PORT OF SPAIN — When Trinidadian tech support specialist Nikcolai Salandy lost his job with a Miami brokerage firm last July, he shelved his dreams of a career in finance to focus on a different type of investment: a greenhouse to cultivate mushrooms, dragon fruit and microgreens. Salandy is planning to build a 3,000-square-foot facility on family land in the town of Petit Valley outside the capital of Port of Spain, where he grew vegetables as a hobby during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Underpinning the project is a grant of nearly $60,000 from the government of Trinidad and Tobago, which is supporting nascent farmers to help improve the country’s homegrown food supply. The government’s push is part of a Caribbean Community (CARICOM) initiative meant to address rising food insecurity in the region, and growing food import bills draining public coffers.

“The first thing I planted was tomatoes. That wasn’t too successful, but that was the trigger to learn more about farming,” Salandy, 32, told AQ. He attends daily government-sponsored training sessions on shade house production. “I expanded how much land that I used for farming itself, and just delved a little deeper into the whole career.”

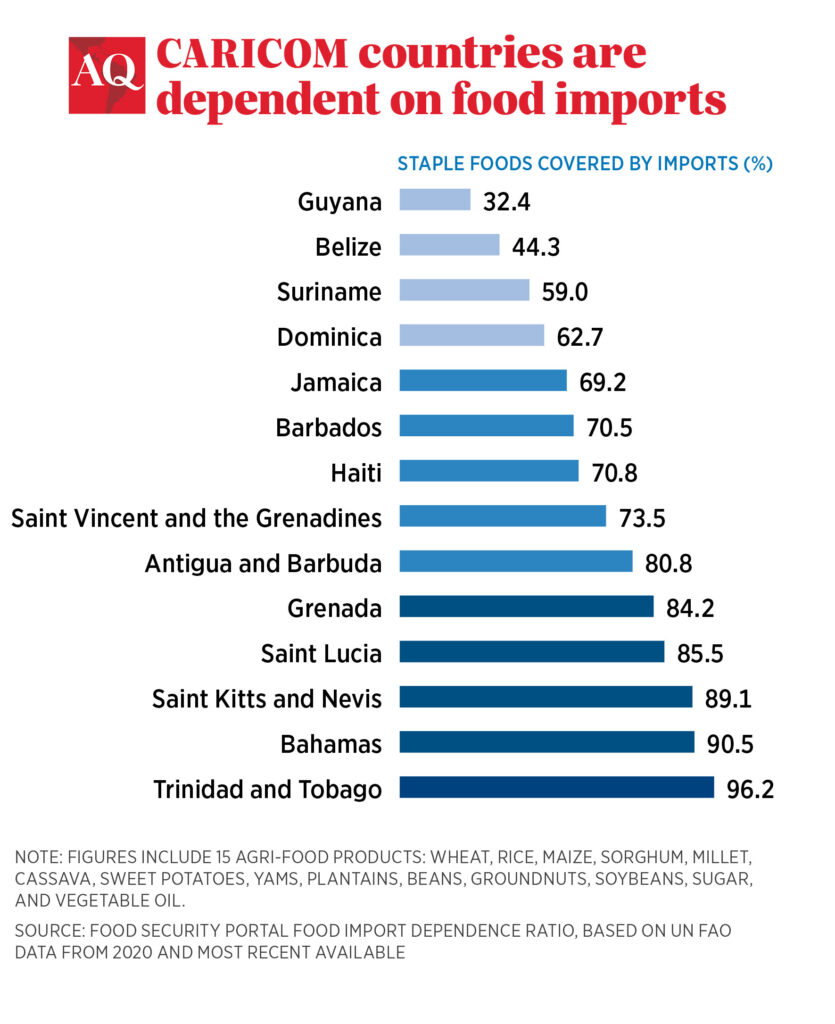

Hunger in the Caribbean region spiked in 2022, with some 4.1 million people—or 57% of the English-speaking Caribbean—reporting food insecurity, according to a study by the World Food Programme and CARICOM. Some countries in the region import more than 80% of the food they consume, creating a regional import bill of $6 billion per year, according to CARICOM. The ambitious plan known as “Twenty-Five by 2025” aims to lower the food import bill by one quarter by 2025, partly by supporting budding agricultural entrepreneurs like Salandy. Food accounts for 20% of the value of total imports in small Caribbean states, compared with 8% for Latin America and the Caribbean as a region, according to World Bank data.

Twenty-Five by 2025 also calls for reducing tariffs on food within the region to encourage intra-regional trade. That shift has been notable in the last several years as Guyana began importing sheep from Barbados instead of New Zealand and Australia. Last year, Belize began exporting soy meal—which it typically sells outside the Caribbean—to Trinidad.

Agriculture as a percentage of GDP in the Caribbean ranges from 13.5% in Guyana to 1.5% in natural-gas rich Trinidad, according to World Bank data, compared with 6.6% in Argentina and 6.8% in Brazil.

Because the Caribbean does not have large amounts of arable land like the United States or Brazil, most of the region’s farming is done at a small scale, like Salandy’s operation, with Caribbean industrial agriculture focused on export crops such as sugar or bananas. The plan seeks to improve small-farm productivity through better infrastructure and more advanced irrigation, while also shifting local eating habits that lean heavily on imported wheat flour toward traditional and locally grown foods such as cassava.

The effort has started to show some results. Jamaica reported record annual food production in both 2021 and 2022, when output topped 800,000 tonnes, according to Agriculture Minister Floyd Green, thanks in part to bigger potato and sweet potato harvests and more raising of goats. Government incentives in Guyana have led to greater cultivation of soy and corn for animal feed, helping cut the cost of local livestock production. Guyanese President Irfaan Ali estimates that meeting the Twenty-Five by 25 target will require $7.5 billion in investment across the region. CARICOM has not yet tallied total investments so far, but the plan will need significant private sector outlays in the coming year, according to Patrick Antoine of CARICOM’s Private Sector Organization.

Jamaican farmer Diandra Rowe, 32, who grows mixed greens as well as herbs such as dill and cilantro that are typically imported, applauds the effort for attracting young agricultural entrepreneurs. “It’s very important that they put a focus on that, because the farming population is aging and if we don’t have more young people coming in, there won’t be continuity,” said Rowe.

Agriculture experts in the Caribbean welcome the initiative as a positive step but believe the target may be too ambitious. “I think they underestimated the size of the task because it’s not only food production,” Dr. Wayne Ganpat, a professor of agriculture who works with organizations in the CARICOM region to boost agricultural capacity, told AQ. He said that critical challenges include high production costs, slow shifts in regional trade regulations and established tastes for imported food. Experts note that Guyana has ample rice production capacity but tends to get better prices outside the Caribbean and thus has little incentive to sell within CARICOM. Dr. Sharon Hutchinson, a food and natural resource economist with the University of the West Indies, says weaning Caribbean taste buds off American fast food is a slow process. “From the smallest child in preschool or primary school, you have to develop taste buds,” she said. “That has to be further reinforced.”