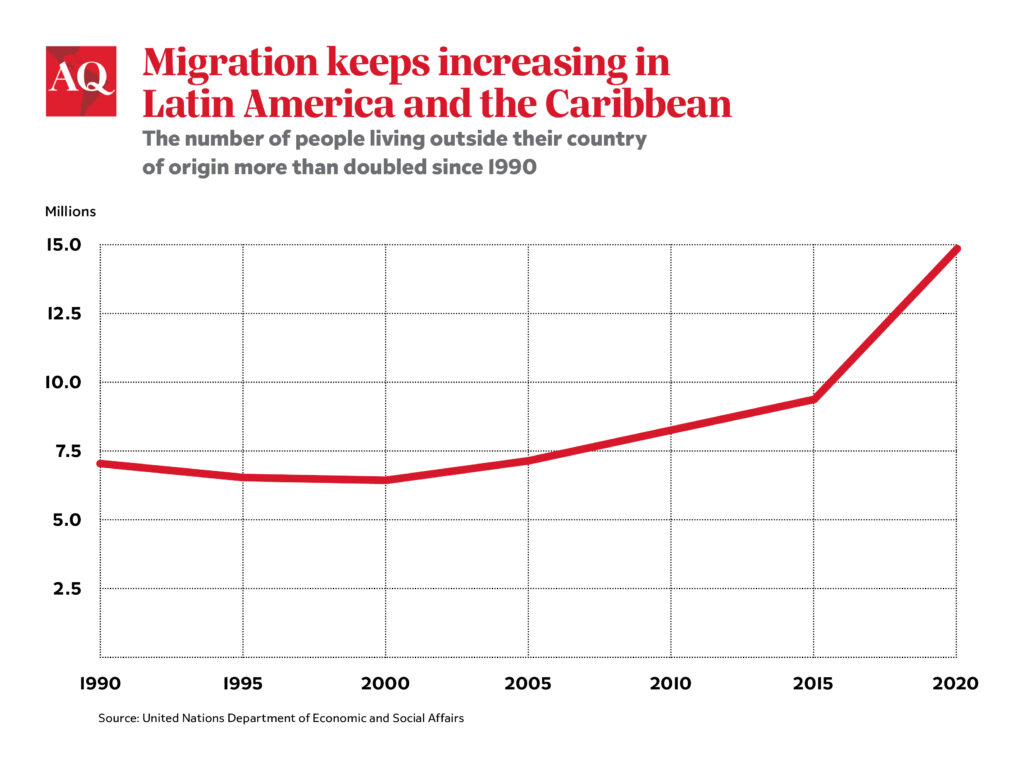

Almost all countries in the Western Hemisphere are dealing with significantly increased migration over the past few years—and nations big and small are trying to figure out how to balance their humanitarian commitments to those fleeing displacement crises with a desire for clear and orderly pathways for people to cross borders. The number of immigrants living in Latin American and Caribbean countries has roughly doubled since 2010, and most of the region opted to provide a legal pathway for displaced migrants. But the pendulum appears to be swinging towards a desire for greater control of borders in the region, much as in the United States, which has seen some of the largest migrant arrivals in history at its border since 2019.

Several countries have imposed visa restrictions on Venezuelans, Haitians and other nationalities, and most are trying to get a handle on how many new immigrants they can take each year. Costa Rica recently made asylum harder to get, while Chile has even stationed army troops on the border with Bolivia and Peru.

The Biden administration too is trying to get greater control of its southwest border with Mexico after a period of large-scale arrivals. It has begun expelling migrants from Venezuela, Nicaragua, Cuba and Haiti, for example, while allowing expanded legal arrivals through a new sponsorship program for people from those countries who apply online. They have also increased deportations and expulsions of other Central American migrants directly to their home countries, rather than just expelling them to Mexico, but are trying to balance this by expanding seasonal employment visas to provide broader options for legal migration pathways to the United States.

And, in perhaps their most controversial decision yet, they have proposed a rule to make it extremely difficult for most migrants to apply for asylum between ports of entry, hoping to require those seeking asylum to use an orderly process at the ports of entry—the legal crossing points—instead. It remains to be seen whether this is workable given real capacity constraints at ports of entry, and whether the courts find it to be legal, but the idea is to provide order to the asylum system while slowing unauthorized crossings at the border.

What happens in the United States will reverberate in the rest of the region, and the remaining countries in the hemisphere will be watching what the Biden administration does. If these measures manage to restore a degree of order at the border while also expanding legal channels for entry and preserving meaningful access to asylum, other countries are likely to keep making the same efforts they are already pursuing to create balanced migration policies. After all, order and openness are compatible objectives if done right.

However, if the U.S. measures end up restoring border control at the expense of asylum and legal pathways, many other countries will take it as a signal to pursue a more restrictive approach too. If so, this would undermine the impressive openness and pragmatism demonstrated by Latin American and Caribbean countries during this period of unusually high regional mobility. Colombia’s 10-year residency permit for Venezuelans is just one example; most countries in the region have tried to provide some form of legal status to those who were displaced, as well as access to schools. Many have also tried to regulate more routine migration flows with labor agreements that allow for seasonal work or regional mobility agreements that allow for legal movements across borders of nearby countries. A more restrictive approach would instead incentivize more irregular migration.

Last June, at the Summit of the Americas, 21 governments in the hemisphere —including the U.S.—signed the Los Angeles Declaration on Migration and Protection, which laid out a set of principles designed both to ensure a degree of openness to migration and to create more orderly and predictable movements across borders. Signatories pledged to strengthen legal pathways, invest in asylum systems, and work on providing legal status to those living without documents in their countries, while also encouraging information sharing and coordination on policies that might allow for a degree of control over unexpected migration movements. And the agreement promised resources to those countries hosting large displaced populations.

It was a commitment among countries in the region to maintain their welcoming approach to migrants, especially to those fleeing danger, but to also create a framework for more orderly, safe and regular movements between countries. It was a balancing act between countries’ desires to preserve their humanitarian commitments and their desire for greater control of who arrives. The promise of new funding from donor countries and multilateral development banks to support these efforts was critical to its success.

It is a similar pattern to the United States, where polls show most U.S. citizens are overwhelmingly supportive of immigration but also worried about the southwest border. The question is how to balance between openness and control without sacrificing either one in the process. Most people in this country do not want a return to the restrictive approach of the Trump administration, but they want the Biden administration to pay more attention to creating an orderly process at the border.

This same debate is playing out across the region, and many are watching to see what the Biden administration does next on migration policy. Whatever happens at the U.S. border with Mexico is likely to have a powerful echo effect across the rest of the region. And this, in turn, will help decide whether a region known for its openness to immigrants and refugees can stay faithful to its traditions, while building more predictability into the process.

—

Selee is president of the Migration Policy Institute, MPI. Follow him @SeleeAndrew