In June 2003, Brazil’s then-President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva found himself on the sidelines of a G8 summit in France, along with his counterparts from India and South Africa. They had been invited to the summit as observers, but the invitation served mostly to underscore a common frustration. “What is the use of being invited for dessert at the banquet of the powerful?” as Lula later put it. “We do not want to participate only to eat the dessert; we want to eat the main course, dessert and then coffee.”

This June, the leaders of the three countries will gather in New Delhi to mark the 10th anniversary of a group created to address that shared frustration. IBSA, as the group is called, was launched soon after the G8 summit with a modest-sounding announcement: as “three countries with vibrant democracies, from three regions of the developing world,” India, Brazil and South Africa (IBSA) had “decided to further intensify dialogue at all levels, when needed, to organize meetings of top officials and experts responsible for issues of mutual interest.”

Yet before long, the agenda became more sweeping, and the stated goals more ambitious. In 2004, the first communiqué issued by the three foreign ministers declared that IBSA would help “advance human development by promoting potential synergies among the members.” When President Lula hosted Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and then-South African President Thabo Mbeki for the first leaders’ summit in 2006, they hailed the coming of “a fair and equitable global order.” At the most recent leaders’ summit, in 2011, the joint statement proclaimed an IBSA mission to hasten “a new world order.”

These declarations have met with some skepticism, including in the IBSA countries themselves. Although no one doubts that the three countries can and should play a larger global role in the coming years, such statements leave many observers with a basic question: if IBSA is building a new world order, what exactly is that order supposed to look like?

But both that skepticism and the grandiose decrees that prompt it may miss the point. India, Brazil and South Africa are remarkable less for what they have managed to achieve globally than for what they are working to achieve domestically: proving the virtues of a model of democratic development that offers a stark contrast to the authoritarian capitalism of Russia and China, their partners in the brics. IBSA’s real value will depend on the extent to which it can help its members get this model of democratic development right—and make clear its virtues to the rest of the world.

A Seat at the Table

In its 10 years of existence as a “dialogue forum,” IBSA has produced a blizzard of memoranda of understanding and a proliferation of technical working groups on everything from education and trade to defense and Antarctic research. It has put forth common positions on central questions of international security and governance. It has held an IBSA Music and Dance Festival in Salvador, Brazil, replete with a choreographed rendition of the Mahabharata. Its leaders and foreign ministers have managed to gather at more or less regular intervals—no small accomplishment for any new grouping.

While the brics—which, since South Africa’s admission to the bloc, includes all three IBSA members, along with Russia and China—has drawn the headlines, some policymakers argue that shared democratic experience could give IBSA greater long-term potential. “Our heart is not in brics, but with IBSA. Common values matter,” a former top Indian official said privately. Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh has noted, “IBSA has a personality of its own […] bric is a conception devised by Goldman Sachs.” When the suggestion arose that China would lead an effort to subsume IBSA into the expanded brics, he shot back, “We should preserve the common principles and values we stand for.”

IBSA’s leaders have clear reasons for wanting this experiment in forging a new approach to South-South cooperation and global activism to succeed. In part, they see it as a way of projecting themselves into regions where they haven’t traditionally had much of a role. (In Brazil’s case, expanding its presence and nascent leadership in sub-Saharan Africa has become a central foreign policy tenet.) Perhaps more importantly, it could serve as a means of helping themselves win, to use Lula’s analogy, a real seat at the banquet of the powerful. “Better coordination,” Lula’s foreign minister, Celso Amorim, argued, “can improve our negotiating capacity and help build a multipolar world.” (Some political scientists point to this as an example of “soft balancing” against U.S. power.)

Soon after its formation, the IBSA countries led opposition to developed-world positions at the World Trade Organization (WTO) summit in Cancún, Mexico. In the process, Amorim gloated later, IBSA helped to create a developing-world bloc within the WTO that “played a decisive role in changing the negotiating model of the organization.” But their main objective—a regular focus of their discussions and communiqués—is reform of the UN Security Council. All three want a permanent seat on a new and expanded council, and they have pledged to push this case together, keeping reform (and their own places within it) on diplomatic and multilateral agendas.

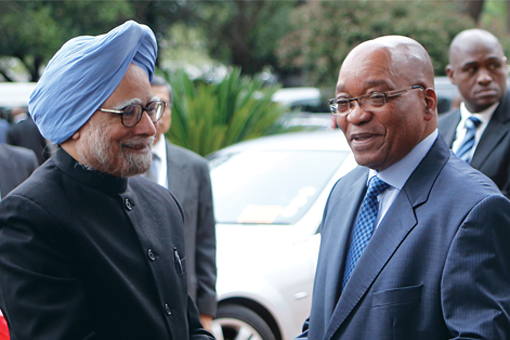

That made 2011 a particularly important year for IBSA. For the first time, all three nations held temporary seats at what remains the high table of global power. “The fact that the three countries currently participate in the Security Council,” said Amorim’s successor, Antonio Patriota, “is a circumstance that provides us with a particularly valuable platform at a time of momentous international events.” IBSA had already taken some steps to add a dimension of “strategic partnership” to its proceedings. In 2008, for example, the three navies started holding joint exercises off the coast of South Africa, an endeavor known as IBSAMAR. (South African President Jacob Zuma has proposed building on the exercises to add a “maritime security cooperation” dimension to IBSA.) Their overlapping terms in the rotating seats on the UN Security Council offered new opportunities to play a role on everything from the tumult in the Middle East to peacekeeping in South Sudan.

Most prominently and—in the eyes of some observers—provocatively, they sought an active role on Syria. As violence escalated, the IBSA countries saw it as their task to promote a third way between the interventionism of the Western powers and the intransigence of Russia and China. “As democracies,” one IBSA ambassador said, “we believed we had to try to help.” So, in August, they sent a high-level diplomatic delegation to Damascus. It met with President Bashar al-Assad and opposition representatives, heard the government’s promises of political reform, and hailed the virtues of diplomatic compromise and peaceful resolution. When the leaders met afterward, they celebrated the initiative. “The visit of an IBSA delegation to Damascus in August of this year and their interaction with the Syrian leadership demonstrated once again the political role which IBSA can usefully play,” Prime Minister Singh said. “We should build upon this unique experience.”

Yet bloodshed only grew worse after the IBSA delegation went home, and a peaceful diplomatic solution slipped further out of reach as Assad’s proclaimed commitment to peaceful reform looked increasingly implausible. When the IBSA members abstained on a Security Council vote on Syria, the human rights community chided them for placing their emphasis on nonintervention over their commitment to democracy and human rights. “By abstaining, India, Brazil and South Africa have failed the Syrian people and emboldened the Syrian government in its path of violence against them,” a Human Rights Watch representative said. “Their proclaimed distrust of the Western motives shouldn’t blind them into siding with an abusive government. Syria’s current behavior repudiates the very democratic ideals to which IBSA countries are committed.”

President Barack Obama’s first-term national security strategy emphasized the importance of “actively supporting the leadership of emerging democracies,” as part of a broader focus on “deepening our partnerships with emerging powers and encouraging them to play a greater role in strengthening international norms.” Some have argued that IBSA’s Security Council record demonstrates that this objective is misguided: Bruce Gilley, an American political scientist, has referred to IBSA as “a community of democracies from hell.”

IBSA officials counter, as one Indian official argued, that the developed powers “need to accept that we will do things differently than you, but that our approaches can be complementary.” They point to other examples in their Security Council record—supporting efforts in Cote d’Ivoire, for one—that offer some common ground for discussion. They have also endorsed and promoted the Brazilian concept of “Responsibility While Protecting.” RWP is a play on the Responsibility to Protect, or R2P, which helped drive Western actions in places like Libya—an intervention that, to IBSA, represented a misuse of humanitarian principles for regime-change ends. RWP reflects a traditionally zealous defense of sovereignty, but it is also a clear, if small, step away from dogmatic noninterventionism. While seeking to limit and qualify the international community’s right to intervene, it concedes that there are circumstances when intervention, done right, is appropriate.

An IBSA Model?

Delegations to conflict zones, visions of multipolarity and paeans to post-American multilateralism may draw the most attention, but IBSA’s more important work may in fact lie in more prosaic interactions—the efforts at promoting economic integration, the mid-level technical working groups, the small-scale trilateral cooperation, and the networks of academics, entrepreneurs and civil-society leaders that gather under IBSA’s people-to-people initiatives. India has sent officials to Brazil to study the success of Bolsa Familia as it looks to build its own system of conditional cash transfers. Brazil, in turn, has looked at South African policy toward wealthy taxpayers.

In 2003, for all their celebrations of comradeship and commonality—their diversity, their democracy, their developing-country status—total trade among the IBSA countries was less than $4 billion and connectivity of all kinds was low. Since then, trade has grown to close to $30 billion, with projections that it will approach $40 billion by 2015. Still, those figures must be put in perspective: India’s trade with China is about triple total IBSA trade, and Brazil’s is double.

Increased growth will require a more serious commitment to the stated goal of negotiating a trilateral free-trade agreement. “While each [country] has a large and diversified economy, with competitive agricultural, manufacturing and services trade profiles, they have also established distinct specializations,” the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development said in a 2007 study on the potential of an agreement. Such “complementarities,” it noted, could make IBSA “a key formation in the new geography of international trade.”

They have made more concrete progress on establishing an IBSA development fund, a new approach to South-South assistance that draws on their own experience as developing countries. As Lula has said, “With IBSA, we are proving that it is not necessary to be rich to show solidarity.” The three governments have made annual donations to the trilateral trust fund, which supports IBSA-branded development projects run by the UN Development Program. These have included everything from a waste-management facility in Haiti and health clinics in Burundi to a sports facility in the West Bank and the rehabilitation of a hospital in Gaza. So far, the contributions have been a relatively low $1 million each, but officials have discussed expanding the fund at the 10th anniversary summit this year.

All of this may sound distinctly unexciting amid the more grandiose claims of “strategic partnership” and “a new world order.” Yet it is such activities that will most powerfully reinforce the claim at IBSA’s heart: that democratic values can support rather than hinder development, and that their own records offer definitive proof that this is so. All three countries have crafted their own exemplary foreign policy doctrines around the power of this model of democratic development—positioning themselves as sources of expertise, inspiration and support for others.

To that end, the most important task for IBSA as it marks 10 years of existence is to prove that this model retains its appeal. For most of the past decade, the three countries have deservedly displayed a certain amount of triumphalism, thanks to rapid growth and impressive strides against poverty alongside a real commitment to democracy. When the global financial crisis started in 2008, they were right to chide the rich world for its recklessness, even when this chiding took on a self-satisfied air. But today, their future success is being widely questioned. All three are struggling with slowing growth, violence, corruption, and broad popular dissatisfaction. More than anything else, IBSA can prove its significance by helping its own members overcome these challenges—proving the viability of democratic development and the long-term virtues of the IBSA model.