Since its return to democracy in 1984, Uruguay has been lauded as a democratic miracle in Latin America, placing ten entries ahead of the United States in The Economist’s 2020 Democracy Index. Now, Uruguayan democracy is once again in the news – but this time, after a 2019 presidential election focused on public security, with a question mark attached.

After a spike in crime rates, with homicides increasing by 46% and reaching a record high in 2018, public security was a major concern in the 2019 presidential elections. A “multicolored coalition” championed by then-candidate Luis Lacalle Pou criticized the Broad Front government’s inaction and campaigned on a “security shock” program to combat the public security crisis.

Upon election, President Lacalle Pou’s coalition claimed a strong mandate to make sweeping reforms, including to the penal code. In July 2020, the legislature passed a 476-article omnibus bill – an “Urgent Consideration Law” or, in its Spanish abbreviation, LUC – with the intent of fulfilling that aim. But the law earned Uruguay a surprising condemnation from three special rapporteurs for the United Nations, while protests have broken out, drawing activists into the streets. Now, the opposition has organized a March 27th referendum that, if approved, may strike down the LUC’s more controversial provisions.

Worries over freedom of expression

Lacalle Pou’s LUC toughens sentencing and limits chances for early release from prison. It includes stronger powers to dismantle protests and imprison anyone who obstructs or “insults” police officers. It declares illegitimate all protests that “impede the free circulation of peoples, goods or services,” regardless of whether they take place in a public or private space.

“In comparison to previous administrations, the LUC significantly empowers the police,” says Diego Luján, a political scientist from Uruguay’s Universidad de la República.

The law also provides for the creation of a Secretariat of State Strategic Intelligence within the executive branch, consolidating various intelligence organizations from the ministries of defense and the interior – and empowering the new organ with the power to request “information as it deems necessary” from government agencies and even private citizens without a formal court order.

Augusto Gregori, former director of intelligence under President José Mujica, compares this new Secretariat to the intelligence gathering of the civic-military dictatorship that lasted from 1973 to 1984. “This isn’t about state intelligence, it’s homeland security,” he says. “And once [this Secretariat] gets started, Pandora’s box opens up.”

Many political scientists, including popular intellectuals like Juan Pablo Cajarville and Pablo Rodriguez Almada, are calling the LUC unconstitutional and a violation of the separation of powers as it shifts towards a more powerful executive branch in Uruguay. For ex-president José Mujica, the rapidly implemented changes of the LUC threaten the “institutional stability” of the country. “It’s a real earthquake,” he said.

On the other hand, Lacalle Pou has repeatedly slammed the opposition by reasserting the mandate he won in 2019 to usher in significant change: “No one can be surprised. …We campaigned talking about (the LUC).”

Yet even the tactics of the reform are disputed. Urgent Consideration Laws have been used several times, but always targeting specific and timely issues, such as the creation of a Social Development Ministry in 2005 and the modification of social taxes in 1992. “The most disruptive element (of the LUC) is in its making almost the entirety of a government program pass through a mechanism that should be exceptional,” said Luján.

High stakes for the governing coalition

The president’s parliamentary majority allowed the bill to pass quickly, but a movement spearheaded by the opposition Broad Front party and the country’s largest trade union (PIT-CNT) gathered the signatures of more than 25% of Uruguayans to trigger an up-or-down referendum. Instead of seeking to strike the entirety of the LUC, however, the referendum only seeks the public’s approval on 135 articles – less than a third of the full law.

Alongside concerns about the quality of Uruguay’s democracy, the fate of Lacalle Pou’s reform package is closely tied to his political future. For Francisco Panizza, a Uruguayan political scientist at the London School of Economics, the government will likely have to succeed in the referendum if they hope to maintain their coalition intact and realize any part of their agenda: “Between the pandemic and the LUC, the government must show that they are capable of doing something, anything.”

The vote is set for March 27, but almost 70% of Uruguayans are still unclear about the actual content of the sprawling law. Journalist Carina Novarese estimates that “most Uruguayans are not interested in (the details of) the LUC because they genuinely don’t understand the LUC itself. The law, the effects – it’s all unclear.”

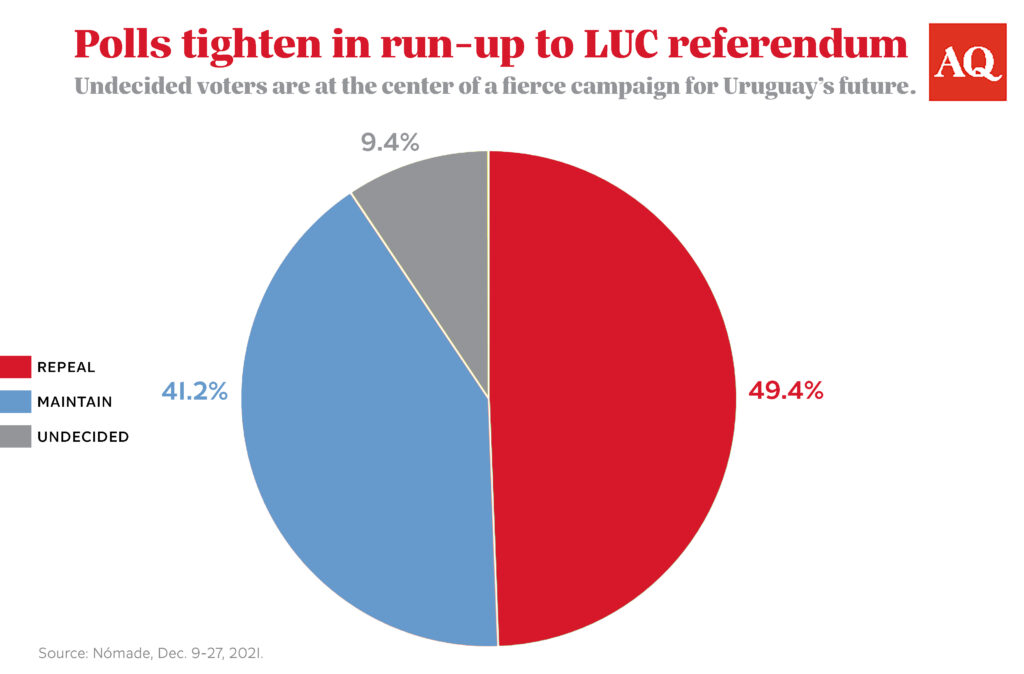

According to the polling firm Nómade, 49% of the population leans towards striking down the disputed provisions, with 41% in favor of keeping them. Undecided voters are at the center of the ongoing campaign, with 9% of the population divided between both camps.

Lacalle Pou’s administration has put all other initiatives on pause until after the vote. “From now until April, everything will be about the referendum” remarked an unnamed senator from the National Party, part of the governing coalition.

Nonetheless, while the LUC poses significant long-term challenges for Uruguay, Novarese says that Uruguay tends to consolidate itself well after referendums, even with contentious issues such as the 1992 referendum on privatization of state enterprises and the 2009 referendum revoking amnesty for dictatorship-era military officers: “In the end, the voice of the people is heard; there isn’t likely to be chaos one way or another.”

—

González Camaño is an editorial assistant at AQ