Latin America is vulnerable to climate change in more ways than one. Many countries in the region are susceptible to extreme weather events. But big changes underway in the world economy should worry governments, too.

That’s because the measures the world adopts to accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels will inevitably affect the market for carbon-intensive commodities on which the region so heavily depends. Export volumes and prices related to fossil fuels are likely to decline in the medium and long term, according to the IEA and others. How will the region prepare financially for the challenge?

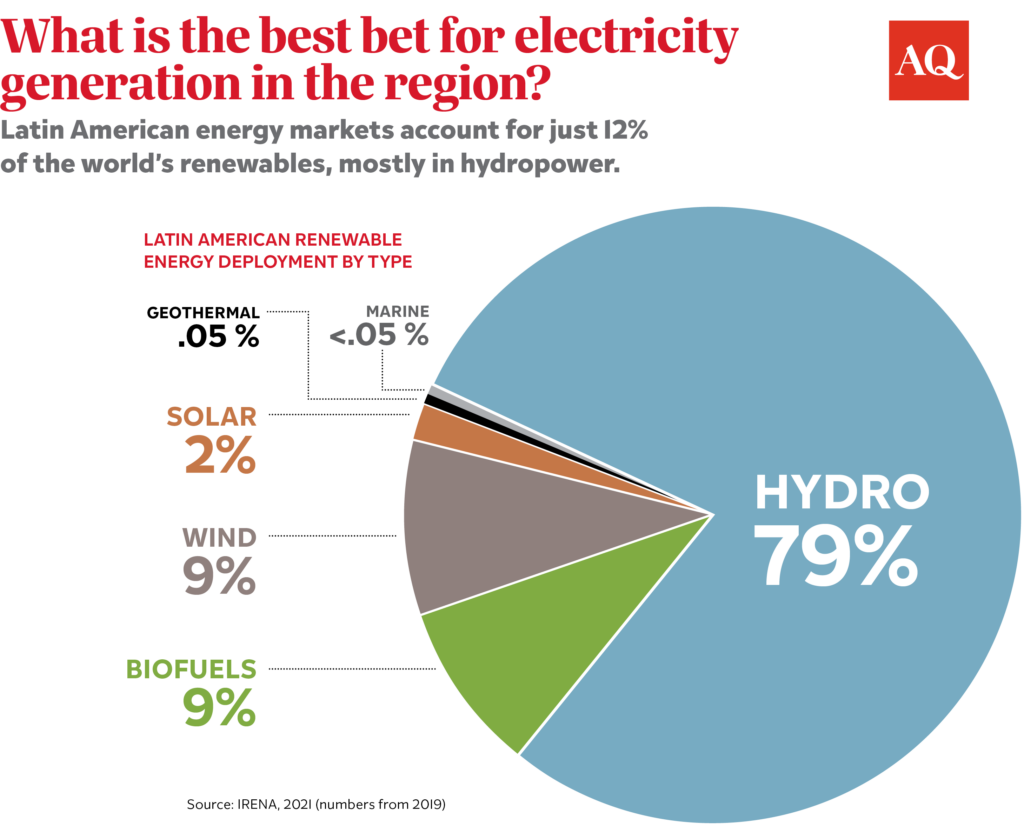

In one way, the region is lucky. Latin America has a host of options at its disposal to start to mitigate and address the carbon emissions of its legacy assets. More importantly it is well positioned to generate income from low-carbon fuels, renewable energy and carbon offsets.

But getting there will take commitment on behalf of the private sector and partnership with the public sector in pursuing bold policy strategies and revising institutional frameworks to make a true energy revolution possible.

Here’s a look at some of the biggest challenges and how they might be overcome.

The private sector’s role

In the short run, the additional revenues the region receives from high oil and coal prices need to be invested effectively and efficiently. But as things stand, in some countries there are few indications that existing institutional arrangements will push these resources toward improving resilience and helping ensure an orderly energy transition.

The IEA estimates the financing needs of the energy transition in emerging markets at $1 trillion annually between now and 2050. Given the scars of COVID – and current high levels of government debt – public investment will be constrained. This implies that the bulk of the energy transition will need to be privately financed.

One of the main obstacles to this is the cost of capital, which is significantly higher in Latin America than in advanced economies and even other emerging economies, including those in Asia. This is the product of several factors, including macroeconomic volatility, currency risks, underdeveloped local financial systems, and political risks and instability.

Dealing with these constraints is particularly important because financing the energy transition is not like financing fossil fuels. In extractive industries state-owned enterprises or foreign multinationals are ready to invest because rents compensate for the higher macro and political risks. This is especially true of countries with proven reserves and reasonable government takes. Extractive industries are also export-oriented, which means that they generate foreign exchange and thus are less exposed to domestic regulatory risks (such as prices controls).

By contrast, low-carbon industries are technologically-advanced, low-margin, and regulation-dependent. They are not significant sources of export receipts, at least initially. Moreover, low-carbon industries are not sources of fiscal rents – quite the opposite, renewable energy deployment often requires government support in the form of subsidies or special tax regimes. From the public finance point of view, the transition to clean energies implies a rethink of the tax structure, shifting to pro-growth fiscal strategies from rent-extracting fiscal dependency.

While the energy transition could bring significant opportunities for the region, capitalizing these opportunities – and the investments that come with it – is not assured. Mobilizing clean finance will require policy changes, new regulatory frameworks, and even the creation of new markets. All this points in the direction of effective governance and predictable policies.

The public sector’s role

A first priority should be to help the region’s more carbon intensive industries reduce their carbon footprint, which will allow Latin American economies and industries to remain competitive in an increasingly carbon-sensitive global marketplace.

The creation of markets and regulatory frameworks for both natural carbon offsets and technology-driven ones like carbon capture storage and utilization (CCUS) will be key. This is particularly the case for hard to abate sectors like cement and steel. The know-how of the fossil fuel industry is essential in deploying CCUS technology to create markets at home while decarbonizing their own operations and retrofitting existing infrastructure.

Nowhere are the policy and financial challenges more revealing than in clean hydrogen, which appears to have significant potential in transportation, heating and as feedstock but has yet to be developed commercially. Many countries have developed hydrogen roadmaps, including in Latin America. But apart from Chile, which is already developing hydrogen projects and has conducted hydrogen auctions, other countries in the region are either in the conceptualization phase or have not even started.

Latin American countries have two major natural advantages that they can leverage to make progress in the energy transition. One is the region’s reserves of strategic minerals, such as lithium and rare earths, which are crucial for the production of batteries and other equipment needed for the production and use of renewable energy. The second is carbon offsets given the region’s biodiversity.

To make the most of these advantages, the region can build on early successes of attracting investments in wind and solar electricity through auctions.

But in the future governments may need to rethink and expand their financial toolkits in four areas: effectively deploying international development finance, optimizing the capital structure of state-owned companies to resort to equity instead of debt finance, mobilizing local development banks and developing local and international green and ESG bonds markets more aggressively.

The financial toolkit

While the bulk of the financing is expected to come from the private sector, development finance could be instrumental in Latin America’s energy transition, particularly for countries where the cost of capital is higher and the size and depth of private capital markets is limited. Development Finance Institutions (DFIs), climate funds and climate-aligned Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) will be crucial components. DFIs should identify and scale up blended finance vehicles, instruments, and facilities that support significant mobilization of private capital particularly to finance less proven technologies and for de-bottlenecking infrastructure.

Financing the energy transition will also need to include de-risking instruments (e.g., loan guarantees, feed-in tariffs with transparent phase-out horizon, public procurement to guarantee initial demand for new products and services). Lending though domestic development banks can be critical by providing patient capital.

The presence of state-owned companies throughout the energy chain could provide an opportunity for equity financing as a way to rely less on debt financing to pay for the energy transition. This can also lower the cost of capital.

The financial toolkit will need to be expanded with new instruments or new ways to deploy existing ones. Part of this new toolkit includes green and ESG bonds which have seen a recent surge in Latin America, albeit from low levels.

Climate change and the energy transition require a rethink of the roles of the state and the private sector in energy markets. The model based on SOEs has to be transformed into one of public-private partnerships. While SOEs and development banks can provide equity, debt and/or credit enhancements, it is the private sector that needs to take a leading role. Rather than extracting rents, the government needs to play a supporting role in these new industries. Innovators and private investors require credible local institutions, predictable regulation, and sensible market rules and pricing policies. All these instruments need longer term horizons, not linked to electoral cycles. Political experiments that lead to improvisation and polarization create uncertainty, and are completely at odds with what the energy transition needs.

What is at stake is whether countries in Latin America reap the benefits of the energy transition or bear only its costs.

—

Cárdenas is a senior research scholar at the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University. He was finance minister of Colombia from 2012-18.

Palacios is a senior research scholar at the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs.