Since construction of a high-end resort began in 2017 on the Caribbean island of Barbuda, part of the twin-island nation of Antigua and Barbuda, residents have been seeking to halt the project. They say the Barbuda Ocean Club and an associated airport undermine local land rights and damage the environment. The country’s government has fully backed the project, calling it economically necessary and environmentally sound. But Barbuda resident and marine biologist John Mussington says part of the island’s shoreline is being sold off to the ultra-wealthy and is leading a case in a powerful court in the United Kingdom to block the airport’s construction.

“You’re going to fence these areas off, create these luxury enclaves that local people do not have access to—what does that do to a local community?” Mussington told AQ. “You’re extinguishing the community for the benefit of these wealthy persons who want to practice their private lifestyle.”

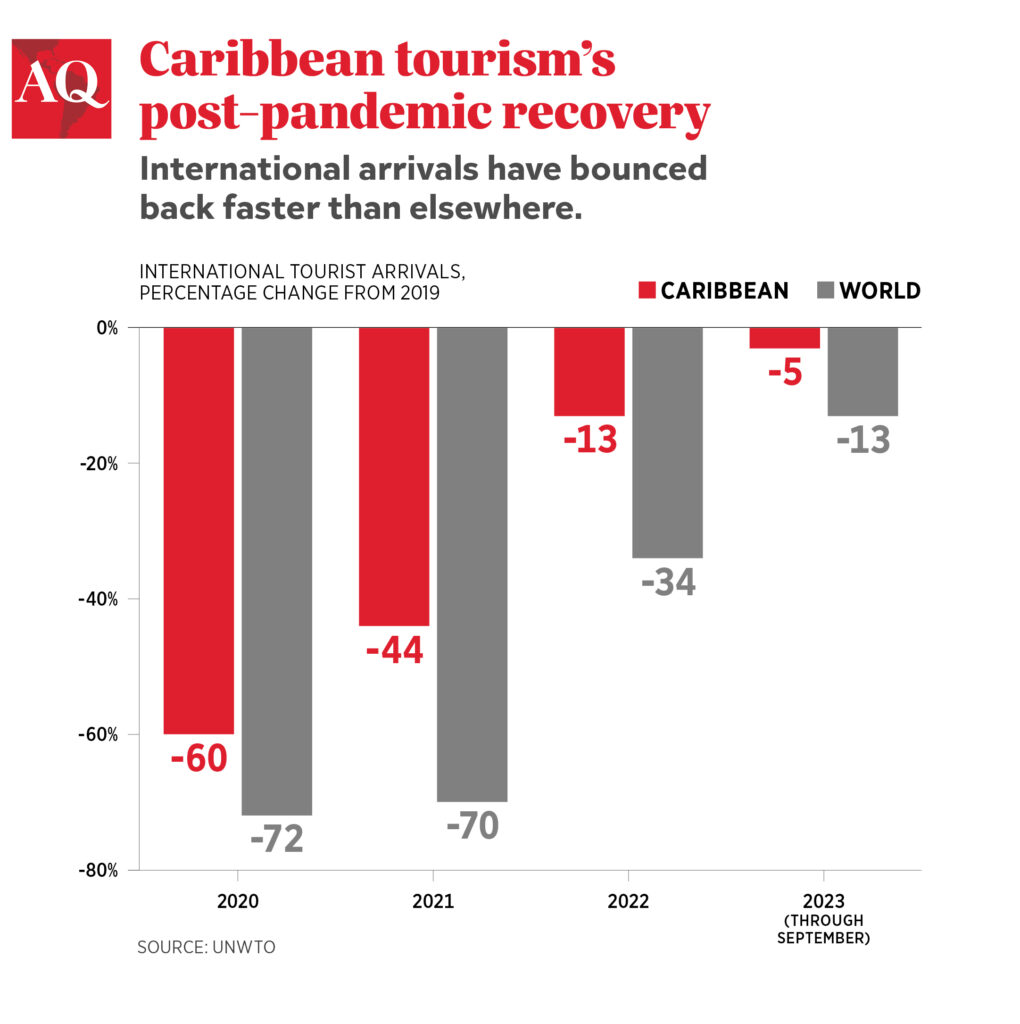

The conflict over the Barbuda Ocean Club is being replicated across the Caribbean, as a rush to build luxury real estate fuels conflicts with residents who say these projects put foreigners ahead of those countries’ citizens. Tourism is a fundamental pillar of Caribbean economies, comprising nearly a third of the region’s GDP on average but reaching as much as 90% in some countries, according to one International Monetary Fund study. Popular all-inclusive resorts have helped bring visitors to the Caribbean for decades but have faced pushback over tourism’s environmental impact, including marine pollution, water usage, and local populations’ access to beaches. More recently, development has trended toward higher-priced hotels and luxury real estate, which has fueled complaints about land rights and rising inequality.

Activists in Saint Lucia have decried the construction of luxury villas by a billionaire family in the area of two iconic peaks known as the Pitons, according to local media. Construction of mansions is booming in the French-speaking island of Saint Barthélemy, better known as Saint Barts. Similar property development has spurred protests by activists in Grenada. Critics say luxury real estate development isolates the world’s ultra-wealthy from local traditions and residents.

But governments of small Caribbean countries say luxury real estate can have less environmental impact than all-inclusive resorts while also providing a critical source of steady revenues for governments facing immense financial pressure. In recent years, hurricanes have become more intense due to climate change, causing greater damage and forcing governments to borrow funds for reconstruction. The region was also one of the world’s most affected by the coronavirus pandemic, as the 2020 grounding of flights and the halt of cruise line activity caused the region’s tourism-dependent economies to contract by 9.8%.

Ronald Sanders, Antigua and Barbuda’s ambassador to the United States, says taxes on high-end real estate were critical along with economic activity by wealthy residents who flew in private jets, helped cushion the financial impact when the pandemic shut down traditional tourism due to flights being halted.

“This, in fact, is the tourism of the future for the Caribbean,” Sanders said. “A Caribbean country can make more money from five luxury properties than from five hotels. In effect, you’re using less space on a small island to earn more money. Surely that makes sense.” The property tax revenue from such projects is necessary to ensure that the country can pay for services such as education and health care, he said, adding that recently approved luxury residences use renewable energy and limited amounts of water.

Pending decision

In November, the London-based Privy Council, which serves as the top court for some Caribbean countries, held a hearing on whether Mussington and another activist have legal standing in seeking to block the airport construction. That decision is expected within the next several weeks. Court rulings so far in Antigua and Barbuda and the Privy Council have allowed the development to move forward.

The Barbuda Beach Club drew sharp controversy in 2017 when residents say Colorado-registered property developer PLH Barbuda LLC, which activists say is owned by U.S. billionaire John Paul DeJoria, began construction on the resort soon after the destruction wrought by Hurricane Irma. Barbuda residents who had been evacuated from the island say construction of the luxury property began before they were even allowed to return, triggering accusations that the project was an example of “disaster capitalism” that takes advantage of natural disasters to advance projects under dispute. A group of U.N. experts in 2022 said the resort’s construction had harmed local wetlands and wildlife and that it was unclear if Barbudans had been fully consulted about it.

A central dispute over luxury tourism in the Caribbean is its impact on residents’ access to beaches for fishing and recreation. Countries, including Jamaica, say regulations require that beaches be available to the public and point to beaches that are maintained by state agencies. But critics say in practice, stretches of coastline can be blocked off by resort security guards or construction crews even if the law does not allow them to. The issue created controversy this year in Jamaica, where Bob Marley’s son Ziggy is leading a campaign to ensure equal access to beaches.

Raymond Pryce, a former Jamaican parliamentarian who follows the issue of coastline development in the Caribbean, says developers have the upper hand because politicians are under tremendous pressure to create jobs. But he adds that betting on luxury resorts has social consequences.

“A wall goes up, a private jet lands, and a famous billionaire is there for two to six weeks out of the year,” said Pryce. “We have these zones of exclusion, and a native population that is underemployed and under resourced—you see the stark differences between the haves and the have nots.”

Ellsworth is a Washington, DC-based journalist with 20 years of experience covering Latin America and the Caribbean.