This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on China and Latin America

In the 19th century Valparaíso went through a remarkable transformation. With the beginning of Chile’s independence movement and the declaration of free trade for the port of Valparaíso in 1811, thousands of immigrants—mainly British, German, Italian, Spanish, French and Arab— began arriving. This influx fueled growth, and with it, Chile’s first bank, public library, private school, observatory, stock exchange, and a hub of technological progress.

In celebration of the city’s rich immigrant history, a new museum brings to life the journey that Europeans and Arabs made across the ocean and toward Valparaíso. The opening coincides with a period when the arrival of thousands of immigrants in Chile over the past decade has generated internal tensions, changing the course of the nation’s politics and once more the social fabric. Between 2018 and 2023, the foreign-born population increased by 47% to 1.9 million.

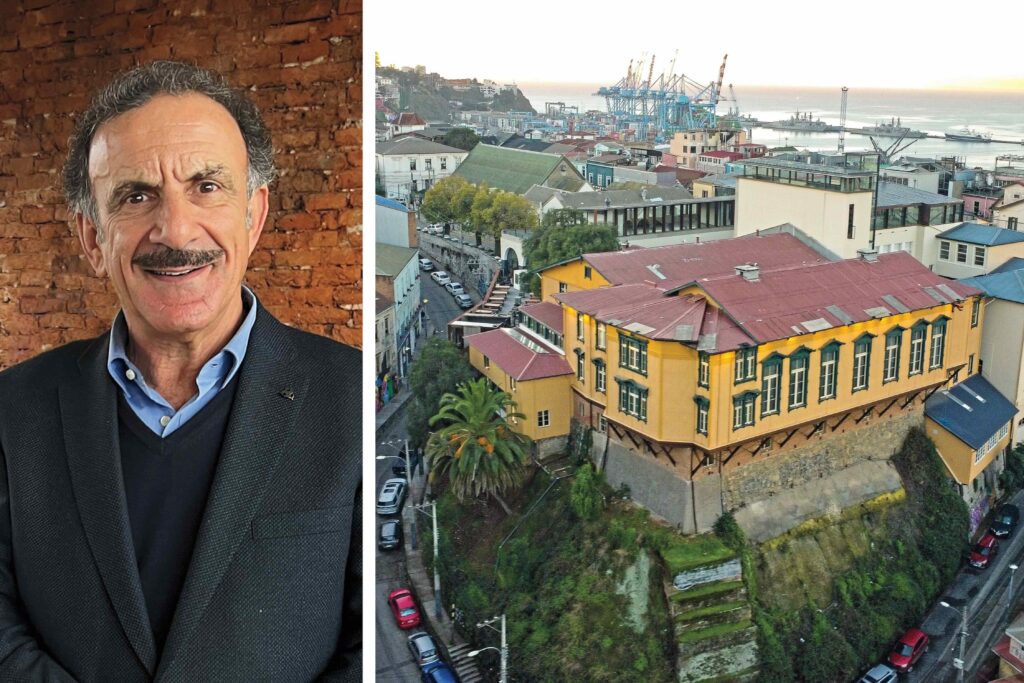

The Destino Valparaíso—Museo del Inmigrante opened in August in a building that dates back to 1869 and sits atop one of the city’s many hills. The Dib family, of Lebanese and Syrian descent, purchased the building in 2016 and undertook a renovation.

“This museum is a tribute to the people who crossed the world and arrived in precarious conditions in Valparaíso,” Eduardo Dib, leader and founder of the project, told AQ. The 1865 census shows that the port city had about 70,000 inhabitants, of whom about 5,000 were foreigners.

Through an audio guide and first-person storytelling, the 1,800-square-meter museum recreates the lives of those who traveled by sea and over the Andes Mountains to arrive at Valparaíso. Each migrant community has its own room. There are antique tennis rackets and golf clubs from the British, who introduced sports like tennis, football and golf to Chile. The exhibit also explores the founding of British schools and the city’s only Anglican church—built before religious freedom was granted in Chile, when Catholicism was the only legal faith. By 1931, Valparaíso was known as the most British city in South America, earning it the nickname “Liverpool of the Pacific.”

The Germans became the second most powerful community after the British. We learn about their history in banking, the introduction of classical music in Chile, and their work establishing pharmacies.

Sewing machines and shoe trees reveal the influence the French had on fashion and culture. In 1830, France established Valparaíso as its main supply port on the Pacific coast, favoring the settlement of French citizens. French priests of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts introduced private education to Chile with the school they founded in Valparaíso in 1837.

By the end of the 19th century, Italians had become the largest immigrant community, and the museum highlights their significant influence on food. Pesto, Pasqualina pie, and focaccia, popular dishes then and now, are the heritage of the immigrants from Liguria.

Arab colonies, we learn, made their journey escaping the Ottoman Empire, and they worked mostly in the textile industry. Today Chile is home to the largest Palestinian community outside the Middle East. The Spanish room describes how Asturians founded hardware stores and Basques and Galicians established bakeries.

Immigrants helped turn Valparaíso into a cosmopolitan city where English was widely spoken. “Coming here is like seeing all the stories of Valparaíso you heard as a kid,” said Juan Yuz, dean at Federico Santa María Technical University. Visitors from the Greater Valparaíso area can reconnect with their past through photos, food and objects. “Some even leave in tears after finding ancestors in the photographs,” said Dib.

Now, however, Valparaíso is far from its glorious past. Chile’s centralization in Santiago, the capital city, wiped out the innovation, commerce, fashion, business and finance that once made the port such a vibrant hub. Remembering and cherishing that past is the museum’s goal. “We want it to become a place where the past connects with the present,” said Dib.