Brazil | Colombia | Costa Rica | Mexico | Paraguay | Venezuela | Cuba

See above for a breakdown of the region’s other 2018 transitions, or click here for the full list from our print edition.

Election date: May 27

Format: Two rounds. If no candidate receives more than 50 percent of votes in the first round, the two leading candidates will proceed to a run-off on June 17.

Humberto de la Calle, 71, former minister

Liberal Party

“We need the young people to put an end to hatred.”

How he got here: The elder statesman of the race, De la Calle has spent more than three decades in public life as a minister, a primary presidential candidate, and as vice president to former President Ernesto Samper (with whom he later had a falling out). In 2012 President Juan Manuel Santos tapped him to lead peace negotiations with the FARC, and in November he was chosen as the Liberal Party’s candidate for 2018.

Why he might win: He’s a good-natured centrist in a race that is sure to feature extreme — and off-putting — rhetoric. He knows the peace deal backwards and forwards, and is widely viewed as the candidate best placed to oversee its implementation.

Why he might lose: The peace deal. About half of the country opposed Santos’ agreement with the FARC, and no candidate is more tarnished by association (with it and with Santos) than De la Calle. Other candidates, particularly Fajardo, will offer strong competition for Colombia’s centrist vote.

Who supports him: The Liberal Party was long a dominant force in Colombian politics and is still the second-largest party in Congress. Preserving the peace deal is a top priority for many voters.

What would he do: He has said that implementing the peace deal is the most important task facing Colombia’s next president, but is also focused on reducing inequality and tackling Colombia’s competitiveness gap.

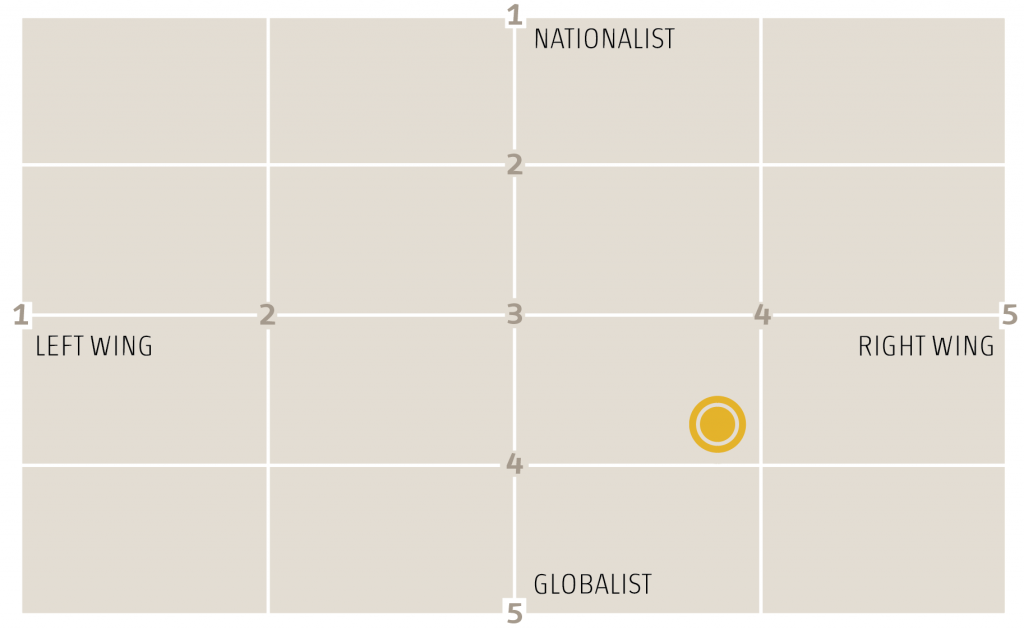

Ideology: AQ asked a dozen nonpartisan experts on Latin America to help us identify where each candidate stands on two spectrums: left wing versus right wing, and nationalist versus globalist. We’ve published the average response, with a caveat: Platforms evolve, and so do candidates.

AQ asked a dozen nonpartisan experts on Latin America to help us identify where each candidate stands on two spectrums: left wing versus right wing, and nationalist versus globalist. We’ve published the average response, with a caveat: Platforms evolve, and so do candidates.

Iván Duque, 41, senator

Democratic Center

“Diplomatic euphoria doesn’t guarantee the construction of peace.”

How he got here: He’s the son of a former governor, and served stints at the UN and the Inter-American Development Bank. Still just 41, he’s a rising star of the Democratic Center party, beating out four other “pre-candidates” for the right to carry the flag for former President Álvaro Uribe in 2018.

Why he might win: He talks like a centrist and is less polarizing than other candidates who opposed the peace deal. His selection to lead the Democratic Center makes him an instant front-runner. Some may call for him to run as vice president in a conservative coalition, but given Uribe’s weight in national politics, that outcome seems unlikely.

Why he might lose: Inexperience. He’s only been a senator for three years, spending much of his professional life in the sedate halls of U.S. universities and international institutions. Colombian politics get messy, and he’ll have to distinguish himself from other front-runners, like Vargas Lleras.

Who supports him: Uribe supporters and much of the “no” camp from the peace deal. If he runs an ideas-based campaign, and stays out of the mud, he could even sway some young independents.

What would he do: Duque has been critical of Santos’ economic policy, particularly a development plan that shifted focus away from infrastructure, mining and agricultural development. As with other pro-Uribe candidates, he wants to revisit or revise some parts of the FARC deal.

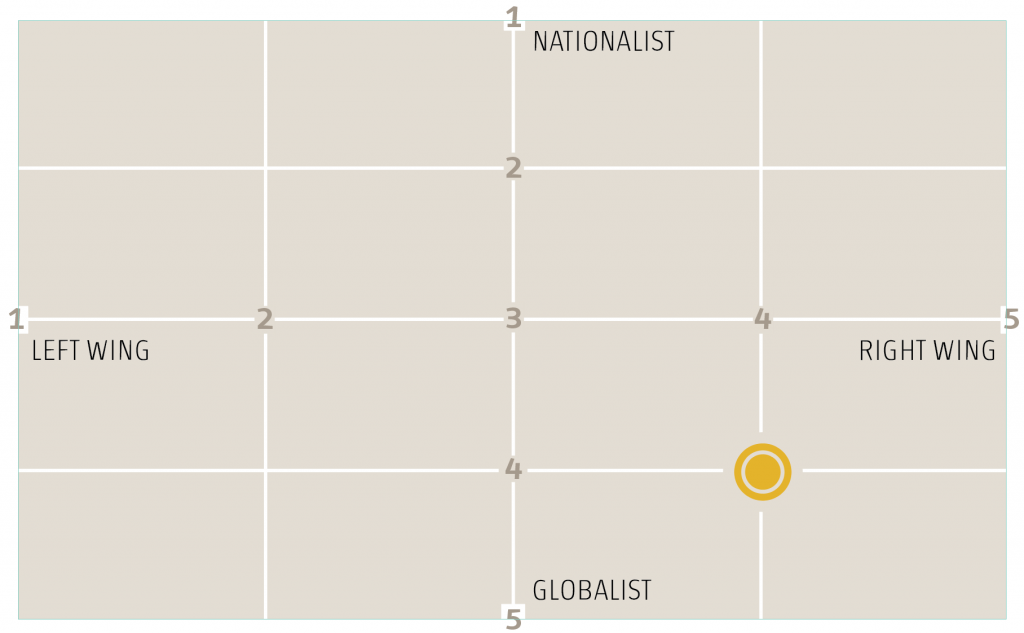

Ideology:

Sergio Fajardo, 61, former governor

Sergio Fajardo, 61, former governor

Citizens Commitment

“If courage (in the form of insults) is what people are looking for, that’s not me, because that’s not the kind of courage that Colombia needs.”

How he got here: A former math teacher and newspaper columnist, Fajardo didn’t enter politics until well into his 40s. As mayor of Medellín, he oversaw a big reduction in violence and carried out an ambitious — and internationally lauded — public works plan. From 2012 to 2016, he was governor of Antioquia, Colombia’s second most populous state. He’s now near the top of early polls, and will lead the “neither Santos, nor Uribe” coalition in 2018.

Why he might win: Seen as a clean, competent politician without strong ties to traditional power elites, Fajardo should find broad support among Colombians looking to reform — but not upend — the political hierarchy.

Why he might lose: Despite enduring popularity in Antioquia, Fajardo is still not well-known at the national level. His opponents will take the opportunity to paint him with a broad “leftist” brush that includes more radical figures — some on Twitter call him “FARCjardo.”

Who supports him: Some of his hometown crowd in Antioquia (which he’ll have to split with Uribe’s Democratic Center) and a large chunk of urban and educated voters.

What would he do: Middle-of-the-road economics, a push for transparency and a focus on improving education. Implementing the peace deal would be a priority — but not the driving force behind his government.

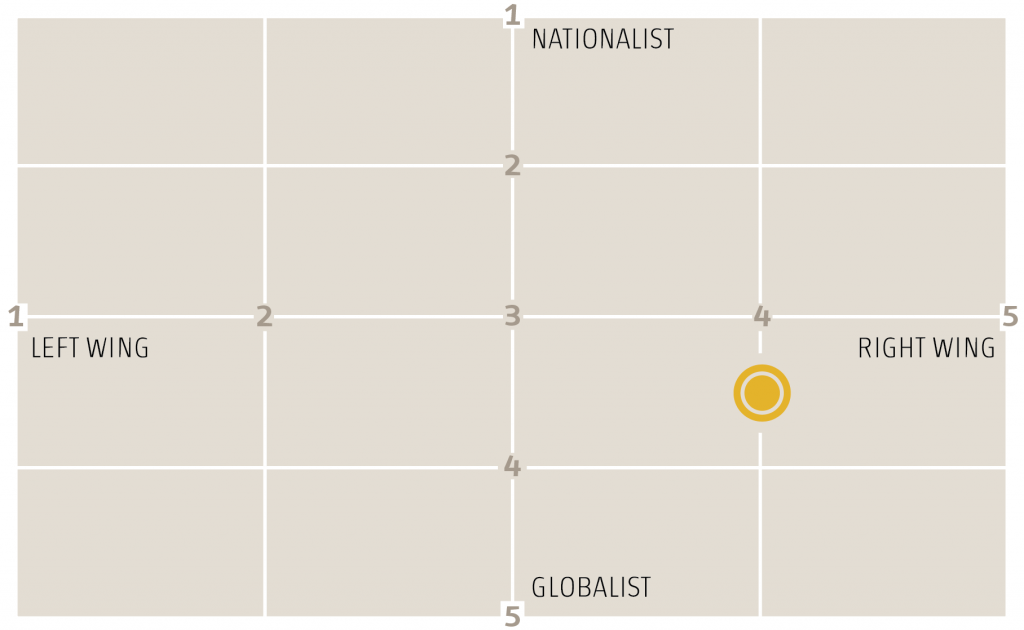

Ideology:

Gustavo Petro, 57, former mayor

Gustavo Petro, 57, former mayor

Progressive Movement

“The more I am attacked, the more support I get.”

How he got here: A former member of the left-wing M-19 rebel group, Petro played a role in its disarmament in the 1980s and the rewriting of the Colombian constitution in 1991. As a congressman he railed against corruption and the political elite, and came in fourth in the presidential race in 2010. Petro cemented his standing as a national figure with a controversial turn as mayor of Bogotá starting in 2011.

Why he might win: He’s an articulate populist and a charismatic anti-establishment candidate at a time when Colombians’ faith in public institutions is near an all-time low.

Why he might lose: Colombia’s two-round presidential system should put a damper on Petro’s presidential ambitions. Winning head-to-head against a more mainstream opponent would require him to connect with voters well beyond his base — which he has not done so far.

Who supports him: Lower-income voters across the country, who see him as their only real champion, as well as some young urban voters who are disenchanted with politics — and not put off by his guerrilla past.

What would he do: As mayor, Petro proved himself more a man of ideas than of execution; a poorly managed public takeover of Bogotá’s trash collection system led to his ouster. He advocates for agrarian reform, renewable energy, and social programs that favor Colombia’s marginalized classes.

Ideology:

This entry has been updated

This entry has been updated

Marta Lucía Ramírez, 63, former defense minister

Independent

“The FARC’s interest has been, and continues to be, to seize power.”

How she got here: No one can doubt Ramírez’s presidential bona fides. She was the country’s first — and still only — woman to serve as defense minister (under Álvaro Uribe). She’s also been trade minister, Colombia’s ambassador to France, and served in the Senate. In 2014 she earned more than 15 percent of the vote running on the Conservative ticket. Now an independent, Ramírez, Duque and former Inspector General Alejandro Ordóñez will compete to lead a conservative coalition into the first round.

Why she might win: She has a positive relationship with two influential ex-presidents (Andrés Pastrana and Uribe), and if she finds herself leading the coalition with support from other conservative forces — namely the Democratic Center — should could quickly become a front-runner.

Why she might lose: Duque is still the most likely candidate to lead the conservative coalition in May; Ramírez may have to resign herself to the vice presidency or a cabinet post.

Who supports her: She split from the Conservative Party but will still attract voters from the traditional center-right; she is more well-known — and viewed more favorably — than most other conservative candidates. There are plenty of Colombians who think it’s time the country had a woman president.

What would she do: She would seek a referendum on changes to the peace deal, particularly on points related to transitional justice. Like most of Colombia’s presidential hopefuls, she would look to make business-friendly reforms to the tax code, widen the tax base, and pursue foreign investment.

Ideology:

This entry was updated to reflect Ramírez’s Jan. 22 decision to participate in a coalition with other conservative candidates.

Germán Vargas Lleras, 55, former vice-president

Germán Vargas Lleras, 55, former vice-president

Radical Change

“I consider myself a man of the center … except when it comes to security.”

How he got here: Politics are in his blood. Vargas Lleras is the grandson of a former president and related to another. He was a minister and then vice president under Juan Manuel Santos, though he won’t have the president’s support in 2018. Vargas Lleras resigned in March to pursue what will be his second run at the presidency.

Why he might win: Electoral machinery and political savvy. He avoided coming down too far on either side of the peace debate, and has a reputation for getting things done. He’s a safe vote for business and establishment voters who aren’t defined by their support or opposition to the peace deal.

Why he might lose: He’s well-known and near the top of the polls, but that doesn’t mean he’s popular: Nearly 60 percent of Colombians have an unfavorable view of him, according to Gallup. More than most, his Radical Change party is under the microscope for corruption.

Who supports him: He has a strong base of support on the populous Caribbean coast and is well-liked by the business elite. Vargas Lleras and “the one Uribe chooses” will battle it out for Colombia’s center-right.

What would he do: Pro-growth, pro-business economics. He wants to make it easier for foreign firms to invest, focusing efforts on infrastructure and mining. He also hopes to streamline the country’s bureaucratic health care system.

Ideology: