country. However, a judge later decided that the deal was illegal, throwing it into a judicial limbo. Its collapse could prevent prosecutors from advancing investigations, while extending the economic pain caused by the frozen investments.

The business and political landscape in Latin America also poses challenges. One example is the relationship between executives and companies. Numerous Latin American corporations are family-owned or controlled – including three of the 10 largest business groups in the region – which makes it harder to separate individuals from legal entities. When family and business ties overlap, companies are probably less likely to fully cooperate.

Based on the leaked Lava Jato messages, Brazilian prosecutors considered forcing Odebrecht executives – including members of the Odebrecht family – to sell all their shares, but soon concluded that the measure lacked a clear legal basis. A bill with this provision, formulated by a group of legal scholars, is in the early stages in Congress. The academics propose shifting the focus of enforcement against companies: instead of penalizing them by cutting access to government contracts, guilty executives and directors would bear the burden, having to fully divest in fewer than two years.

Another key political issue for punishing companies is public opinion. The perception that corrupt firms are not paying enough and are getting away with graft will immediately undermine authorities’ efforts, no matter how well-intentioned. This is true everywhere, but it may be even more so in Latin America, where voters – from Mexico to Colombia, Brazil to El Salvador – have been putting corruption at the top of their priority list.

Odebrecht’s spectacular collapse should emphasize the importance of stronger institutions and better norms to minimize the pain that grand corruption inflicts. The company has broken many records, but it will not be the last one to test the limits of anti-corruption enforcement in Latin America.

—

Simon is head of AS/COA’s Anti-Corruption Working Group and politics editor for AQ. Sweigart is policy consultant for AQ.