Founded 1985

Vale’s net annual revenue from ferrous minerals $32 billion (2020)

Jobs created

9,600 from S11D complex at Carajás (direct and indirect)

Global market for iron ore

$124 billion (2019)

Brazil share

Vale accounted for 72% of Brazil’s national iron ore production in 2019

This article is part of AQ’s special report on sustainable development of the Amazon.

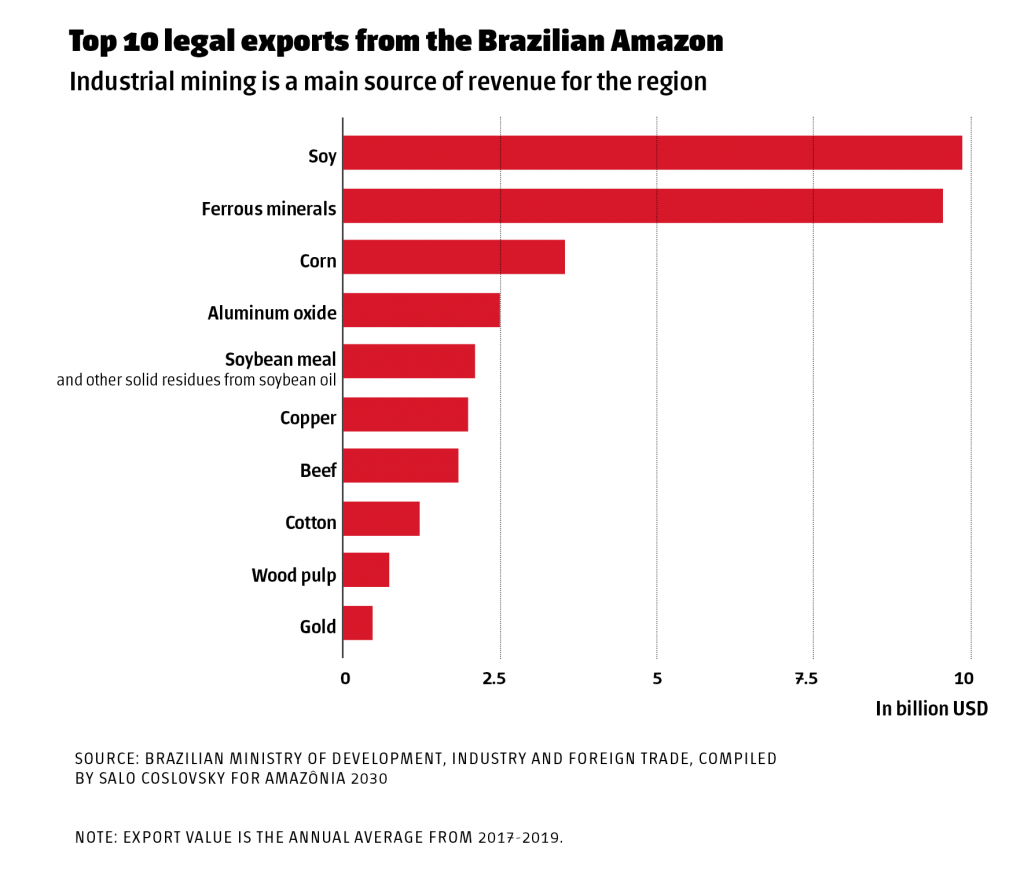

The blueprint for a sustainable economy in the Amazon may include a surprising industry.

While the harm from illegal, makeshift mines has been well-documented, “Legal, industrial mining has minimal impact when it comes to deforestation,” said Beto Veríssimo, senior researcher and co-founder of Imazon, an environmental NGO.

In the Canaã dos Carajás municipality of Brazil’s Pará state, the world’s largest iron ore mine offers what some call a model for more sustainable mining.

Operated by mining giant Vale, the mine sits on a 3,000-square-mile tract of forest, which Vale helps protect in partnership with the Chico Mendes Conservation and Biodiversity Institute. While 60% of Vale’s iron ore production comes from this area, the company’s activities take up less than 1.5% of the land, said Leonardo Neves, Vale’s environment manager in Pará.

After the deadly 2019 disaster at Vale’s mine in Brumadinho, Brazil, investors are demanding cleaner mining practices, reflecting pressure “to show they are investing in solutions, not problems,” said Júlio Nery, director of sustainability and regulatory affairs at the Brazilian Mining Institute.

Last May, Norway’s sovereign wealth fund divested an estimated $375 million in Vale stock, citing “serious environmental damage” at the mine in Brumadinho, where the collapse of a tailings dam (an embankment that stores mining waste) killed 270 people. In February, the company reached a $7 billion settlement with the state of Minas Gerais.

The Carajás mine offers a contrast – and the “best practices in terms of environmental impact,” said Barbara Mattos, a senior vice president for Moody’s Corporate Finance Group in São Paulo.

The mine does not use tailings dams, and more than 80% of all production in Carajás is done without the use of water, said Neves. A system of conveyor belts rather than trucks cuts down on emissions and fuel.

The 48-year lifespan of one of the mines suggests iron ore mining will likely be part of the Amazonian economy for decades. Surging Chinese demand made iron ore one of the best-performing assets of 2020, and Vale will spend $1.5 billion over the next three years to expand capacity at Carajás. While mining, by nature, is not sustainable, Carajás may show it is possible to reduce its long-term effects on the environment.