This article is adapted from AQ’s print issue on how to make Latin American cities better. Click here to see the rest of our Top 5. | Leer en español

SÃO PAULO – Even by the hazardous standards of big Latin American cities, cycling in São Paulo can be a matter of life and death.

In 2009, Márcia Prado, who had advocated for greater rights for cyclists, was pedaling to work on Avenida Paulista, the city’s main thoroughfare. A bus cut Prado off, touching her bike’s handle. She fell and was crushed by the bus’s rear tire, joining a ghastly death toll that last year hit 61 fatalities.

The tragedy struck a chord with Aline Cavalcante, who at the time was a 23-year-old graduate student. She was just starting to venture out on her bike after moving to São Paulo from the smaller northeastern city of Aracaju. “If someone with that much experience died, I was very vulnerable,” she remembers thinking.

With its pleasant climate, and some of the world’s worst traffic jams — the average citizen spends about three hours in traffic daily — conventional logic suggests that São Paulo would be a more bicycle-friendly city. Yet only about 1 percent of paulistanos, as residents are called, say they use bikes as their main form of transportation. A quarter use cars, while another 48 percent travel daily by bus.

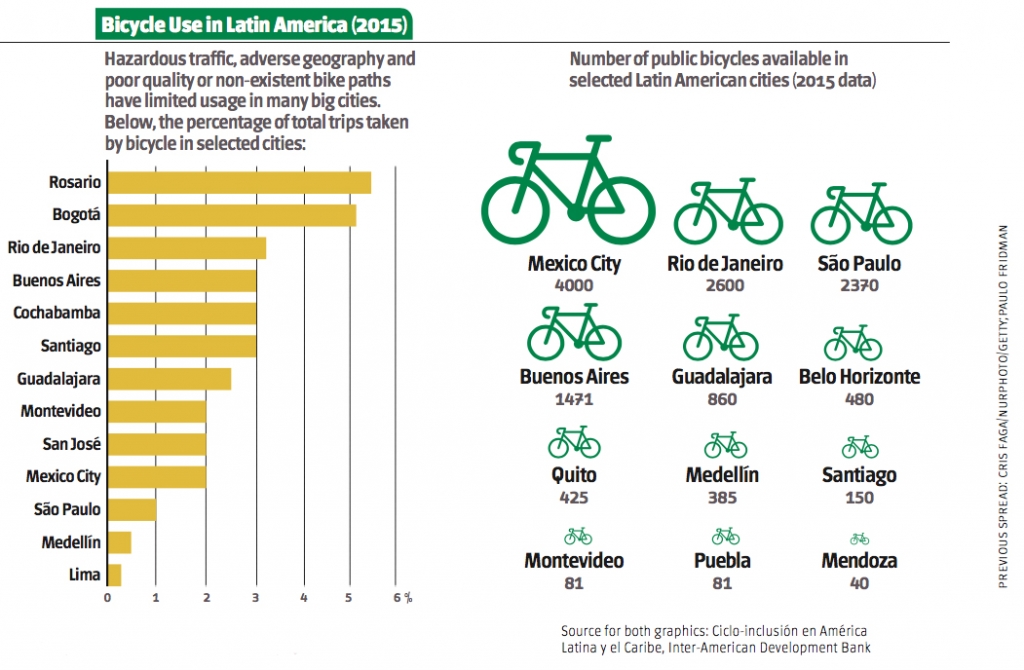

The problem is partly geographic — the city sprawls and is very hilly in parts — but attitudes and infrastructure are also big impediments. Cyclists routinely endure verbal abuse, buses and cars that creep into their space, and a chronic shortage of dedicated bike lanes. The result: A 2015 research paper by the Inter-American Development Bank concluded São Paulo was the fourth most deadly for cyclists among 18 Latin American cities. Its rate for cycling deaths, 0.7 per 100,000 residents, was ten times higher than Mexico City’s.

More: Why Reducing Reliance on Cars Won’t Be Easy

But people like Cavalcante are working to change that — and have produced encouraging results. Galvanized by Prado’s death, that same year she joined other activists to found Ciclocidade, an association of cyclists. Since then she has become one of the best-known and most vocal bike activists in Brazil. Last year, she delivered a manifesto on mobility to the executive secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Patricia Espinosa. She also runs an advocacy project focused on climate change and mobility.

“People think bikes are for leisure activities,” she said. “They don’t think they can use them during the week to go to work.”

Ciclocidade now serves as a powerful channel between government officials and cyclists, proposing and negotiating policy in partnership with other associations in the city. They also run group studies and surveys about key issues and do public service announcements.

As the advocacy lead, Cavalcante is also a pragmatist, willing to make concessions to achieve bigger goals.

“She packs big punches with kid gloves,” said Renata Falzoni, a bike activist since the 1970s. She said the new generation Ciclocidade represents “has research, data, they have coherence in their speech. My generation didn’t have any of that.”

The city’s cycling infrastructure began to improve in 2013 — sadly, because of another accident.

A cyclist named David Santos had his arm severed when he was hit by a car. A protest erupted, and Cavalcante joined a 200-strong crowd that went to the doorstep of the then-mayor, Fernando Haddad, to demand change and an opportunity to press their case.

At 6:30 a.m. the following Tuesday, Cavalcante got a meeting with Haddad. It was the beginning of a partnership that revolutionized the city. Haddad’s administration would build 250 additional miles of bike lanes, compared to just nine miles that existed when Ciclocidade was founded in 2009. A special council for cyclists to discuss policy with city officials was created. Activists even starred in the government’s awareness campaigns on cyclists’ rights.

“That protest was decisive,” said Suzana Nogueira, who used to coordinate cycling projects for the São Paulo municipal body charged with improving traffic flow. “Up until then, (the government’s proposals) weren’t concrete.”

In what was perhaps the highlight of his administration, Haddad decided to shut down Avenida Paulista, where Prado was killed, to road traffic on Sundays. There was much upheaval among shop owners, who said customers wouldn’t be able to reach them. Ciclocidade members made an effort to explain to them that the new policy would be great for business. When Paulista became a major thoroughfare for bicycles and pedestrians, it turned out the activsts were right.

“Now they love us,” said Cavalcante.

Haddad’s bike-friendly policy became an international story. The New York Times called it “urban shock treatment,” The Economist wrote that São Paulo was the “Tropic of Copenhagen.”

São Paulo’s then-mayor Fernando Haddad in 2014

São Paulo’s then-mayor Fernando Haddad in 2014

Cavalcante became a lead character in the award-winning documentary Bikes versus Cars. Until the film came out, she didn’t realize “how much my work really had an impact,” she said. “We changed this city.”

There was a backlash: Some of the bicycle paths were poorly planned. Haddad also lowered the city’s speed limit, and many motorists began associating the bicycling movement with a slower pace of traffic on some roads, even though congestion improved overall. The mayor’s popularity also suffered because he was a member of the Workers’ Party, which governed Brazil at the time and led it into a disastrous recession in 2015.

When Haddad ran for reelection in 2016, he lost to João Doria, a businessman from the more conservative Brazilian Social Democratic Party. Doria’s campaign slogan was “Accelerate São Paulo.” He raised the speed limit again, and no new bike lanes were built.

So now the challenge for Cavalcante and others is to get progress moving again.

The 2015 Inter-American Development Bank study showed only 1 percent of trips were taken by bike in the city, compared to 5 percent in Bogotá and 3 percent in Buenos Aires. São Paulo’s new Mayor Bruno Covas (Doria resigned in April to run for governor) launched a plan in August proposing more than 850 additional miles of bike lanes in the next decade. New bikesharing programs have also been announced.

But Cavalcante wasn’t optimistic. Days before the plan was announced, she and more than 20 other activists attended a bike council meeting with city officials. They complained about not being invited to contribute to the new plan before it was publicized.

Once again, their activism won them an audience with the mayor. Following the meeting with Covas, Cavalcante said she felt confident. “We demonstrated strength, coherence and a will to contribute,” she said. “Now we have to keep the pressure on.

—

Andreoni is a journalist based in Rio de Janeiro