This article was adapted from AQ’s latest issue on the politics of water.

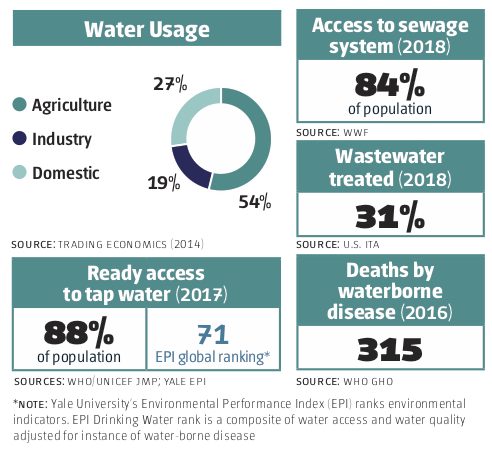

Colombia has long counted water as an abundant resource, experiencing roughly three times the global average of rainfall per country. But the geographic distribution of Colombia’s water is lopsided, with the large majority of fresh water aquifers located in the Amazon Basin where the population is sparse. Rural areas are notably underserved and 74% of coffee farmers surveyed cited droughts as a growing threat to their livelihood. Most of Colombia’s wastewater treatment is lacking due to a low number of basic treatment facilities, but systems like those in Medellín offer a model for the rest of the nation.

What the Government Is Doing

President Iván Duque has addressed water scarcity in specific regions by launching a $115 million plan to achieve universal water access in La Guajira by 2024, as well as the Bicentenary Water Pact to guarantee access to potable water in Norte de Santander. The government created the National Council for the Fight Against Deforestation, followed by the rollout of Operation Artemisa, a military-led strategy to end deforestation and protect water sources. Colombia’s water resources at the federal level fall under the Environment and Sustainable Development Ministry, which exerts weak oversight over 33 autonomous regional corporations that run regional environmental programs.

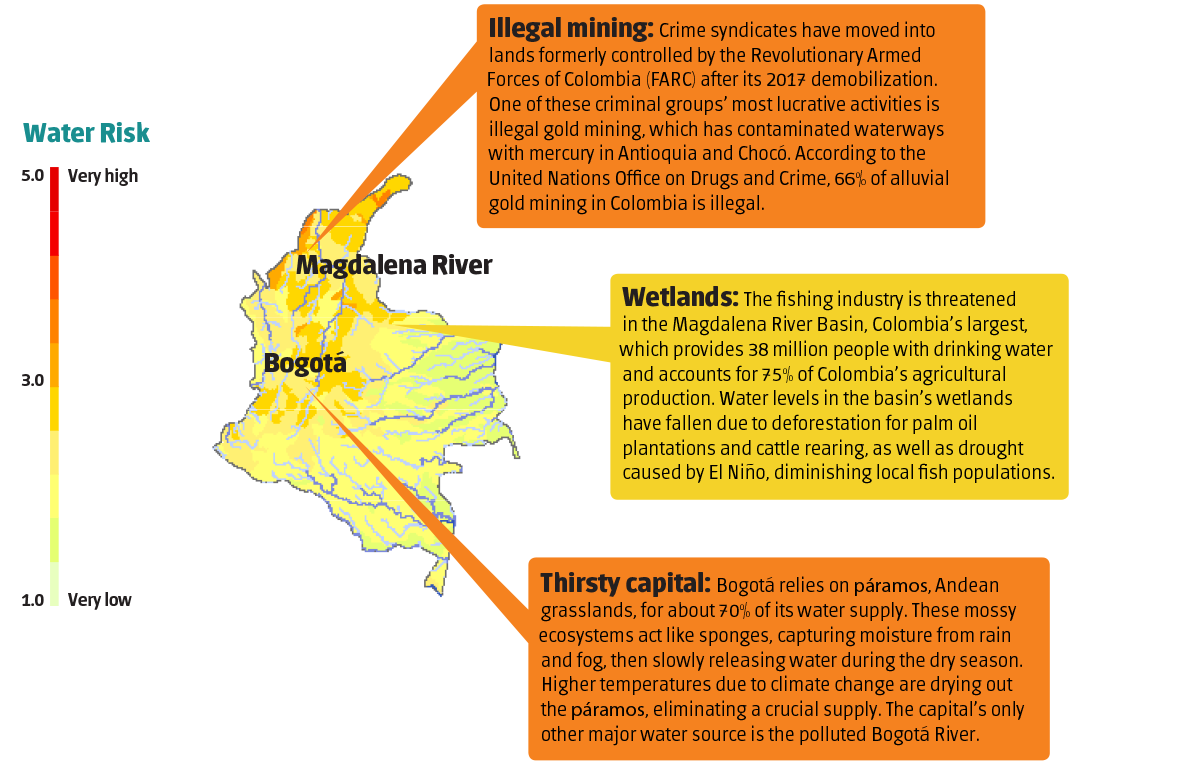

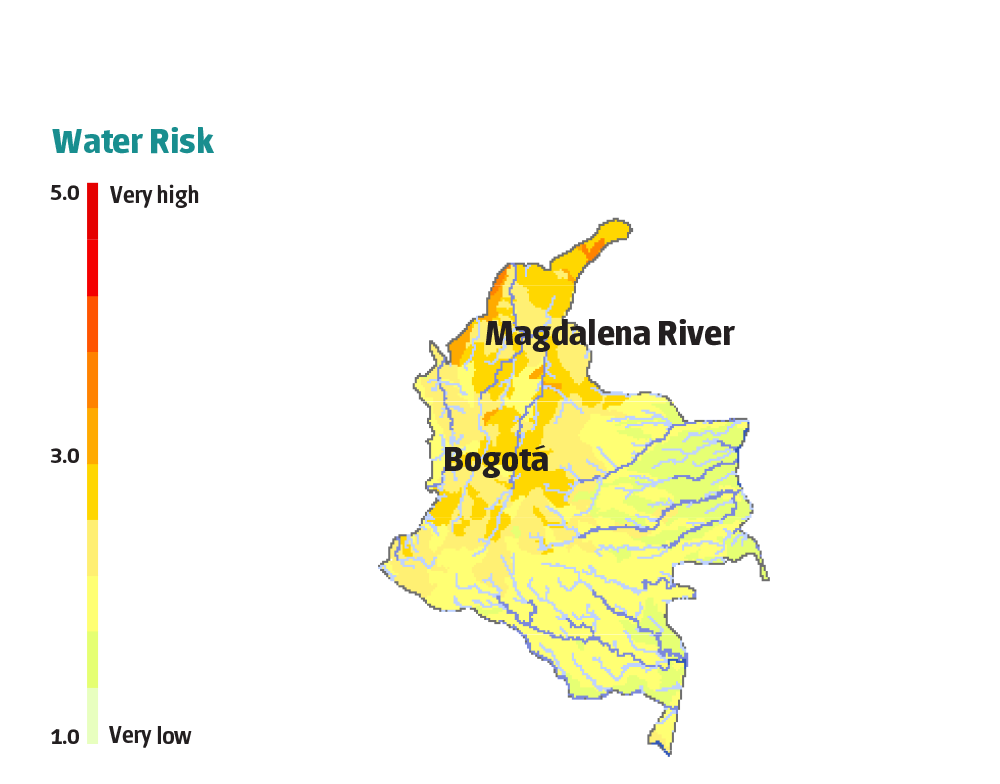

Colombia’s Water Hot Spots

Illegal mining: Crime syndicates have moved into lands formerly controlled by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) after its 2017 demobilization. One of these criminal groups’ most lucrative activities is illegal gold mining, which has contaminated waterways with mercury in Antioquia and Chocó. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 66% of alluvial gold mining in Colombia is illegal.

Wetlands: The fishing industry is threatened in the Magdalena River Basin, Colombia’s largest, which provides 38 million people with drinking water and accounts for 75% of Colombia’s agricultural production. Water levels in the basin’s wetlands have fallen due to deforestation for palm oil plantations and cattle rearing, as well as drought caused by El Niño, diminishing local fish populations.

Thirsty capital: Bogotá relies on páramos, Andean grasslands, for about 70% of its water supply. These mossy ecosystems act like sponges, capturing moisture from rain and fog, then slowly releasing water during the dry season. Higher temperatures due to climate change are drying out the páramos, eliminating a crucial supply. The capital’s only other major water source is the polluted Bogotá River.

Jump to: Peru | Mexico | Guatemala | Colombia | Chile

Venezuela | Argentina | Brazil | Full List