This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on COP30

SANTIAGO—The half-century arc of SQM reads like a tale of modern Chile. Self-proclaimed heir to a bygone saltpeter boom in the Atacama Desert, the mining company has evolved from state control to privatization, from political controversy to corporate savvy, from insular vision to global reach.

Today, the trajectory of Sociedad Química y Minera de Chile S.A. (SQM)—the world’s second-biggest lithium miner — is intertwined with Chile’s stop-and-start campaign to mine more of the critical mineral used in batteries for electric vehicles (EVs) and renewable energy storage. Chile became the second-largest producing country after policy fumbles in recent years ceded the top spot to Australia. And newcomer Argentina, now considered a friendlier investment destination, is nipping at Chile’s heels.

To shore up its market edge at a time of geopolitical turmoil, SQM is staking its future on a once unthinkable long-term partnership with Chile’s state-owned copper mining company Codelco. But the preliminary public-private deal, signed in May 2024 after direct negotiations rather than a tender, is facing growing scrutiny ahead of Chile’s elections in November.

Outgoing President Gabriel Boric is betting that Codelco’s tie-up with SQM will accelerate Chile’s lithium production, boost government revenue, impose a degree of state control over the coveted resource, transfer technological know-how, and improve sustainability as concerns over water use mount.

Detractors argue that the Codelco-SQM deal lacks transparency, and that Chile could capture more rent with a competitive tender and by authorizing concessions that leave lithium mining in more experienced and efficient private-sector hands. For others, especially among Boric’s own left-wing base, SQM—or “Soquimich,” as it is commonly known—is an irredeemably tainted partner.

A checkered past

Founded in 1968 as a public-private venture under state development agency Corfo, SQM was privatized in the 1980s during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, when his then-son-in-law, Julio Ponce Lerou, came to control the company through a series of sweetheart transactions.

Ponce Lerou had himself headed Corfo until 1983, and was forced to resign amid allegations of corruption, which he denied. Other scandals would dog him and SQM long after Chile restored democracy in 1990. In the 2010s, heavy fines for a sweeping insider trading scheme were followed by a blow-up over systematic illicit financing of politicians, for which the company paid over $30 million for violating the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA). (Ponce Lerou denies wrongdoing.)

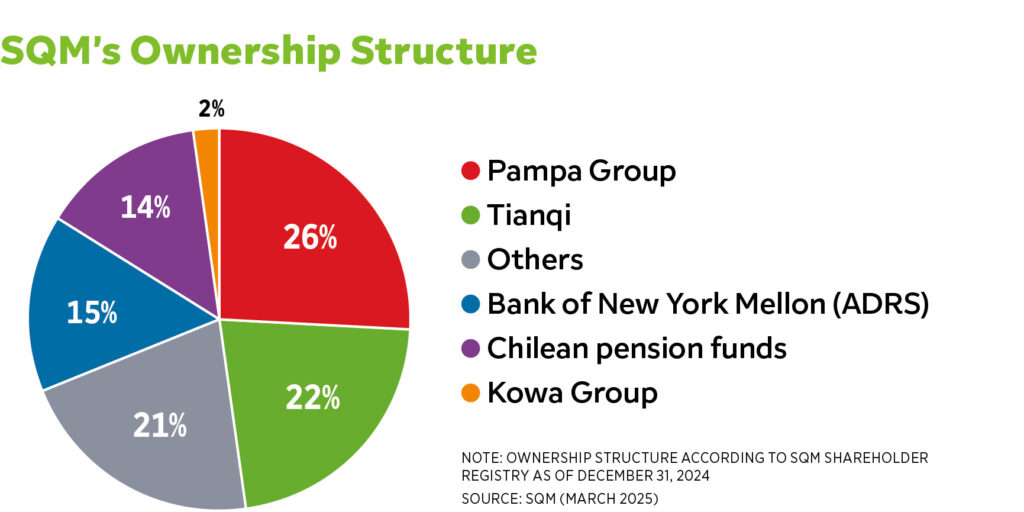

Chilean legal proceedings are ongoing. Today, the reclusive 79-year-old is consolidating his enterprise Grupo Pampa, which remains SQM’s largest shareholder with a 26% stake, and has passed leadership to his daughter, Francisca Ponce Pinochet. Upon announcing the changes, Ponce defended his tenure at SQM from “myths, criticisms and controversies.” Still, SQM’s joint venture with Codelco would bar him and his close relatives from any future managerial role.

Despite its checkered past, SQM ranks among Chile’s top enterprises, with a market capitalization of around $9 billion. The firm “has organized itself over many decades to squeeze everything, including the pips, out of the lemon,” London-based mining consultant Christopher Ecclestone told AQ. This has enabled it to compete with U.S.-based Albemarle Corporation—the world’s largest lithium producer that operates beside SQM in the shimmering high-altitude Salar de Atacama salt flat. And more competition is coming to northern Chile; Anglo-Australian mining giant Rio Tinto has just partnered with Codelco and smaller state-owned company Enami in other lithium-rich salt flats.

Supply surge

SQM’s portfolio is robust; lithium accounted for nearly half of the company’s total $4.5 billion in revenue last year, but iodine and fertilizers represented 21% apiece. Already the world’s top producer of iodine, SQM is building a new seawater pipeline in Chile to boost output as prices climb.

This softened the blow as lithium prices plummeted from over $80,000 per ton in late 2022 to around $9,000 today, reflecting persistent oversupply. After posting a profit of over $2 billion in 2023, the company saw a net loss of $404 million last year. Management attributed part of that 2024 loss to a one-time tax bill exceeding $1 billion.

In the first quarter of this year, SQM posted a lower-than-expected net profit of $138 million—compared to a loss of $870 million in the first quarter of 2024—as it upped its lithium sales volume 27% to compensate for a corresponding decline in the company’s average sales price. Management has warned of even softer prices in the second quarter.

In Chile, SQM plans to expand production of lithium hydroxide from a current 35,000 metric tons (MT) to 100,000 MT by the end of the year and lithium carbonate from 185,000 MT to 240,000 MT in 2026.

On a quarterly earnings call in May, this pedal-to-the-metal supply strategy prompted Joel Jackson of BMO Capital Markets to ask, “Don’t you get worried that your view on supply could be wrong?” Over the long term “oversupply will disappear,” SQM lithium manager Carlos Díaz responded. “There’s no way the industry can survive these prices,” added CEO Ricardo Ramos, asserting that SQM, which has “by far the lowest cost” in the industry, is prepared to meet global appetite once prices bounce back. In March, the company slashed its 2025 capital spending plan 31% to $1.1 billion.

Overseas, SQM is ramping up a new lithium hydroxide joint venture in Australia, where the mineral is more costly to mine. “For SQM to grow more in Chile was practically impossible,” Santiago-based lithium consultant Daniel Jiménez told AQ. Chile has rigid production quotas, a legacy of the 1970s when lithium was erroneously believed to hold strategic nuclear applications. Bizarrely, these quotas still require approval from Chile’s nuclear energy commission. This outdated framework, together with permitting delays, hinders investment.

State bargain

When Boric took office in March 2022, lithium prices were skyrocketing. To seize the opportunity missed by his predecessor, late President Sebastián Piñera, he proposed a National Lithium Company, but the idea soon tanked along with a constitutional draft that would have enshrined it.

Then, in 2023, Boric unveiled a National Lithium Strategy to double lithium production in 10 years. The cornerstone was a government offer to SQM that was hard for the boardroom to refuse: partner with Codelco or risk losing its lithium operations after 2030, when its current Corfo contracts expire.

Under the terms of the deal, which is expected to close later this year, SQM will partner with Codelco in 2025-30, and from 2031-60, Codelco will take control of the venture with a 50% stake plus one symbolic share.

After the initial handshake agreement in December 2023, Piñera’s former Mining and Energy Minister Juan Carlos Jobet described it as pragmatic and “politically astute.” But sentiment has since hardened. Chile’s center-right presidential candidate Evelyn Matthei has vowed to review the public-private contract. Economist Jorge Quiroz, representing Chile’s Errázuriz Group that has mining rights in the salt flats, asserted that Chile stands to forego $5 billion by sealing a direct agreement instead of holding a competitive tender. Quiroz is now advising Chile’s hard-right presidential hopeful José Antonio Kast. On the left, Communist rival Jeannette Jara has also panned Codelco’s venture with SQM. While all the presidential contenders have suggested they would respect the contract, the next administration could seek to add strings that could complicate its execution.

For his part, Codelco Chairman Máximo Pacheco has pushed back on the criticism, saying the deal was Chile’s “most transparent” ever and that a tender for SQM’s stake, rather than direct negotiations, would have implied a costly supply interruption. Corfo has echoed his arguments.

SQM declined to comment for this article, but on the recent earnings call, management described the heated debate over the joint venture with Codelco as election season “noise.”

Meanwhile, analysts privately told AQ that a tender could award Chile’s prized lithium reserves to a Chinese state enterprise, risking backlash from the U.S., Chile’s top source of foreign investment. Unlike other OECD countries, Chile has no mechanism to block such a result on grounds of national interest.

Beijing remains ever-present; Chengdu-based Tianqi is SQM’s second-largest shareholder, with a 22% stake. Tianqi has sought, thus far unsuccessfully, to thwart the SQM-Codelco contract with demands for a shareholder vote. Regulators in Chile and countries where SQM has distribution channels, namely Brazil, Japan, Saudi Arabia and South Korea, as well as the EU, have blessed the deal. But China, where SQM processes lithium sulfate, seems to be dragging its feet. The country is Chile’s top trading partner and the destination for most of the world’s lithium. It’s not clear what would happen if Beijing put up a roadblock.

Skeptical stakeholders

Back at home, SQM has set ambitious environmental targets. By 2040, the company has pledged to achieve carbon neutrality and reduce its water consumption and brine extraction in Chile by 65% apiece. Under its Salar Futuro project, the company plans to apply for an environmental permit next year to use new water-saving technologies, including a form of direct lithium extraction (DLE), to transition away from its current evaporation method.

Critics are unconvinced. Regardless of technology, lithium mining sacrifices the fragile ecosystem around salt flats for EVs that few Chileans can afford to buy, prominent environmentalist Cristina Dorador told AQ. Dorador highlighted damage to vital microorganisms that sustain a broad range of biodiversity, including threatened flamingos.

The many Indigenous communities who live near the salt flat must also be consulted for the SQM-Codelco deal to go through. Some support lithium mining, while others are wary. Early on, one group accused SQM and Codelco of forging a deal “behind their backs.” Indigenous critics such as Ercilia Araya cite Codelco’s spotty social and environmental track record. “Clearly this lithium has to be taken advantage of, but in a reasonable way,” Indigenous legal adviser Ariel León Bacián said at a recent congressional hearing. “Codelco is not up to the task, and neither is the government.”

The hearing was conducted by a congressional commission tasked with investigating the new partnership. In May, the commission voted overwhelmingly to recommend the deal be scrapped. Although it’s not binding, the lopsided outcome reflects skepticism that might prove hard to shrug off.

For SQM and other lithium miners, battery innovations, the pace of energy transition, and global recession pose additional risks. And with China dominating the resource, there is no certainty of a lithium price rebound at a time when market forces have taken a back seat to power politics on the international stage. For now, SQM will carry on in Chile, with or without its state partner, at least through 2030. From there, this tale of shared fate could take another dramatic turn.