This article is part of the Leaders of Social & Political Change series from the Fall 2012 issue of Americas Quarterly. View the full special section.

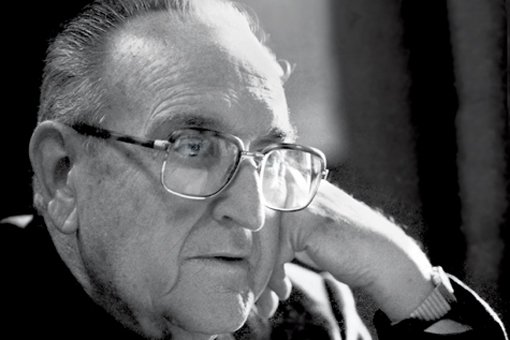

The 1998 assassination of Guatemalan Bishop Juan José Gerardi stunned a country ravaged by more than three decades of political violence. For four years, Gerardi had led an extraordinary effort by the Catholic Church to document the effects of a brutal government counterinsurgency campaign. His report, Guatemala: Never Again, was the synthesis of thousands of testimonies gathered from communities devastated by army massacres and aerial bombardment, kidnappings, rapes, torture, secret detentions, and public executions.

Although the conflict between the Guatemalan government and guerrilla forces had ended with the signing of a peace accord in December 1996, the extent of the human rights catastrophe caused by the civil war had yet to be acknowledged officially. Gerardi’s presentation of the report in the National Cathedral on April 24, 1998, was met with an outpouring of national grief and gratitude. Two days later, he was killed.

Ordained as a Catholic priest in 1946, Gerardi took his post of bishop in the northwest department of Quiché as persecution by government and paramilitary forces began to rise against members of the Church in the highlands. Bishop Gerardi’s parishioners were attacked and killed—most spectacularly when security forces assaulted the Spanish Embassy in January 1980, burning 37 people to death. On June 4, 1980, a priest serving under Gerardi, along with his sexton, were murdered. Gerardi went into exile weeks later and lived in Costa Rica, returning to Guatemala in 1982.

At the time, Guatemala remained gripped by savage conflict, and Gerardi was unable to resume his work in the highlands. Instead, he served as bishop to the San Sebastian parish in Guatemala City, and in 1989 founded the Archbishop’s Office of Human Rights of Guatemala, where he decided to launch an ambitious project to document the human rights atrocities that continued unabated. Called La Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica (The Recovery of Historical Memory—REMHI), the project’s innovation was in gathering direct testimony from survivors and eyewitnesses of the bloody conflict. In 1990, the organization received a grant from the Ford Foundation to support its work.

For the first time, the Mayan communities hardest hit by the repression were asked to give their own versions of how the army’s counterinsurgency campaign impacted their lives. The result was a compilation of shattering accounts of violence and suffering.

REMHI’s eloquence and impact reverberated throughout Guatemala and Latin America. It also prompted a swift and brutal response. Two days after Bishop Gerardi delivered his report, he was beaten to death in the garage of his parish home by murderers later linked to the Guatemalan army.

Astonishingly for a country infamous for its broken justice system, a group of men, including high-ranking army officers, was convicted for Gerardi’s murder some eight years after the crime.

Gerardi today is honored as Guatemala’s “martyr for truth,” and his legacy lives on—not only in his groundbreaking report, but in the transformative power of his vision, his life’s work and his ability in the end to carefully document the horrors of the past.