This article is adapted from AQ’s Top 5 list of Latin American art activists

As Daniel Arzola stood at an awards ceremony in New York last June, the theater broke into applause.

The actor Tituss Burgess had just recognized the 28-year-old illustrator for “creating change by creating art,” comparing his impact to that of the late designer of the gay pride flag, Gilbert Baker. One of Arzola’s idols, Cyndi Lauper, smiled from across the table.

“It was the most special and surreal night I’ve ever had,” recalled Arzola. “I told (Burgess) I was dreaming.”

But Arzola’s life hasn’t always been so glamorous. In fact, his work and identity have made him the target of such violence in his home country of Venezuela that he nearly stopped pursuing art.

When he was 15, neighbors in his hometown of Maracay attacked Arzola because he was gay. They tied him to an electric pole, removed his shoes and pants, burned him with cigarettes, and destroyed his drawings. They even threatened to set him on fire. Arzola had learned to draw before he could talk, but the trauma he suffered made him stop for six years.

“I realized how fragile the body is, and how fragile art is,” said Arzola.

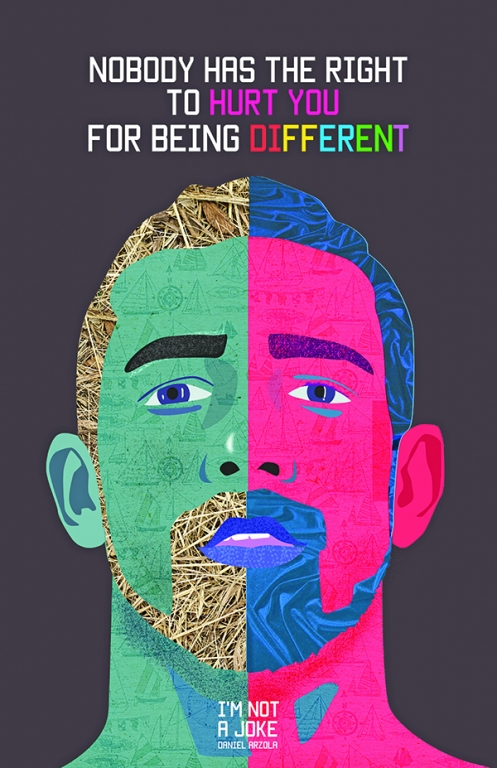

Arzola’s life changed when he discovered graphic design. By fusing drawing with technology, Arzola’s art became “indestructible.” He began to challenge bigotry and inspire LGBTQ people through his “artivismo.”

“(I hope that) someone can walk through a subway station in Buenos Aires and see my mural of a family with two fathers, and think, ‘Oh, there are people like me, I can have a normal life,’” he said.

Arzola’s breakthrough came in 2013 when Madonna retweeted his project “No Soy Tu Chiste” (I’m Not a Joke), and the illustrations celebrating gender and sexual diversity went viral.

The visibility came with a backlash. When he denounced the Venezuelan government’s homophobia, he began receiving death threats.

In response, Arzola moved abroad, eventually landing in Chile.

Looking back at the years after the hate crime, Arzola said he found an “example of bravery” in Federico García Lorca, thought to have been killed for his sexuality. It’s undeniable that Arzola has become a similar inspiration for many around the world.

—

O’Boyle is an editor of AQ.

A sample from Arzola’s “No Soy tu Chiste” project

A sample from Arzola’s “No Soy tu Chiste” project