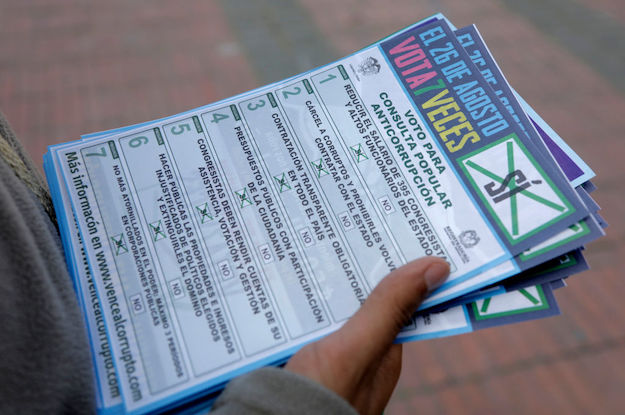

This article is adapted from AQ’s latest issue on Latin America’s anti-corruption movement.

Pérez Molina. Odebrecht. Keiko. They thought they were safe—until they weren’t. Public, high-profile arrests of some of Latin America’s most powerful figures have taken the struggle against corruption to new heights. But to get there, countries had to first adopt a number of instruments to combat and deter corruption. Below, AQ assesses 10 anti-corruption reforms and practices and, based on interviews with outside experts, offers a verdict on whether they really prevent corruption.

Corporate Liability | Plea Bargains | Campaign Finance | Int’l Collaboration

Term Limits | Asset Forfeiture | Attorneys General | Pre-Trial Detention

Open Procurement | Lobbying Rules

Corporate Liability Laws

What it looks like: Punishing companies for their employees’ corruption, usually through painful fines. Several Latin American countries have passed such legislation in order to comply with the OECD’s Anti-Bribery Convention.

Who tried it: The United States’ Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977 (FCPA) aims to prevent companies subject to U.S. jurisdiction from engaging in corruption overseas while doing business. It set a global standard for corporate liability legislation that countries in Latin America have followed to varying degrees.

Costa Rica and Chile were early adopters of this practice in the region, passing corporate liability laws in 2008 and 2009, respectively.

Brazil passed the Clean Companies Act in 2013, prohibiting not just bribes but also the offer or solicitation of a bribe from a public official or employee of a public company. The law incentivized the growth of compliance programs within private companies as well as cooperation with authorities.

Colombia passed the Transnational Bribery Act in 2016, establishing corporate administrative liability for bribes paid abroad, incentivizing compliance programs and creating a special agency that conducts bribery investigations and fines companies.

Passed in 2017, Argentina’s corporate liability law is one of the Macri administration’s key accomplishments on the anti-corruption front.

Results: Corporate liability in Latin America is still in its early stages and doubts remain regarding countries’ capacity and will to enforce these new laws. Yet they can become a powerful instrument to punish and deter corruption, much like the FCPA in the U.S. Also, such legislation directly contributes to the promotion of compliance cultures. For example, Brazil’s 2013 law paved the way for the Public Companies Act in 2016, which set guidelines for corporate compliance programs in state-owned companies.

Does It Work?

Plea Bargains and Whistleblower Protections

What they look like: Plea bargains provide suspects with lighter or no sentencing in exchange for cooperation in investigations. Similarly, whistleblower protections provide options for employees to report corruption within their organization or company with a lesser threat of legal repercussions.

Who tried it: Brazil’s 2013 Organized Crime Law significantly expanded plea bargaining, which became an indispensable prosecutorial tool for Lava Jato and other major anti-corruption operations since. The new law gave prosecutors and police the power to negotiate defendants’ collaboration in exchange for partial or full immunity.

In February, Peru signed a plea deal with Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht, which agreed to pay some $200 million in fines and assist investigations into its criminal activity in Peru. In exchange, prosecutors agreed not to go after individual executives and to let Odebrecht continue operating in the country.

Chile passed a whistleblower law in 2007 requiring employees to disclose wrongdoing within public administration.

In 2017, Argentina passed whistleblower legislation offering reduced sentences to suspects who provide information on high-level figures in criminal structures.

Results: Though controversial because of the perception that they let criminals off the hook, plea bargains have helped reveal the extent of regional corruption. It was through a plea deal with U.S., Brazilian and Swiss prosecutors that Odebrecht first admitted to paying nearly $800 million in bribes across Latin America and in Africa. In Argentina, meanwhile, plea bargain rules have limitations that undermine efficiency. They can’t be used to uncover new cases and minor sentences can be reduced by half only if a judge finds their confession helpful. However, many still credit the whistleblower law for the development of investigations surrounding the Notebooks case.

Does it work?

Stricter Campaign Finance Rules

What it looks like: Stricter limits on who funds campaigns—and the way they do so—in an effort to level the playing field and get dirty money out of politics. Efforts to curtail the length of campaigns, for example, can keep costs down, which some believe helps reduce dubious transactions.

Who tried it:

Argentina barred campaign donations from businesses in 2009. The country overturned the ban in 2019 in a reform package that also prohibited cash contributions.

After a spate of scandals, Chile barred corporate campaign donations in 2016 in addition to better regulating individual contributions.

Like Chile, Brazil barred businesses from supporting campaigns in the fallout from revelations of Odebrecht’s massive kickback scheme. Brazil also reduced the length of campaigns from around five months to three months.

Results: Most experts and transparency activists agree democracy isn’t cheap. But there’s less agreement on what an ideal campaign financing framework looks like. Questions abound, for example, over how to curtail or regulate the influence businesses can have by funding campaigns. After Argentina barred corporate donations in 2009, they didn’t really stop—they just happened under the table. That became clear after the Notebooks scandal in 2018, which prompted a new reform to allow such contributions in the hope they could be regulated. In Brazil, there have been concerns that businesses have continued financing politics through individual employees or stakeholders, making it more difficult for observers to see which interests are funding campaigns.

Does it work?

International Collaboration

What it looks like:

Efforts between countries to form what the Inter-American Development Bank calls “collaborative mechanisms” for detecting and prosecuting corruption. These can be country-specific initiatives, like the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), or broader collaboration around truly transnational issues like extradition and money laundering.

Who tried it: In 1996, Latin America set a global precedent when member nations of the Organization of American States (OAS) signed the Inter-American Convention Against Corruption – the first international accord of its kind.

Guatemala signed an agreement with the UN to create CICIG in 2006. The partnership brought funding, expertise and independence to Guatemala’s corruption investigations.

Inspired by CICIG, the OAS worked with Honduras to establish the Mission to Support the Fight against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (MACCIH) in 2016.

Brazil passed its bilateral treaty on mutual legal assistance with the U.S. in 1998. Its subsequent collaboration with the U.S. Department of Justice, as with governments in countries like Switzerland and Peru, has been critical to the evolution of Lava Jato.

Results: International partnerships bear fruit when implemented well. Brazil’s partnership with the U.S. on Lava Jato, for example, led to multinationals paying more than $1.9 billion in penalties to the U.S. and nearly $4.4 billion to Brazil. In Guatemala, CICIG helped secure hundreds of convictions and helped unseat then-President Otto Pérez Molina. The political class eventually rebelled, and President Jimmy Morales announced CICIG’s mandate would end in 2019. MACCIH, whose partnership with the public prosecutor’s office helped implicate dozens of legislators and a former first lady, also faces political resistance. Such blowback reflects the challenges these partnerships face in being sustainable. Still, both boast positive track records and have inspired presidents in Ecuador and El Salvador to pursue similar initiatives.

Does it work?

Term Limits and Re-election Bans

What it looks like: Term limits and reelection bans intended to stop elected officials from working with the ultimate goal of winning reelection and using public service as a path to wealth. While reelection rules across the region have become more permissive over the last 25 years, recently movements to ban reelection have gathered steam in the aftermath of high-profile corruption scandals.

Who tried it: Colombia banned presidential reelection in 2015 after permitting it a decade prior.

In 2016, Bolivians said no to presidential reelection in a referendum called by President Evo Morales—who is running for a fourth term this year regardless.

In a 2018 referendum, Ecuador reversed former President Rafael Correa’s law allowing unlimited presidential reelection.

In another referendum last year, voters in Peru approved a constitutional reform to end consecutive reelection of members of Congress, similar to a standing prohibition banning consecutive presidential terms.

While Mexico recently allowed reelection for legislators and mayors, it remains prohibited at the presidential level.

In June, Chilean lawmakers began debating reforms that would limit reelection for public officials.

Results: While politicians are likely presented more opportunities for bad behavior the longer they are in office, there is little evidence to suggest that term limits in themselves curb corruption. Thus, recent decisions in Colombia, Peru and Ecuador may in time serve as telling case studies. Mexican history shows that a one-term presidency rule cannot significantly deter corruption in the executive branch. There is a direct relationship between a total lack of term limits, as is the case in Venezuela and Nicaragua, and the weakening of democratic institutions and rule of law.

Does it work?

Asset Forfeiture

What it looks like: This practice of seizing assets derived from corruption or used to funnel dirty money aims to provide compensation for the victim, which is most often the state. The other end goal is to cut off financing to organized crime and disincentivize corruption.

Who tried it: Colombia was first in the region to implement an asset forfeiture law in 1996.

Like several countries in the region, Guatemala began updating its asset recovery legislation to come in line with global standards after the financial crisis. The 2010 asset forfeiture law, which allowed the public ministry to seize properties bought with illicit money, proved a powerful tool in fighting organized crime.

In Mexico, Congress passed reforms that will allow for the expansion of a 2009 asset seizure law to include corruption cases. Meanwhile, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has launched an agency to auction confiscated goods in order to fund social spending.

In Argentina, Macri issued a decree in January to recover assets seized through corruption-related crimes, as well as drug trafficking and other crimes.

Results: Bureaucracy often impedes optimal implementation of asset seizure laws. There are also inherent risks in cases where assets are returned to a state that is presumably corrupt. Questions over due process and over the morality of seizures also arise. For example, when the Honduran government seized the companies of a businessman under indictment and sanctioned by the U.S. for drug trafficking—but with no conviction—thousands lost their jobs. Nevertheless, experts say asset recovery mechanisms are essential for dismantling corruption networks.

Does it work?

Rules to Pick Attorneys General

What it looks like: Selection and nomination processes designed to limit a head of state’s ability to appoint chief prosecutors without oversight. In some cases this means dividing responsibility for nomination among different branches of government, while in others oversight or nomination authority is given to technical committees made up in whole or in part by experts in law and judicial systems.

Who tried it: Brazil has a de facto practice for selecting chief prosecutors: members of the Public Ministry elect a “triple list” for the position and the president picks one of the three names. The practice, however, is not written in law.

In Mexico, recent reforms have enforced additional steps to nomination: the Senate comes up with a list of 10 candidates from which the president selects three finalists. That list of three is sent back to the Senate for a final vote.

Aspiring attorneys general in Guatemala apply and are interviewed by a judicial selection committee, which sends a list of six finalists to the president to choose from.

In Colombia, it’s the Supreme Court that makes a final selection based on the president’s list of three finalists.

Results: While these procedures can provide a check on executive authority, the result isn’t always a truly independent prosecutor. In Mexico, Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s majority in the Senate made it all but certain that his preferred pick for the post would be selected. Critics in Guatemala say that the technical committee is vulnerable to political maneuvering: the number of law schools in the country grew from four to 12 after the nominating procedure, which guarantees law school deans a spot on the committee, was created. Before resigning his post in May, ostensibly over an unrelated issue, Colombia’s then-Attorney General Néstor Humberto Martínez was accused of personal involvement in the Odebrecht corruption scandal.

Does it work?

Pre-Trial Detention

What it looks like: A common practice across Latin America, the detention of individuals before any indictments or trials has been increasingly applied to high-profile individuals accused of corruption. Usually these detentions are authorized due to flight risks, evidence of obstruction of justice or the suspicion of ongoing criminal activity.

Who tried it: Brazilian authorities have systematically used pre-trial detention in the context of anti-corruption investigations—including twice against former President Michel Temer. Analysts agree that pre-trial arrests have been used to increase the pressure on defendants to sign collaboration deals, sometimes raising questions about abuses and judicial overreach.

Peru: Authorities have placed numerous prominent politicians including former presidents in pre-trial detention for alleged corruption. In April, former President Alan García committed suicide after police arrived at his home to arrest him. The tragedy sparked a national debate about the legality of such arrests.

Argentina: A judge has requested pre-trial detention for former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner in relation to several corruption indictments. As a senator, she has immunity from arrest. Others allegedly involved in Argentina’s Notebooks scandal have not been as lucky.

Results: Pre-trial arrests have been key to sending powerful figures to prison, reducing the perception of impunity for corruption crimes. They have also provided a useful opportunity to question suspects and obtain information. However, public outcry over some cases—such as García’s in Peru—has fueled accusations of prosecutorial overreach. There are also concerns of adding to an overcrowding problem: Individuals in pre-trial detention accounted for 36% of the hemisphere’s prison population in 2016.

Does it work?

Open Procurement Processes

What it looks like: Accessible data on public tenders—often online—aims to promote transparency in contracting. Opaque processes for contracting goods and services have facilitated widespread corruption in Latin America, particularly in the infrastructure sector, including rigged bids, bribes to secure projects and padded contracts.

Who tried it: In 1997, Mexico launched CompraNet, a national e-procurement system that logs public tenders made electronically. Mexico City introduced Contrataciones Abiertas in 2016, a web portal that provides free access to the city’s public spending and contracts.

ChileCompra is an online platform that provides information on all public contracts in the country and operates Mercado Público, a website where Chilean public entities publish their contracts and providers offer products and services to the government.

Colombia Compra Eficiente is a transparent e-procurement platform where users can find data on public purchases as well as carry out transactions with the government.

Open contracting data in Paraguay is available online through the National Directorate of Public Procurement, which also runs ¿Qué Compramos?, a website that provides access to data and visualizations of state purchases.

Results: These open data platforms have created more transparency surrounding public procurement by making data available to the private sector, journalists, government watchdogs and the public at large. However, critics point to a lack of modernization and incomplete reporting on these platforms. For example, ChileCompra does not include information about renegotiated contracts, whose amendments are not available to the public. Platforms in some other countries are often so confusing as to be practically useless.

Does it work?

Stricter Lobbying Rules

What it looks like: Lobbying has largely gone unregulated in Latin America. The few lobbying rules in the region are also weakly enforced, leading to an opportunity for corruption in this crucial interaction between public and private sectors.

Who tried it: In 2003, Peru became the first Latin American country to pass a lobbying law, which applies to the legislative and executive branches in the national and local governments. The law bans lobbying for all public officials for one year after they leave their posts.

Mexico: A 2010 lobbying regulation covers only the legislative branch, requiring a registry of lobbyists active in Congress.

Argentina: A presidential decree from 2003 regulates lobbying in the executive branch, but the rule to register meetings with lobbyists is rarely followed.

After ten years of parliamentary debate, Chile’s congress passed a law in 2014 that regulates lobbying in the legislative and executive branches, as well as at the regional and local level. The Chilean government’s Transparency Council also operates Infolobby, an open-access website that contains a range of lobbying information, from meetings to travel and gifts.

Results: Regulating lobbyists is critical for reducing corruption, but rules that are bad or not enforced don’t change much. In the U.S., for example, regulation largely legalizes what’s already common. In Latin America, legislation is undermined by underreporting or poor compliance. Peru’s requirement for lobbyists to report on their activity every six months deterred many from even registering. In Chile, the region’s most comprehensive lobbying legislation functions more as a transparency mechanism than as a law that regulates the lobbying industry. The same applies to Argentina. Government officials disclose inconsistent information on lobbying activity, oversight is difficult, and sanctions are rarely enforced.

Does it work?