SOLVING LATIN AMERICA’S FOOD PARADOX

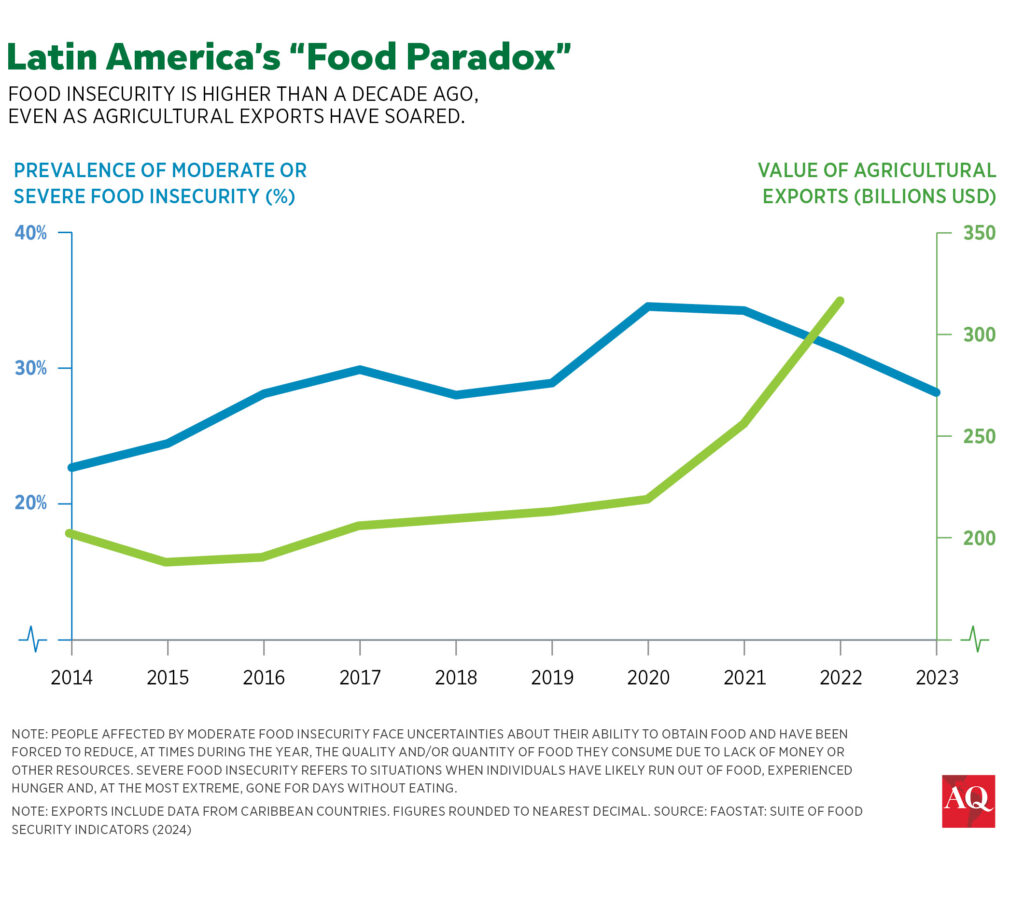

The region’s agriculture exports are booming, but food insecurity is higher than a decade ago. What can be done?

BY JOHN OTIS | OCTOBER 16, 2024

PHOTOGRAPHY BY LUCÍA MERLE

This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on food security in Latin America | Leer en español | Ler em português

TIGRE, Argentina — Lorena Hernández backs up her Ford to a food warehouse, and fills the SUV with so many bags of dried mashed potatoes, bottles of fruit juice and boxes of frozen broccoli that there’s barely room left for her to fit behind the wheel.

Hernández is taking the fare, provided by the nonprofit Argentina Food Banks, to a community center in Tigre, just north of Buenos Aires. Although tourists flock to Tigre for its craft shops, riverside restaurants and boat excursions, the community center sits in a hard-bitten area of one-story brick huts whose residents are often unemployed—and hungry.

At the community center, built in a former coal-packing plant, boys and girls wolf down bowls of beef stew and bread as Hernández looks on. During her 17 years coming here, she has devised ways to gauge how well Argentina is doing. When things are looking up, demand for meals falls off and the kids shy away from foods they don’t care for, like lentils.

But these days, the place is always packed. And the kids are no longer picky.

“Now,” Hernández said, “they devour everything.”

Similar scenes are playing out across much of Latin America today. Call it the food paradox: Even as the region produces and exports more food than ever before, it faces enormous challenges feeding its own people.

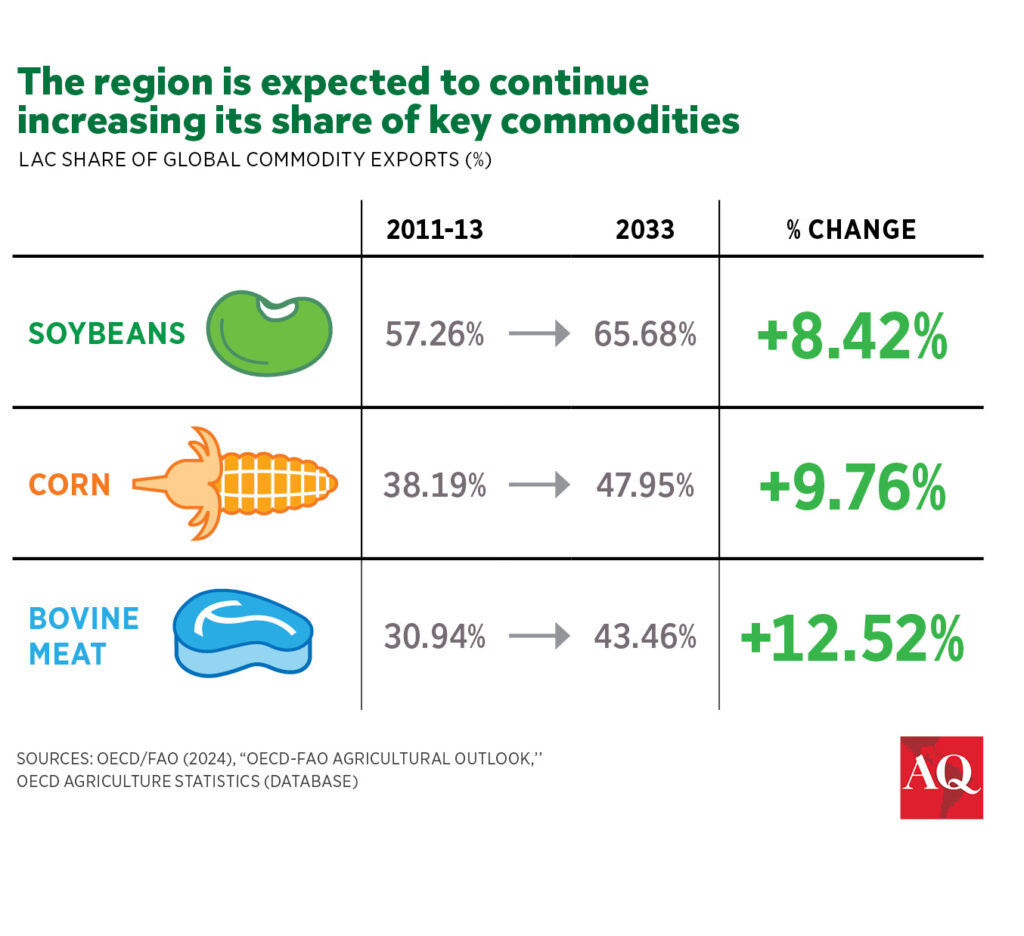

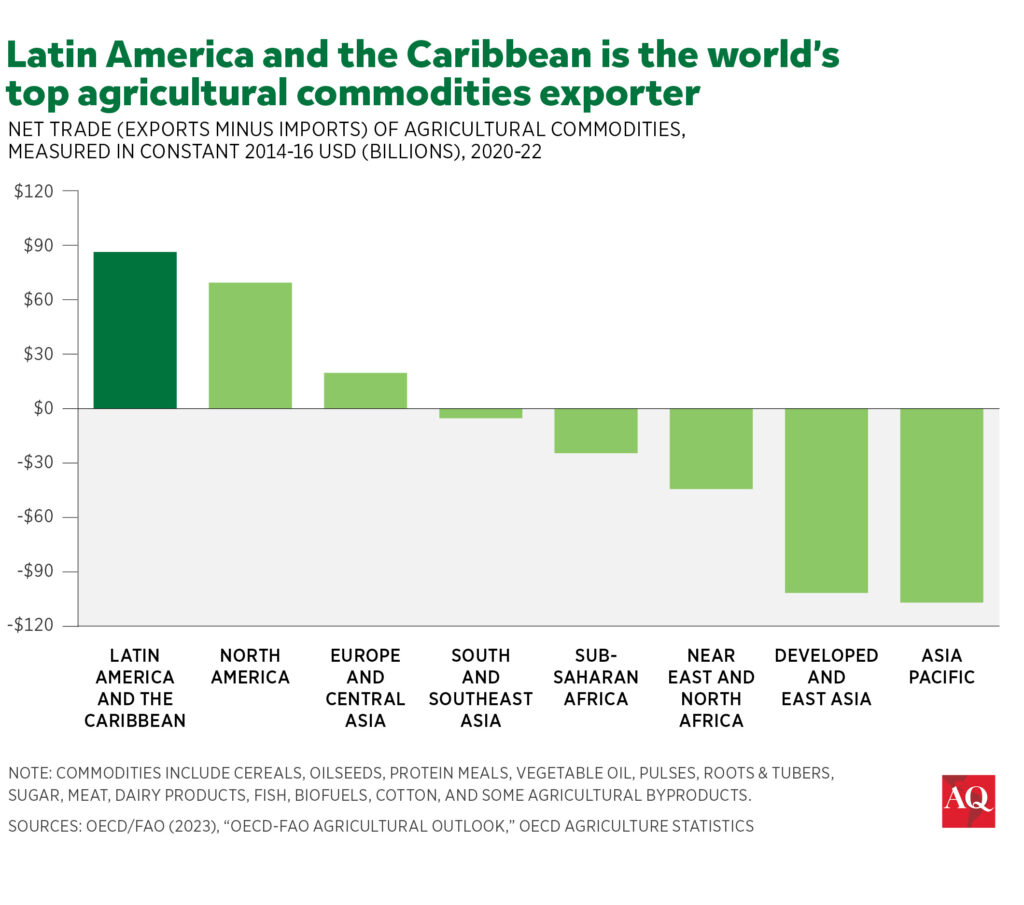

Latin America has in many ways become the world’s breadbasket. Over the past two decades, the value of its agricultural exports rose a whopping 500% to $316 billion in 2022, the last full year data was available. No other region has a larger farming surplus. It is the source of more than 60% of the world’s soybean trade, almost half its corn, and more than a quarter of its beef. Three out of four avocados come from Latin America, as does much of the world’s coffee.

At the same time, about 28% of people in Latin America and the Caribbean suffer today from moderate or severe food insecurity, meaning they lack regular access to enough safe and nutritious food for normal health and development. That number is down from its peak during the COVID-19 pandemic, but still six percentage points higher than in 2014, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). That means an additional 48 million people are suffering from food insecurity compared to a decade ago.

The food paradox infuriates people like Martín Caparrós, the Argentine writer and author of Hunger, an award-winning book that examines why so many people go hungry in a world of abundance. He has called Argentina “an extreme case of an extremely shameful situation.”

But the phenomenon is region-wide, intimately linked to recent economic ups and downs. Latin America saw strong progress in reducing poverty and hunger during the prosperous 2000s, but several of the biggest economies including Argentina and Brazil endured severe recessions starting in the mid-2010s, while Venezuela teetered on collapse. Then came COVID, which hit Latin America especially hard. The ensuing spikes in unemployment, inflation and hunger are still being felt.

“We lost 15 years with COVID,” Máximo Torero, a Peruvian who is chief economist of the FAO, told AQ. “The levels of hunger we have today are the same as 15 years ago.”

Latin America has in many ways become the world’s breadbasket. At the same time, about 28% of people in the region today suffer from moderate or severe food insecurity.

The good news is that much of Latin America is gradually getting back on the right track. From Mexico to Colombia to Brazil, presidents have declared fighting hunger a top priority. Government agencies, not-for-profit groups and private foundations are coming up with often novel ways to get a wider variety of nutritious food to more people. The goal is to create a better breadbasket, a Latin America capable of nourishing the world while at the same time providing food security to its own people.

A FOOD RESCUE MISSION

Much of the work goes well beyond just distributing food to the neediest.

On a recent morning in La Plata, a provincial capital 35 miles southeast of Buenos Aires, Sebastián Laguto was tooling around in a pickup visiting farmers on the edge of the city. His truck was emblazoned with green letters spelling out his mission statement: “Rescuing fruit and vegetables.”

Laguto, a volunteer for an area food bank, works with farmers to salvage oranges, spinach and other produce that is misshapen, slightly bruised or a tad overripe. Such products are often rejected by food companies and supermarkets even though they are perfectly edible. Argentina’s government estimates an astounding half of all the country’s fruits and vegetables are eventually thrown into compost heaps or landfills—a loss rate similar to many other countries.

“Wasted food could solve the problem of hunger,” Laguto told AQ. “The truth is there is enough for everyone.”

One frequent donor to La Plata’s food bank is Nicolás Marinelli, an area farmer. He loves working the rich, black soil—he proudly shows off the tractor tattoo on his right bicep—but the unpredictability of farming has taken its toll. A stretch of hot weather suddenly overripened 4,000 pounds of broccoli, leading buyers to take just 250 pounds. More recently, a cold wind tore the green and white leaves of his chard, rendering them unpresentable for supermarkets.

“They haven’t lost any of their nutrients,” he said with a shrug, noting that at least the food bank will accept his imperfect produce.

Argentina certainly can’t afford to waste any more food. Over the past year inflation spiked above 200%, leaving many people struggling to get to the end of the month. Since President Javier Milei took office in December, his government has devalued the peso, slashed the government workforce, and cut subsidies for electricity and public transportation. This has brought down inflation, but contributed to a rise in poverty, at least for now. UNICEF says some 1.5 million Argentine children are now missing at least one meal per day.

Argentina Food Banks, which includes the food bank in La Plata, was founded in 2001 during the country’s worst-ever economic crisis. The network now has 20 food banks nationally, which distribute leftover produce and groceries donated by farmers, food companies and supermarkets, to some 4,500 community groups. The funding comes from several sources, including the Citi Foundation.

Argentina’s government estimates that half of all the country’s fruits and vegetables are eventually thrown into compost heaps or landfills—a loss rate similar to many other countries.

“As an Argentine, it pains me to see so much poverty,” said Mario Bañiles, director of the organization’s location in Tandil, a city 220 miles south of Buenos Aires. “The good thing is that there are a lot of people willing to help take care of their neighbors.”

One of the beneficiaries is Daniela Sussani, a 19-year-old single mother who lives on the outskirts of Buenos Aires. Her 16-month-old son, Bruno, has a ravenous appetite, gulping down eggs, noodles and rice whenever they’re available.

But Sussani is unemployed and the shelves of the apartment she shares with her mother are sometimes bare. So rather than feeding Bruno the solid food he needs, she’ll sometimes try to nurse him to sleep. It doesn’t work very well.

“If he eats, he sleeps through the night. But if not, he wakes up all the time,” Sussani said. “I’m worried about him.”

DAUNTING OBSTACLES

These recent struggles mean Latin America will likely fall short of the UN’s sustainable development goals of ending hunger and achieving food security by 2030.

One problem is the price tag. The FAO says the cost of a healthy diet in Latin America and the Caribbean today is, on average, higher than in any other region in the world. (This is partly a product of the exceptionally high cost of food imports in Caribbean nations.) The organization’s representative for the region, Mario Lubetkin, lamented, “We are moving further and further away from meeting the 2030 agenda.”

José Graziano, a former director general of the FAO who helped design Brazil’s much-lauded “Zero Hunger” program in the early 2000s, said the region’s drive to export farm commodities can drive up prices for those same staples at home. Brazil, for example, is one of the world’s largest rice exporters. But Graziano said the country often fails to keep enough on hand for local consumption and ends up importing the grain, leading to higher prices for Brazilians.

“It’s a perverse system,” Graziano told AQ.

Because many people resort to cheap, processed foods that have extended shelf lives and can survive long hauls to remote jungle and mountain villages, the number of overweight and obese people is simultaneously on the rise. “Latin America now has twice as many people suffering from obesity as from hunger,” said Eugenio Díaz-Bonilla, a special advisor to the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture.

Climate change is also a culprit, contributing to crop failures and the spread of funguses, like coffee rust and Fusarium TR4, which attacks bananas. Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine drove up prices for fertilizer, putting it out of reach of many small farmers in Latin America. That meant lower yields and higher supermarket prices.

Yet another factor is the unprecedented number of people all over the region packing their bags and moving. The most dramatic case is Venezuela, where nearly a quarter of the population has fled abroad amid the country’s economic collapse.

“The movement of people leads to the loss of access to food and social protection,” said Susana Raffalli, a food security and nutrition expert in Venezuela. “This is happening all over Latin America.”

In the face of such challenges, some governments have been slow to act or too caught up in other crises—from gang violence to natural disasters—to give food security their full attention.

Take Peru. The country is now on its seventh president in the past seven years. That has meant musical chairs at the top of government ministries, making it much harder to carry out coherent social protection programs. Now, 51% of Peru’s population is food insecure. A decade ago, that rate was about 38%.

Carolina Trivelli, who was Peru’s Social Development and Inclusion Minister from 2011-13, told AQ, “If you ask: ‘Who is responsible for food security in Peru?’ the answer is: nobody.”

Several government food distribution programs have been marred by theft, bribery, and organized crime. The most infamous case involved Alex Saab, a Colombian businessman who supplied food for a Venezuela handout program known as CLAP. In 2019, the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned Saab, claiming he used overvalued CLAP contracts to “loot hundreds of millions of dollars from starving Venezuelans.” What’s more, it was poor quality food. A chemical analysis of CLAP powdered milk showed that to get their daily calcium, children would have had to guzzle up to 41 glasses of the stuff.

Prosecutors in Mexico have charged about 90 people at Segalmex, the government food security agency, in a probe over the alleged embezzlement of more than half a billion dollars. In Colombia, President Gustavo Petro announced in his 2022 inaugural address that combatting hunger would be his first priority. But his government has been weakened by a widening embezzlement scandal surrounding its purchase of overpriced tanker trucks to provide drinking water to poor Indigenous villages.

“Petro talks all the time about hunger,” said Felipe Roa-Clavijo, a food security expert at the University of the Andes in Bogotá. “But he hasn’t done very much.”

In Argentina, Milei temporarily halted the distribution of government food to soup kitchens to investigate alleged corruption by the previous government. A new scandal erupted in May when 5,000 kilos of milk, corn flour, beans and other staples nearing their expiration dates were discovered sitting in government warehouses in Buenos Aires and Tucumán.

“We are using the same tools today that we used 10 years ago. But poverty and hunger are different.” —Carolina Trivelli, Peruvian social development and inclusion minister, 2011-13

TURNING THE NUTRITIONAL TABLES

Experts say that Latin American governments need to prioritize food security and boost spending on programs that have a track record of success, like school-feeding campaigns. They also need to reorganize existing programs—such as money and food handouts—and use tools like tax policy and nutrition regulations to promote healthier eating.

“You need an overall strategy and then you need to finance it,” said Díaz-Bonilla of the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture. “Otherwise, it’s just a wish list.”

Many countries have embraced conditional cash transfers. These programs encourage parents to invest in their children by keeping them in school and getting them medical check-ups and vaccinations. In exchange, they receive monthly stipends allowing them to buy, among other things, more food. Latin America pioneered cash transfer programs, with the first launched in Mexico in 1997.

But they require a reset.

“We are using the same tools today that we used 10 years ago,” said Trivelli, the former Peruvian minister. “But poverty and hunger are different.”

For example, poor rural residents continue migrating to Latin American cities. But these newcomers tend to move frequently and bounce between informal jobs, making it more difficult to register for cash transfers and other benefits.

Housing, bus fare, easy access to alcohol, and extortion by criminal gangs make cities more expensive—yet stipends are often still indexed to the cost of living in the countryside. “It’s a lot harder to address urban poverty than rural poverty,” said Graziano, the former FAO director general.

Tweaks to the system are also required because handouts don’t always end up in the pockets of the neediest. UN research published last year found that slightly more than half of all cash-transfer recipients in Latin America lived above the poverty line.

That was the case in Mexico, where the Andrés Manuel López Obrador government scrapped longstanding welfare programs in favor of new ones to help senior citizens, unemployed youths, farmers and people with disabilities. But Mexico’s poorest ended up receiving a smaller proportion of social spending, according to government data compiled by the Associated Press. Extreme poverty edged up.

Government handouts can also blind public officials to the bigger picture. With elections looming, cash transfers can generate votes. But they should not supplant projects that can have more impact, said Ignacio Gavilan, senior director of food systems partnerships for The Global Food Banking Network who spent years working in Central and South America.

“In the Petén rainforest in Guatemala, everyone is drinking Pepsi because the water is undrinkable,” he said. “The government would rather give out subsidies than build water systems.”

To promote healthier diets and get more cash into the hands of small farmers, government agencies in Colombia have a mandate to directly purchase fresh food from local producers. That cuts out intermediaries who can get these goods to faraway markets but who pay famers lower prices. Colombia’s congress has also approved tax breaks for companies that donate to food banks.

Torero, the FAO chief economist, said progress requires better coordination. He points to huge sums wasted on overlapping projects by multilateral agencies, with many unwittingly “funding the same thing in the same country.”

Fish farming is a relatively cheap and efficient way to produce protein. But Torero said countries must also improve cold-chain storage and transportation so fish and other perishables can reach more people in remote areas.

To avoid duplication, governments could mesh disaster relief with regular food programs. In most countries responsibility for nutrition and food security is spread among agriculture, health and social protection ministries, which often leads to confusion and inertia.

“Governments could name a food czar to coordinate everything,” Trivelli said.

There are also lessons to be learned from Brazil, which made headlines in the early 2000s for its successful efforts to reduce poverty and hunger under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

Brazil relied on a combination of robust cash transfers, school-feeding, and other programs, while putting together a comprehensive database of at-risk families. This single national registry allowed government agencies to quickly scale up assistance during the COVID-19 pandemic and other emergencies, said Mary Arends-Kuenning, an economic demographer at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign who has carried out extensive research in Brazil.

“Hunger is not natural. It is, above all, the result of political choices.” —Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva

When Lula returned to the presidency for a third term last year, he picked up where he left off. He reestablished Brazil’s National Council for Food and Nutritional Security, banned ultra-processed foods from the school-feeding program and boosted spending for that program by 35%.

As it turns out, funneling more money into the fight against hunger makes good economic sense. Research by the UN’s Economic Commission on Latin America and the Caribbean and World Food Program found that it would cost countries 1.5% of their annual GDP to provide needy people with healthy food. By contrast, the cost of doing nothing—in terms of health care and lost productivity—would be 6.4% of GDP.

Lula endorsed this approach at a July summit in Rio de Janeiro at which he proposed forming a global alliance against hunger.

“Hunger is not natural,” he said in a speech. “It is, above all, the result of political choices.”

RELYING ON FOOD BANKS

“This country produces so much, but everything is so expensive.” —Yanet Lozano

Yanet Lozano is not sure who to blame. A single mother of three young children, she earns $400 a month cleaning houses in the tonier neighborhoods of Tigre, but said inflation makes it nearly impossible to keep her family fed. Pinning laundry to her front-yard clothesline on her day off, Lozano, who is 31, said, “This country produces so much, but everything is so expensive.”

Her mood brightens when talk turns to the community center, the one run by Lorena Hernández that’s conveniently located a few blocks away. In its kitchen, cooks turn potatoes, pasta, carrots and other groceries supplied by Argentina Food Banks into simple but nutritious fare.

Lozano sometimes sends her kids to bed on just tea and bread, but at the center, at least they get a solid lunch. She added, “I don’t know what we would do without it.”

Merle is a photojournalist based in Buenos Aires. Her work has been published by Getty Images, Financial Times and the AP as well as several news organizations in Argentina.