China’s $1 trillion plan to remake the global order astonishes not only for its audacious scale, but also its geographic reach. The “One Belt, One Road” initiative is the backbone of a transformative geopolitical and economic agenda. President Xi Jinping’s brand of globalization dispenses with the old liberal order and is bending international trade in the country’s favor. The plan involves massive infrastructure projects in over 60 countries. Focused on securing trade routes in Asia, Europe and Africa, some Latin Americans have grumbled about feeling left out of the Chinese bonanza. These grievances are misplaced.

To be sure, Latin America is squarely in the sights of the Chinese government and investors. Already Brazil’s leading trading partner, China’s presence in the country is set to increase dramatically by next year. In 2015, Xi committed to almost doubling two-way trade with the region to $500 billion within the decade. He also intends to increase investment by another $250 billion by 2020. Once heavily concentrated in commodities and manufacturing, Chinese firms are now exploring new ground, from logistics to renewable energy.

Seeing opportunity in the sweeping privatization programs announced by Brazil’s President Michel Temer, Chinese state-owned companies, led by State Grid and China Three Gorges, are seeking to expand their assets in the country – as are a growing number of Chinese private firms. That this is occurring during a period of a relative slowdown in China’s own economy is noteworthy: GDP expanded by 6.7 percent in 2016 – high by global standards, but a drop from the double digit growth experienced in the past.

Brazil could use a cash injection. It has only barely started to recover from three years of economic recession and the government is rapidly putting major public assets on the auction block. Chinese acquisitions are set to both expand and diversify into new sectors. The Brazil-China Chamber of Commerce estimates that investment from Chinese companies could reach $20 billion this year alone. This growth may accelerate considerably next year. The government plans to conduct 72 auctions in 2018, including for airports, highways, oil fields, water and waste facilities, indebted power companies and electricity lines.

Such investments will require dramatically increased coordination and cooperation between Brazil and China. In 2015, the two countries announced a $50 billion investment package. These types of arrangements are now likely to multiply. In early 2017, for instance, Brazilian and Chinese officials announced a $20 billion investment promotion fund through which China will match every dollar invested in these Brazilian projects with another three from China, focusing on infrastructure, manufacturing, agribusiness, and new technologies.

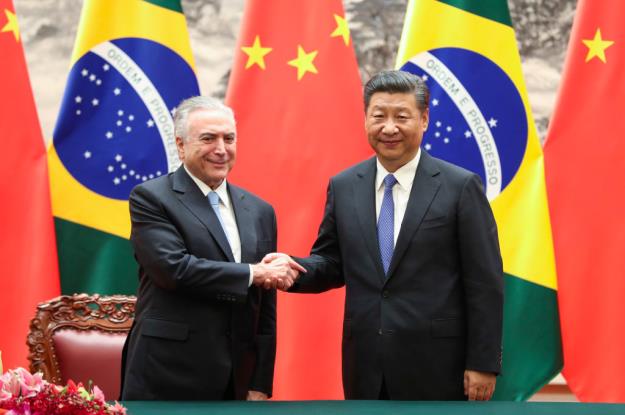

The Brazilians are clearly rolling out the red carpet. The embattled Temer is working to overhaul Brazil’s regulatory framework and undertake a broad privatization of major assets. In his trip to Beijing earlier this month, Temer met with Xi and urged greater investment in Brazilian infrastructure, highlighting the demand across sectors such as electricity, railways, roads, ports, and agriculture. The federal government is hardly the only player courting China. Major cities, such as São Paulo, and several states, including Bahia and Ceará, are also hoping to strike new cooperation deals with Beijing.

For China, the importance of Latin America has increased in recent years, due in large part to Beijing’s desire to ensure greater domestic energy and food security. China clearly views Brazil as a vital source of strategic resources. Less explicit is China’s desire to counter the geopolitical influence of the United States and benefit from its waning soft power in the region. While most of China’s investments are shaped by a traditional cost-benefit calculus, others are considered sufficiently politically strategic in the long term that losses will be tolerated. In the meantime, Chinese investments will absorb the increased risk associated with political turbulence in Brazil.

As China moves from mergers and acquisitions to more greenfield investments in Brazil, activists worry about the potential environmental impacts and the former’s adherence to labor and human rights standards. Some economists also fear that dramatically expanded Chinese investment could negatively affect wages in Brazil’s manufacturing sector. They have good reason to be concerned. Brazilian public authorities and watchdog groups hope to avoid the mishaps of Chinese investment in neighboring Ecuador, Peru and Chile, where some corporate practices led to environmental damages, social tensions and popular backlash.

For the most part, however, Brazilians seem less preoccupied with the origins of Chinese investment or China’s record in Latin America and Africa, than with the potentially damaging impacts of a sudden inflow of massive investment. A veritable flood of capital is on the way, as is a much more expansive presence of Chinese business. If well harnessed, the incoming torrent of Chinese investment could help to unleash new and dynamic economic growth and sustainable development in Brazil. But there the incoming wave of investments could just as easily lead to a free-for-all, exacerbating pre-existing inequalities and social tensions in the process.

The real question is whether the next generation of Brazil’s legislators, regulators and business leaders have the foresight and integrity to guide these new investments wisely. To be sure, Brazil’s civil society already has its hands full monitoring its own political and economic class, much less the arrival of the Chinese.

—

Muggah is a co-founder and research director of the Igarapé Institute.

Abdenur is a fellow at the Igarapé Institute.