Brazil | Colombia | Costa Rica | Mexico | Paraguay | Venezuela | Cuba

See above for a breakdown of the region’s other 2018 transitions, or click here for the full list from our print edition.

Election Date: October 7

Format: Two rounds. If no candidate receives more than 50 percent of votes in the first round, the two leading candidates will proceed to a run-off on October 28.

Geraldo Alckmin, 65, governor

Geraldo Alckmin, 65, governor

Brazilian Social Democracy Party

“Lula wants to return to the scene of the crime.”

How he got here: Alckmin began his career as a doctor, but has spent most of the last 17 years as governor of São Paulo, which accounts for a quarter of Brazil’s population and a third of its economy. His calling card, an 80 percent decline in the state’s homicide rate since he first took office, may resonate amid a national crime wave.

Why he might win: He’s an affable, somewhat bland figure who doesn’t inspire the kind of hatred (or love) most other Brazilian politicians do. If the economy is humming by October 2018 and enough voters want the status quo, he’d be a safe pick.

Why he might lose: He’s the leading establishment candidate in what still looks like a “Throw the bums out” election. Among leading candidates, Alckmin would fare worst against Lula in a runoff, according to a December poll. His low-key personality doesn’t play well outside the wealthier southeast.

Who supports him: Residents of São Paulo, business leaders, the “anybody but Lula” crowd for whom Bolsonaro is too extreme.

What he would do: Near-total continuation of President Michel Temer’s pro-business policies, with moderate to good support in Congress. Don’t expect a major reform or trade push, but a gradual attempt to shrink the state, streamline taxes and privatize.

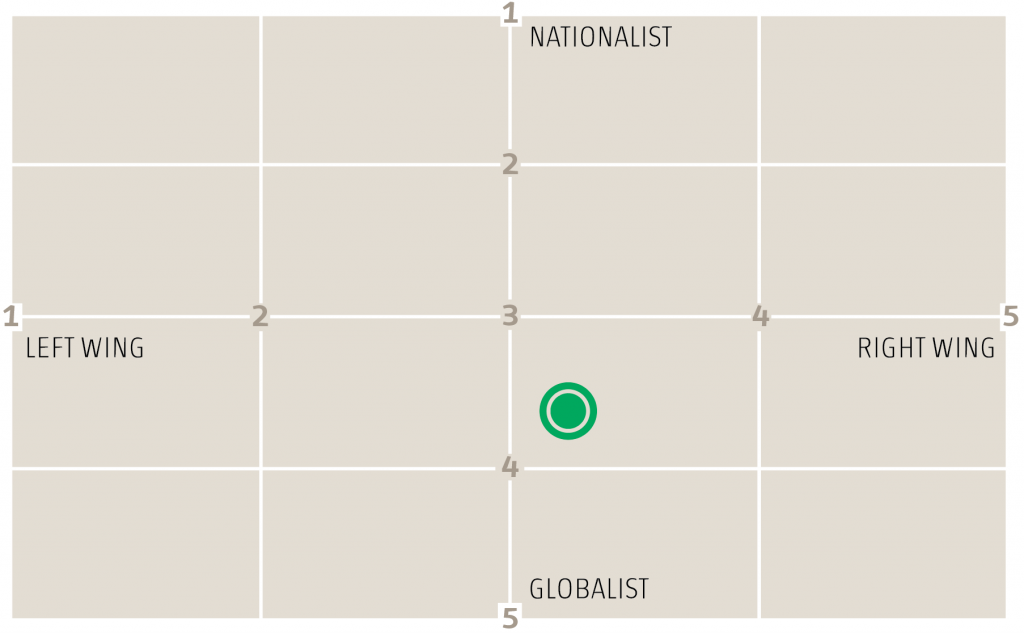

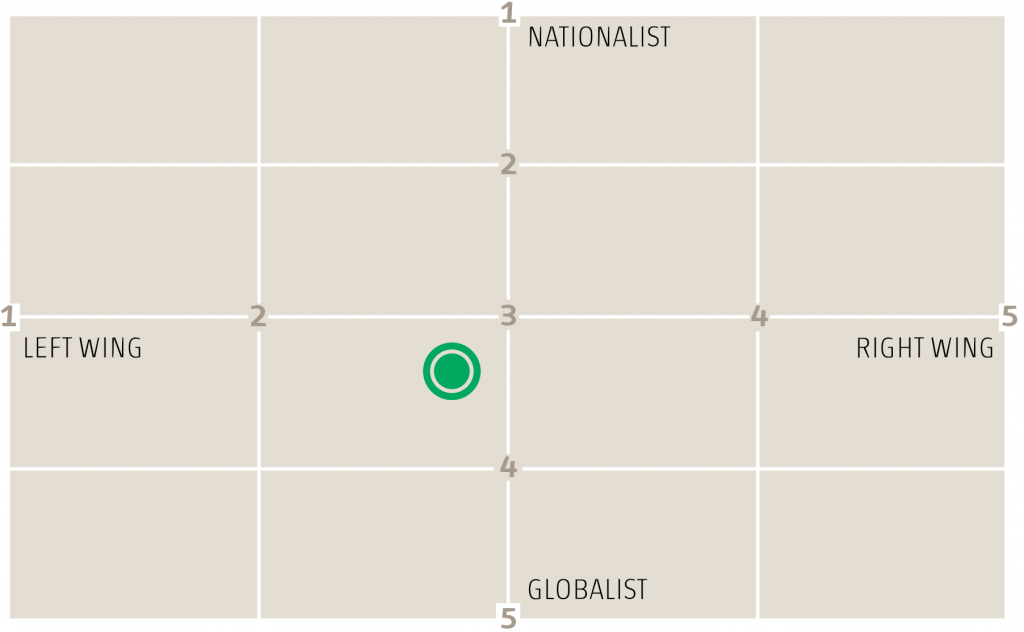

Ideology:

AQ asked a dozen nonpartisan experts on Latin America to help us identify where each candidate stands on two spectrums: left wing versus right wing, and nationalist versus globalist. We’ve published the average response, with a caveat: Platforms evolve, and so do candidates.

AQ asked a dozen nonpartisan experts on Latin America to help us identify where each candidate stands on two spectrums: left wing versus right wing, and nationalist versus globalist. We’ve published the average response, with a caveat: Platforms evolve, and so do candidates.

Jair Bolsonaro, 62, congressman

Jair Bolsonaro, 62, congressman

Progressive Party

“Brazil above everything, God above everyone.”

How he got here: A retired army captain and a congressman since 1991, Bolsonaro’s popularity abruptly soared during the 2014–2016 recession as Brazilians lashed out against corruption, rising crime and the existing establishment. His statements in favor of military rule, torture, and the right to bear arms, and against minorities and democratic convention, have endeared him to critics of political correctness.

Why he might win: His extreme law-and-order message carries tremendous appeal in a country with 19 of the world’s 50 most violent cities. He is one of just a few Brazilian politicians not facing corruption accusations. Avid, massive social media following.

Why he might lose: Brazil has a reputation, at least, as a tolerant, democratic country. Also, business leaders are skeptical of his self proclaimed conversion to market economics, and in a runoff would surely prefer Alckmin.

Who supports him: Bolsonaro is the leading candidate among Brazil’s wealthiest, best-educated voters, who are generally angriest about crime and corruption. Younger Brazilians, especially those age 18 to 25, are most likely to support him.

What he would do: He might try to concentrate power in the executive branch, but has no significant party support and might struggle to govern. After espousing a nationalist, protectionist agenda most of his career, Bolsonaro has rebranded himself as a business-friendly, small-government conservative.

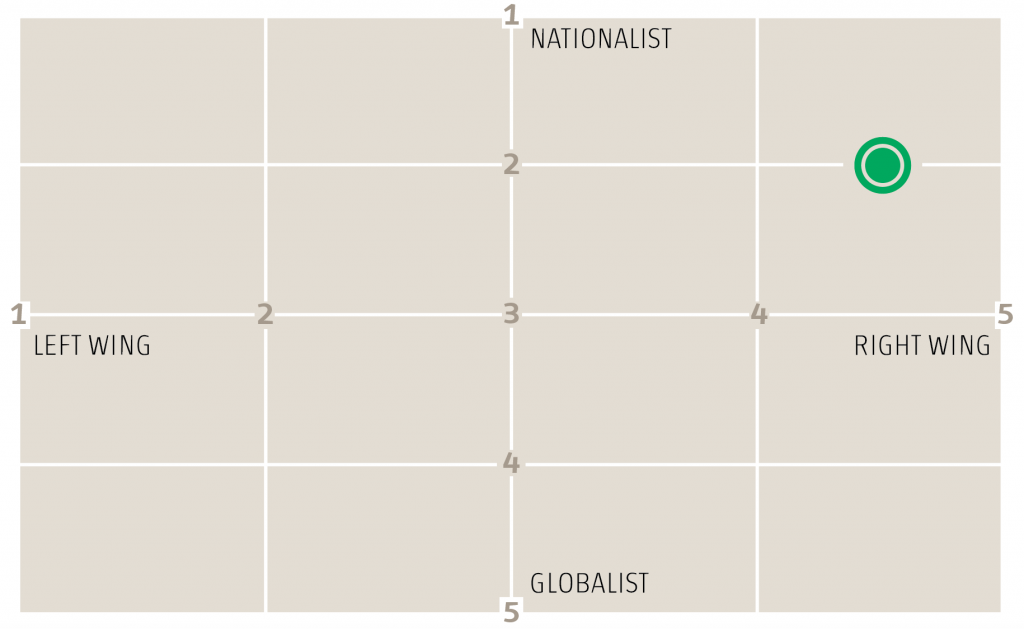

Ideology:

Lula Inácio Lula da Silva, 72, former president

Lula Inácio Lula da Silva, 72, former president

Workers’ Party

“In recent years, I have been the victim of a kind of massacre.”

How he got here: What a journey it has been. Lula was president from 2003 to 2010, and left on top with a booming economy and approval near 90 percent. Then the economy crashed, the Car Wash scandal erupted, and his chosen successor was impeached. More recently, some Brazilians have concluded Lula’s alleged crimes were less severe than others’ — and are ready to tolerate his sins if he brings back the glory days.

Why he might win: Lula has put his legendary charisma back to work, casting himself as a victim of political persecution by the Car Wash team. He can point to a robust record of poverty reduction and economic growth while president. He also has strong party support.

Why he might lose: His legal troubles could bar him from being a candidate — and he might even be in jail by election day. Bears significant, if not primary, responsibility for one of the worst recessions in Brazilian history. His lead in the polls might vanish as less-known rivals gain name recognition.

Who supports him: The poor, especially in Brazil’s northeast. But he has stronger support across social classes than many recognize.

What he would do: A question mark. Would he be the “Good Lula” of his first term (fiscal rigor, institution building) or the “Bad Lula” of his second (credit splurge, outlandish systemwide corruption)?

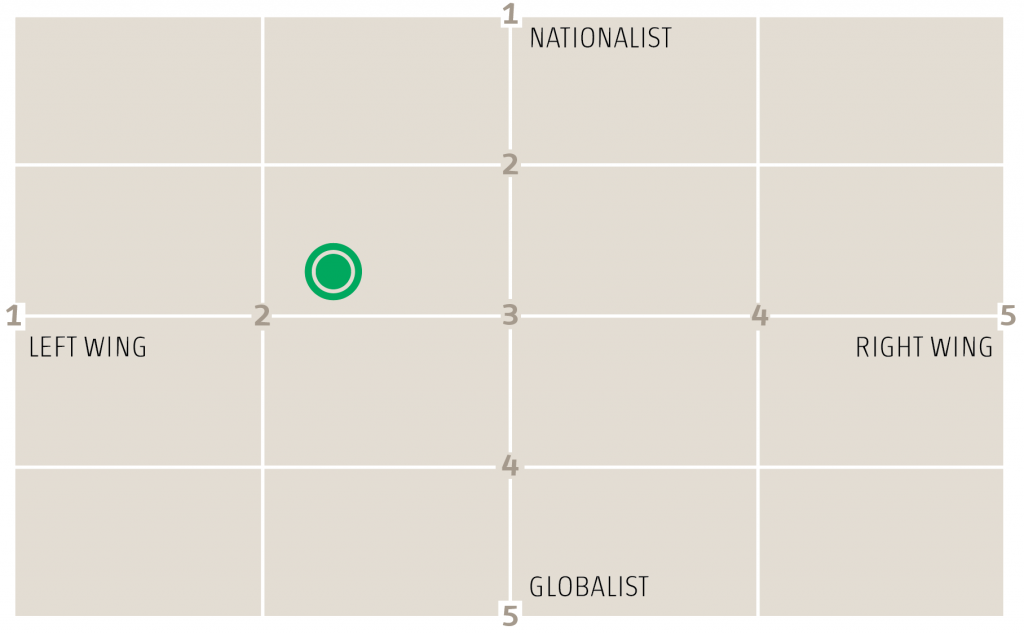

Ideology:

Ciro Gomes, 60, former governor

Ciro Gomes, 60, former governor

Democratic Labor Party

“Brazil is living at the margin of the law.”

How he got here: Gomes casts himself as an anti-establishment outsider, but he has held numerous political offices, including finance minister, governor, mayor and congressman. Will probably be the standard-bearer of Brazil’s left if Lula’s legal troubles prevent him from being a candidate.

Why he might win: A strong endorsement from Lula would make him an instant favorite to reach the runoff. Combines an interventionist economic platform with an uncompromising anti-corruption message. Has a decent power base and name recognition in the poorer northeast.

Why he might lose: His brainy, university lecture-style speeches go over a lot of Brazilians’ heads. It’s also not a slam dunk that Lula would endorse him; other possibilities include Fernando Haddad, the former São Paulo mayor, or former Bahia Governor Jacques Wagner.

Who supports him: Leftists, including those angry with the Workers’ Party. Older, better educated voters.

What he would do: Unrestrained by political convention or major donors, some observers believe Gomes would have the most radical economic platform in the race.

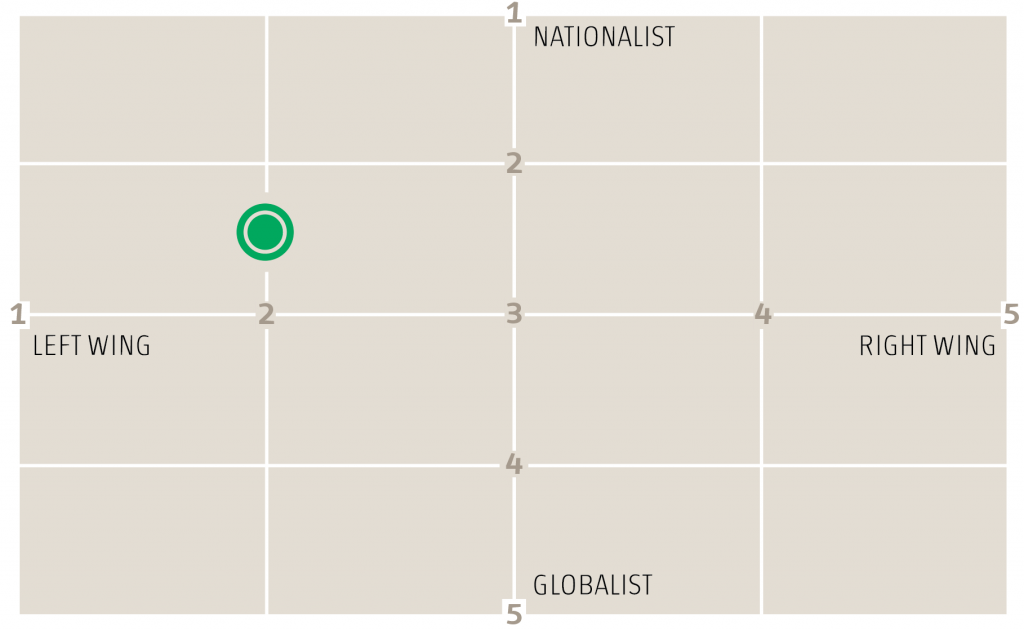

Ideology:

Marina Silva, 59, former senator and minister

Marina Silva, 59, former senator and minister

Sustainability Network

“I can’t win an election with a lie.”

How she got here: Escaped poverty, malaria and mercury poisoning growing up in the Amazon, learned how to read at 16, and transformed herself from a maid into a globally renowned environmentalist. Silva has run for president twice before, gathering about 20 percent of votes and missing out on the runoff both times.

Why she might win: Has one of Brazil’s most inspiring life stories. Her anti-corruption, anti-establishment message fits the moment. Combines social concern with a centrist economic platform.

Why she might lose: Even her biggest fans wonder if she has the physical stamina and coalition-building chops to be president. Staunch anti-Lula voters will never forgive her for serving in his government. Others feel her time has simply passed.

Who supports her: “Green” voters, business-friendly leftists, residents of medium cities and the lower-middle class. Her national name recognition trails only Lula’s.

What she would do: It’s unclear she could accomplish much with Congress, given her miniscule political party and embrace of principle over Brasília’s pork-barrel politics.

Ideology:

Mystery Outsider

Mystery Outsider

“You can be a rank insider as well as a rank outsider.” – Robert Frost

How he/she got here: Yes, there may still be room in this race for another candidate from outside the traditional world of politics. TV show host Luciano Huck ruled out a run in December, but some friends say he could still change his mind. Former Supreme Court Justice Joaquim Barbosa, who oversaw proceedings on graft in Lula’s government during the 2000s, could catch fire with an anti-corruption platform.

Why he/she might win: After years of recession and scandal, approval of traditional politicians has never been lower; one poll in December gave Congress just a 5 percent approval rating. Some believe candidates could enter the race as late as April.

Why he/she might lose: If there were a “savior” capable of running away with this race, he or she probably would have done so by now. Brazilians still remember how they elected a charismatic outsider as president in 1989. Fernando Collor de Mello froze bank deposits, tanked the economy and was ultimately impeached. Many angry voters will probably just spoil their ballots or not vote at all.

Who supports him/her: To be determined.

What he/she would do: Worth watching closely. Huck espouses a pro-business agenda, while Barbosa is a total wild card.

—