December marked two momentous anniversaries in U.S.-Panamanian relations: the 35th anniversary of the invasion that overthrew dictator Manuel Noriega in 1989 and the 25th anniversary of the handover of the Panama Canal in 1999. But President Donald Trump has recently suggested that he wants to take the Canal back, by force if necessary.

Leave aside the immorality of invading a close U.S. ally and stable democracy in the Western Hemisphere. Would the U.S. benefit from reclaiming the Panama Canal, which it constructed and operated until December 1999? The short answer is “No.” The U.S. gave up the canal for geopolitical reasons as a way to address important security threats. The threats were addressed, and the U.S. has reaped substantial rewards since. Trying to take it back now would do it more harm than good.

The Panama Canal is absolutely central to Panamanian national identity. If the U.S. were to launch an unprovoked invasion, it would badly damage its reputation in the region and strengthen China’s growing influence. While Latin Americans view China’s presence with mixed feelings, aggressive U.S. actions would drive Panama closer to the Asian country, undermining the stated goal of Trump and some of his cabinet members, including the new Secretary of State, Marco Rubio. Instead of military threats, the U.S. should focus on supporting Panama’s stability and maintaining good relations with this close ally.

Reasons for the canal handover

It’s important to remember that the U.S. agreed to give up the Panama Canal to avert three major security threats in Latin America, an effort that has been successful up to the present day.

A top concern was the spread of anti-imperialist sentiment. The end of the Second World War triggered a global wave of decolonization. But a treaty from 1903 had declared that the U.S. would control the canal and surrounding strip of land as “if it were the sovereign of the territory.” With tens of thousands of U.S. settlers called “Zonians,” the Canal Zone was a mini-U.S. colony.

Anti-colonial sentiment grew. Panamanians resented having their country cut in half by a foreign power and received barely any benefits from the canal. In 1964, Panamanian students entered the Canal Zone and flew the Panamanian flag in protest. The ensuing violence killed at least 20 Panamanian protesters and four U.S. soldiers. This became known in Panama as “Día de los Mártires” (Martyrs’ Day), and led to a diplomatic crisis and more sympathy for the students’ nationalist cause.

The second threat was the spread of guerrilla violence in Latin America in the 1960s and 1970s. The Cuban Revolution of 1959 inspired similar movements in other countries, including in neighboring Colombia (from which Panama seceded in 1903) and nearby Nicaragua. These movements were leftist—but also nationalist—framing their struggles as national liberation from U.S. domination. The Soviet Union made use of the narrative, blasting the U.S. for its “colonizing policy” in Panama.

The final threat came from a left-wing and nationalist military dictatorship that seized power Panama in 1968. Its leader, General Omar Torrijos, had close relations with the country’s Communist Party, enacting land reform, and flirting with Communist Cuba. But his biggest cause was the Panama Canal. Torrijos was willing to go to extreme ends to wrest control of the canal. Plans were apparently drawn up to use explosives to blow up parts of the canal if the U.S. refused to cede control and to launch a long-term guerrilla struggle within the Canal Zone.

The U.S. became keenly aware of these threats in the early 1970s, and the Richard Nixon administration began to negotiate a possible transfer. Henry Kissinger, the Secretary of State, explained: “If these [Canal] negotiations fail, we will be beaten to death in every international forum and there will be riots all over Latin America.”

The negotiations were completed under President Jimmy Carter, with the Torrijos-Carter Treaties signed in 1977. Carter convinced some Republicans and most Democratic senators to accept the transfer.

By putting an end to the Canal Zone and promising the handover of the canal itself in 1999, the two treaties removed a major source of anti-U.S. grievance. While Carter was partially motivated by moral conviction, there was also a cold geopolitical logic at work. The treaties shielded the U.S. from Soviet and Latin American charges of imperialism and ensured the long-term operation and neutrality of the Panama Canal.

The treaties also set the stage for close ties between the U.S. and Panama. This did not happen immediately. After Torrijos died in 1981, his successor, Manuel Noriega, turned more vicious as a ruler and more hostile toward the U.S., prompting a full-scale U.S. invasion in December 1989. Surveys suggested that Panamanians strongly supported the invasion—because it was designed to protect democracy, not to retake the canal. And Panama became a democracy—and remained one, now with the same Freedom House score as the U.S. itself.

Panama and the U.S. today

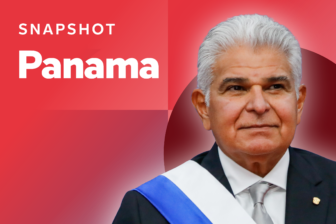

Today, Panama is a staunch U.S. ally. Its conservative president, José Raúl Mulino, won office in 2024, promising to end illegal migration through the Darien Gap. Even when the ostensibly left-wing Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD) is in power, Panama tends to support U.S. policies, such as refusing to recognize Nicolás Maduro as Venezuela’s president.

Panama is also notable for producing virtually no migrants, partially because of its booming economy. Over the past three decades, Panama has enjoyed one of the fastest economic growth rates in Latin America and today has the highest GDP per capita (PPP) in the region. It is no wonder that Panamanians do not want to leave. Much of its new prosperity has to do with how well Panama manages the canal.

Panama has operated the canal with consummate professionalism. In the 1990s, the country amended its constitution to guarantee the independence of the Panama Canal Authority (ACP). Unlike other state-owned enterprises in Latin America, the ACP is run by technocrats who manage the canal better than the U.S. did. Transit times and accident rates dropped sharply after the 1999 turnover, and Panama massively expanded the canal in 2016 at great expense. As the biggest canal user, the U.S. has benefited from these improvements. And it has enjoyed these benefits without paying for a colonial apparatus.

What about the claims that Panama has charged U.S. ships excessive rates? It is true that in some years, the ACP has raised transit fees. But the canal depends on a complicated system of locks—and thus an ample water supply. In 2023, Panama suffered its worst drought in decades, requiring the canal authorities to restrict the number of transits through the canal. Ships could skip the queue, but they would have to pay more for this privilege. Canal fees are applied transparently and neutrally to all countries.

Why retaking the canal would be a disaster

If Panama is a textbook case of decolonization done right, recolonization would be a catastrophe. The canal is not real estate for Panama. It is at the very heart of its sense of itself as a nation. An unprovoked invasion would trigger a powerful backlash and turn the U.S. into a regional pariah.

It would also play into the hands of the Chinese. While it is true that China has become an increasingly important actor in the region, according to surveys, Latin Americans have mixed feelings about the Asian nation. If the U.S. were to retake the Panama Canal, it would provide China precisely the rhetorical ammunition needed to present itself as a responsible alternative to an out-of-control U.S. It would likely make Panama more pro-China, not less.

If the U.S. wants to counter China and reduce migration to its territory, it should help Panama to remain the success story that it is—not retake the canal. Trump’s threats have already prompted an indignant response from Panama. It is in U.S. self-interest to stop this self-destructive saber-rattling now.

Subscribe to The Americas Quarterly Podcast on Apple, Spotify, and other platforms