This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on the 2024 U.S. presidential election and its impact on Latin America

On Saturday morning, March 9, 1940, the Mexican Army’s marching band was playing joyful songs. Cameramen and journalists gathered in the courtyard of 33 Calle Sevilla in Mexico City, trying to get a good photograph of the protagonists of the day: the doctors opening the first state-run morphine dispensary for drug addicts in Mexico City.

That dispensary, the first of many planned for the entire country, was the spearhead of a broad national program that foresaw the creation of a state monopoly to supply morphine, at nominal prices and as prescribed by doctors, to Mexicans suffering from drug addiction.

The objective was to alleviate addicts’ demand for morphine. As the government-employed doctors explained that morning, the dispensaries would reduce their dosage, bit by bit, taking them through a process of gradual detoxification. Those who signed up for the program would be allowed to continue their normal lives if the doctor assigned to them thought they would not represent a danger to society. And even for incurable cases of addiction, the dispensaries would at least allow them to stop depending on the illegal drug market. That, it was thought, would help weaken the drug trafficking networks already beginning, at that moment, to proliferate in the country. By offering a safe place to inject morphine, the dispensary promised to reduce the spread of sexually transmitted infection and combat the tendency among some addicts to resort to criminality to fund their drug consumption.

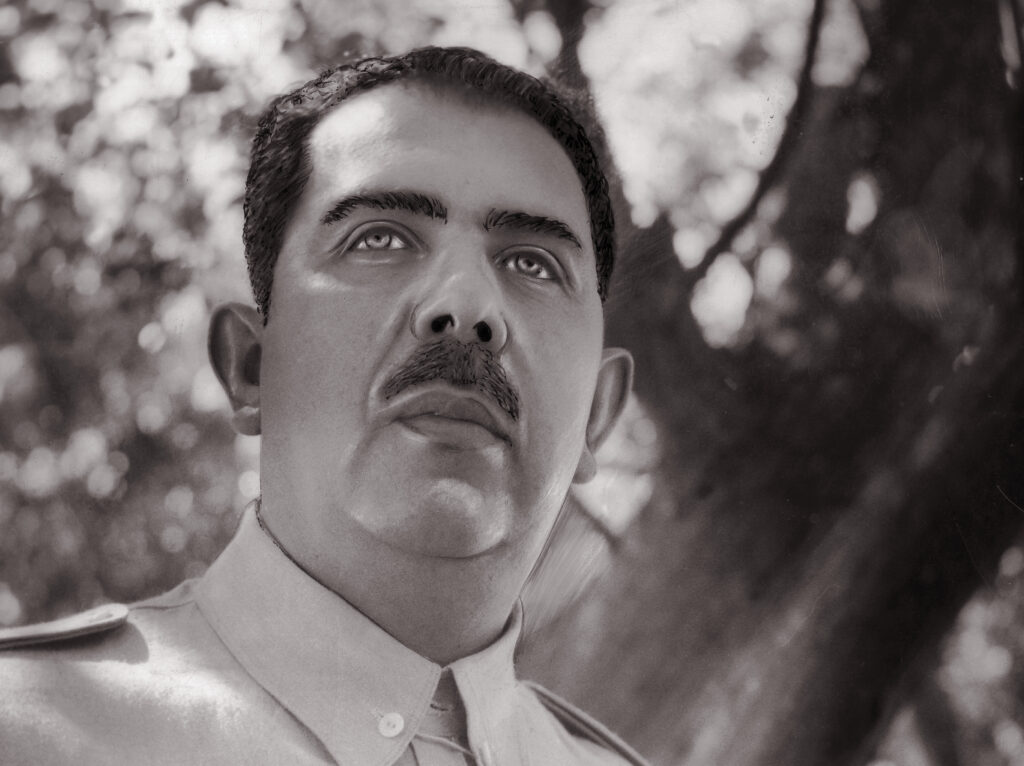

This program, adhering to an approach that today would be called addiction “maintenance,” was new in Mexico—and in large part its implementation was due to the efforts of physician Leopoldo Salazar Viniegra, who had headed a government directorate on drug addiction in the late 1930s. Although unprecedented and highly original in the Mexican context, the program was very similar to others proposed by progressive physicians in other countries. Beginning in the late 1910s, dozens of clinics and dispensaries had been established in several U.S. cities to provide morphine to drug addicts at low prices, as well as addiction treatment programs that were radical for their time.

The program was made possible by an important reform to federal drug laws, which had previously required all drug addicts to be confined to hospitals, that Salazar Viniegra had managed to secure just a few weeks before the opening of the dispensary on that cold morning of March 9. It looked like the beginning of a new paradigm for drug policy in Mexico.

U.S. pressure against the drug reform

But the high hopes quickly faded. The dispensary on Calle Sevilla operated for only a couple of months. On July 3, the federal government officially suspended “for an indefinite period of time” the reform to the drug law that had been approved earlier that year. Although the motivation was never formally clarified, the suspension was a direct consequence of pressure from the U.S. government.

That pressure began as early as April 1938, when longtime U.S. anti-drug official Harry J. Anslinger, then at the helm of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, first caught wind of Salazar Viniegra’s project. Anslinger’s response—and its consequences—can be reconstructed from his correspondence with officials in the U.S. and Mexico, preserved in the U.S. National Archives.

From that point on, Anslinger sought to put a stop to the Mexican plans, which differed from the prohibitionist logic the U.S. government had been promoting at the international level since the beginning of the century, particularly since the Shanghai Convention of 1909, which set in motion the global regime of drug prohibition that has persisted to the present day.

Between spring 1938 and early 1940, U.S. diplomats put strong pressure on the government of President Lázaro Cárdenas to replace Salazar Viniegra as health secretary. The doctor was seen as a danger. Besides his efforts to move toward an “addiction maintenance” policy, the U.S. was scandalized by his other views. Salazar Viniegra argued that marijuana was not harmful to health—a view he had derived based on his own experiences sampling the herb, which he talked about at several conferences and in public writings. Some doctors even accused him of offering marijuana cigarettes to his patients and smoking them during work meetings. But Salazar Viniegra failed to grasp the gravity of the situation. He saw marijuana as a less harmful substance than tobacco.

Salazar Viniegra’s positions were intolerable to conservative groups in Mexico and to U.S. diplomats. Anslinger suspected that once the “addiction maintenance” program was in place, the Mexican doctor would seek to move toward a process of marijuana legalization. The U.S. pressure was on. Salazar Viniegra had to be stopped.

The threat of a medical embargo

The U.S. government had several methods available to put pressure on Mexico. But the main one was threatening an embargo on Mexico until its new drug regulations were repealed. In this regard, Anslinger had an ace up his sleeve: the U.S. Narcotic Drug Import and Export Act of 1922. That act prohibited persons or companies subject to U.S. jurisdiction from exporting narcotic drugs, primarily morphine and codeine, to countries that, in the narcotics commissioner’s judgment, did not maintain an adequate system of control under the 1912 International Opium Convention.

In practice, this allowed Anslinger to deny licenses for U.S. shipments of narcotics to Mexico—representing the bulk of Mexico’s supply—as long as he could claim the country could not guarantee they would be used for medical purposes. Panic spread in Mexico. Anslinger’s threat reached the ears of Mexico’s health secretary just hours after the opening of the medical clinic in Colonia Juárez. Alarm bells sounded, and Mexico’s health council held an emergency session on March 12. For a few days, the Mexican government tried to negotiate, but Anslinger’s position was immovable: He would deny any shipment of medicines to Mexico if the reform was not repealed.

The war then engulfing the world worked in Anslinger’s favor. A large percentage of the narcotics shipments coming from Europe and destined for other countries in the Americas now passed through the port of New York. Thus, the supply of chemical precursors needed for Mexico’s nascent pharmaceutical industry lay in Anslinger’s hands. And as if that were not enough, the pharmaceutical industries in Germany, France and Spain had also entered into crisis, leaving Mexico dependent on U.S. production.

Time was on Anslinger’s side—and he knew it. In a confession to a high-level official, he boasted that his plan was foolproof. According to him, the health authorities would begin to back down as they ran out of drugs to “attend to the wounded and sick.”

On July 3, 1940, Mexico’s federal government published the “indefinite” suspension of the Drug Addiction Regulation. Ten days later, the dispensary on Sevilla Street was closed. The band stopped playing.

A century of drug prohibition

The brief history of Mexico’s Drug Addiction Regulation was the beginning and the end of the country’s attempt to build an alternative drug policy to the prohibition-based approach already prevailing in the U.S. Paradoxically, the suspension provoked a radicalization of the drug prohibition-based paradigm in Mexico. Going forward, institutions responsible for controlling drug flows were fearful of Anslinger’s reaction. In the fall of 1942, for example, the Bureau of Narcotics and the State Department threatened again to embargo Mexico if its authorities did not put an end to poppy planting in the Sinaloa highlands. The threat was serious: That same year, Anslinger put a medical embargo on Chile for starting an addiction treatment program similar to the one proposed by Salazar Viniegra a couple of years earlier.

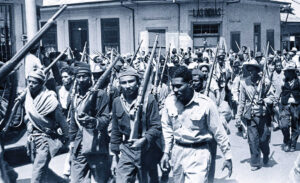

For the rest of the century, Mexico maintained a drug policy that was even more punitive than that of the United States. In 1945, a decree by President Manuel Ávila Camacho made it possible to ship suspected drug traffickers and drug addicts to the forbidding federal prison on the Islas Marías, 60 miles off the coast of Nayarit state, without having them pass through a court of law. In five years, Mexico had gone from a policy of outpatient addiction treatment to outright criminalization of addicts.

Almost 85 years after the army band played at Mexico’s first narcotics dispensary on Calle Sevilla, the country continues to be anchored in a prohibitionist logic. Marijuana use remains unregulated, and the federal government has failed to adopt addiction treatment schemes that have proven successful in other parts of the world. In light of the damage caused by criminal violence in recent years, it seems senseless that alternatives to the prohibitionist model have not been tried.

Recent drug reforms at the state and federal level in the United States offer a new opportunity for Mexico to explore alternatives on how to address the issue of drug use. (The irony here is self-evident.) Will the government of Claudia Sheinbaum, Mexico’s president-elect, take advantage of this opportunity? Time will tell. One thing is certain: In this matter, as in others, Mexico can learn from its own history to imagine its future.

—

Pérez Ricart is an assistant professor of international relations at the Center for Research and Teaching in Economics (CIDE) in Mexico City.