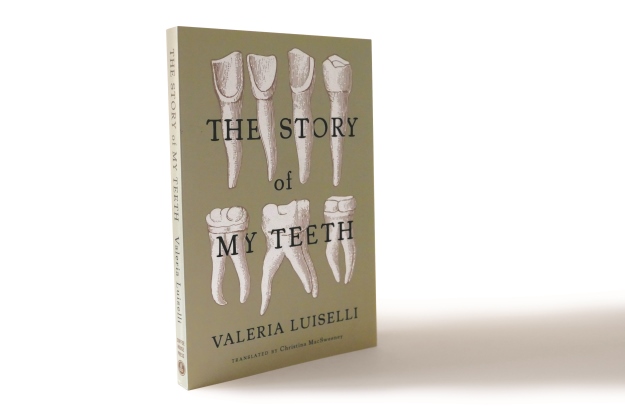

Reading Valeria Luiselli’s The Story of My Teeth (Coffee House Press) may provoke a vaguely familiar sensation for frequent readers of Latin American fiction — or, at least, a sense of recognizable unfamiliarity. Though Luiselli’s daring second novel is nothing if not refreshing, more than one reviewer has called the author “reminiscent of (Roberto) Bolaño,” navigating, as Diego Báez wrote for Booklist, “a dynamic, ghostly world between worlds, crisscrossing fact and fiction.” The comparison is not without merit.

The “world” of The Story of My Teeth is that of protagonist Gustavo “Highway” Sánchez Sánchez, an auctioneer who believes the stories we tell about objects – whether true, invented or somewhere in between – are more important than the objects themselves. In Highway’s case, the items in question are his own damaged, yellowed teeth, sold to unsuspecting bidders who, thanks to Highway’s persuasive fictions, believe they are purchasing teeth that once belonged to Montaigne, Rousseau, Virginia Woolf and others. Later, Highway does away with objects entirely, selling “allegories” – the stories of things that are all tied, in some way, to Mexican artists and writers.

I was thrilled to see a reference in one such story to Jorge Ibargüengoitia, a journalist, essayist and playwright, who died more than 30 years ago and whose work I discovered soon after moving to Mexico. Every essay in Ibargüengoitia’s book, Instrucciones para Vivir en México, was a gift that, unwrapped, presented another aspect of Mexico to me. Other readers may get the same thrill of recognition from seeing a reference to Francisco Goldman, a journalist and memoirist, or Guadalupe Nettel, herself a genre-spanning writer who, like Luiselli, has been inscribed on more than one “promising young writers to watch” list.

Luiselli’s many references to people, places and historical events will likely be obscure to those without a deep knowledge of Mexico and, in particular, the Mexican capital. That fact doesn’t seem to have bothered many critics, but it’s fair to ask what The Story of My Teeth will mean to readers who don’t recognize the many markers of Mexican cultural life.

Luiselli herself has addressed the question, explaining that she was curious about – even motivated by – the idea of context and recognition versus unfamiliarity when writing this book. In an interview with Stephen Sparks for The White Review, she described her conspicuous name-dropping as an effort to “explore how names modify the context into which they are placed, as well as how context reframes names.”

In the interview, she went on to categorize her novel as a “map (that) takes different readers to very different places, depending on what they bring to it.” The notion of novel-as-map is a useful one for looking not only at The Story of My Teeth itself, but also at how (and if) they use the novel — and products of popular culture generally – to “read” Latin America at large and Mexico in particular.

If her novel is a map, the route it will suggest for a reader who possesses few existing landmarks to Mexican culture will be quite different than that laid out for a reader with many, firmly planted ones.

But maybe those routes will all lead to a similar place – one of shared enjoyment, if not shared concerns about a particular place, a Mexico made more of fiction than of fact. The almost wholly positive critical reception of The Story of My Teeth suggests that we are headed toward a moment when aspects of another country’s place and history, once seemingly so insular, have become a sort of cultural creative commons. People, places and critical historical moments have always been, and perhaps will always be, decontextualized. By inserting them continuously into a broader global conversation, they get interpreted, as Highway’s teeth do, by people who may lack critical points of reference and even “the truth,” but who are invested in the story all the same.

—

Julie Schwietert Collazo (@collazoprojects) is a bilingual freelance journalist and writer who covers Latin America – especially Puerto Rico, Cuba and Mexico – and Latino/a USA for a vareity of publications. She has lived in San Juan and mExico Cityh and currently lives in New York City.