Eva Copa shook Bolivia’s political landscape in 2021 when she won the mayorship of El Alto, the country’s second-largest city. At just 34, the young Aymara mayor had taken on not only ingrained machismo but also the country’s ruling party and biggest political machine, the Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS), trouncing its candidate by 50 percentage points.

On the campaign trail, she leaned into her identity as an Aymara mother of two from a poor rural household, the seventh of eight siblings, arguing that this background gave her the backbone to help the city chart its own course. This resonated in El Alto, a young, majority-Indigenous, rapidly growing city of 2 million. Near borders with Chile and Peru, it is dominated by a bustling informal economy—and known as a hotbed of confrontational activism. “We have always been rebellious,” Copa told AQ.

Copa’s victory as a former MAS member who split with the party reflects a national shift toward a more diversified political landscape. This shift has diminished the MAS’s hegemony and—to an even greater extent—sapped the influence of the traditional right-wing opposition, said sociologist Fernando Mayorga, who authored an upcoming book about the internal dynamics of the MAS.

Copa was first thrust into the national spotlight in 2019 as Bolivia descended into one of the most profound crises in its history—but she was an unlikely contender on the national stage. Copa had come up in politics through public university councils as she studied social work. She was a leading voice in efforts to make the university system more equitable for women, and in 2015 she was surprised when the MAS named her a junior senator, in part to comply with gender parity laws.

But in November 2019, then-President Evo Morales left the country after a disputed election. Massive street demonstrations and pressure from security forces and the military led him to resign. Right-wing leader Jeanine Áñez took power even as much of the country viewed her as illegitimate. Dozens died in the ensuing unrest.

Wary of increasingly aggressive security forces and of cooperating with Áñez, much of the MAS leadership followed Morales into exile. But Copa stayed. She agreed to become Senate president, even as military leaders threatened to shutter Bolivia’s legislature.

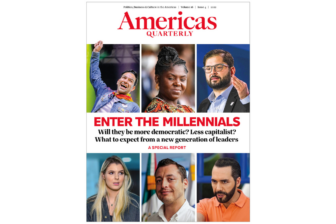

Photo by Gaston Brito/Getty Images.

Copa’s decision to stay and compromise with Áñez lent the new government legitimacy, and many in the MAS viewed this as betrayal in the midst of a coup d’état. However, the decision also helped to keep the National Assembly operating, prevent an institutional collapse, and calm the unrest roiling the country, said Lorgio Orellana, a sociologist at the University of San Simón in Cochabamba who specializes in social and political conflict. “It’s this contradiction that catapults Eva Copa into the national spotlight.”

Due in part to Copa’s leadership, the MAS remained coordinated despite sharp internal divisions, and the legislature repeatedly faced down the new president and the military, checking their power, said Mayorga.

Just one week into Áñez’s government, on November 19, security forces killed eight demonstrators in El Alto. In the wake of these and other killings, “Copa pushed dialogue and agreements, which helped to avoid more military repression,” Mayorga told AQ. Then she helped to lead the successful campaign to call new elections in 2020, which also prevented greater violence.

The gamble on new elections paid off for the MAS, which came back into power alongside current President Luis Arce. “The crisis revealed that women are more loyal and more important than we thought, because most of the legislators who stayed were women,” Copa told AQ. “We demonstrated our political maturity, and we didn’t let decisions that should be made by the Assembly be made by the executive.”

But when the leadership in exile returned, Copa said, they wanted to return to the same old caudillismo, or centralized, personalistic decision-making revolving around Morales and his inner circle. Copa supported Arce’s electoral campaign, but could not remain with the MAS, despite its remarkable track record on poverty reduction and other social indicators since Morales first took office in 2006. Efforts to enforce the old caudillismo are creating instability, Copa said. They are also costing the MAS votes.

El Alto overwhelmingly supported Arce in national elections, but just a year later delivered Copa her victory. This reflects a major political shift: The MAS is being challenged by opposition figures who appeal strongly to elements of the party’s base, Mayorga told AQ.

This favors that base, which will benefit from more diverse electoral options. And while this has weakened the MAS’s dominance, it hurts the traditional right wing more, because the right can no longer attract supporters as the sole influential alternative, Mayorga told AQ. Copa generally supports Arce but has, for example, joined those hammering the administration for its handling of a national census.

As mayor, Copa has focused on attracting investment and formal employment opportunities to El Alto. “We’ve worked first on our economic program and a public-private partnership law to establish social and legal guarantees for investors,” she told AQ.

She aims to attract tourism—capitalizing on Freddy Mamani’s colorful architecture combining Aymara motifs with futuristic modernism—and the cattle industry, for example, with improvements to infrastructure connecting El Alto to neighboring departments and the markets of Peru and Chile. With this focus, Copa “promotes a vision of entrepreneurship, of an ascendant Aymara petty bourgeoisie that seeks to establish a politics of small business development,” said Orellana, “far from the more socialist vision” often associated with the MAS.

As mayor, balancing intense, competing interests has not been easy. “It has forged my character terribly,” she said, as she works mostly with older men, and she faces disrespect often. But, she said, “I’ll tell my kids that their mom was there, and she didn’t let any man or any party push her around.”