This article is adapted from Americas Quarterly’s print issue on Venezuela after Maduro.

On a hillside in Southern France lies a lichen-speckled tombstone commemorating a distant and ephemeral realm, and the man who almost made it last: “Here Lies De Tounens, Antoine Orélie, First King of Araucanía and Patagonia.”

For a brief period in the 1860s, Tounens — a lawyer turned adventurer from the nearby town of Tourtoirac — united Mapuche tribes against the Chilean republic headquartered in Santiago. With the tribes’ blessing, Tounens established an independent kingdom stretching over the fjords, forests and frosted peaks of the southern cone of Latin America.

The rapid rise and fall of this kingdom is usually considered a footnote to Chilean history. Tounens is typically portrayed as either a nefarious agent of French imperialism or, in his native France, as a deluded and eccentric opportunist. His adventure was so audacious as to be preposterous. And besides, why would the indomitable Mapuche, who had refused to submit to the Spanish, appoint a lunatic foreigner as their king?

In recent years, Mapuche historians have attempted to answer this question from the perspective of their own politically astute ancestors. They’ve worked to restore Tounen’s reputation, and recast the Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia not as a madman’s fantasy, but as a bold ploy that could have redrawn the map of South America — and still may, by bolstering their current claims for greater autonomy.

Tounens first set foot on Chilean soil in 1858, at a vital juncture in the country’s history. The young republic’s control extended 300 miles south of Santiago to the Biobío River. But beyond its waters the Mapuche held sway.

True, the conquistadores had once established settlements farther south, but the Mapuche had destroyed them in the 16th century. The Spanish cut their losses, withdrew north of the Biobío, and signed a 1641 treaty with the Mapuche recognizing the river as the border between territories. By the 1850s, however, the uneasy truce was fraying and Chilean forces were militarizing the southern border.

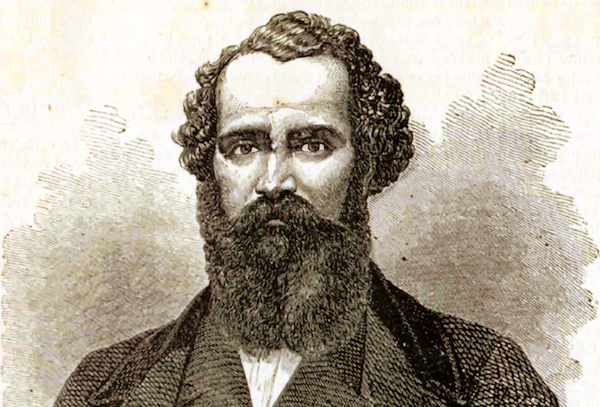

Antoine Orélie de Tounens (Araucanie.com)

Antoine Orélie de Tounens (Araucanie.com)

As a child, Tounens had read about the Mapuche — the “Araucanian Centaurs,” he called them — in the Spanish discovery novels he gobbled up. He “fell ill with geography,” in the words of his biographer, Armando Braun Menéndez, and believed that South America could bring him the adventure and purpose he craved.

After arriving in the Chilean port of Valparaíso, Tounens began to exchange letters with the revered Mapuche Chief Mañil. Together they hatched a plan. “Mañil had ruled Wallmapu, the Mapuche nation, for 60 years and he knew a Chilean invasion was imminent,” said Reynaldo Mariqueo, the chargé d’affaires of the kingdom, which continues in exile to this day and is now based in the U.K. “He told his people he had dreamed that a winka (foreigner) had been sent to save them.”

“Anything but crazy”

What help was a quixotic French lawyer to the Mapuche cause?

Under the Doctrine of Discovery, the dominant international law of the period, it was forbidden to annex lands and peoples ruled by a Christian monarch. A white European king could help the Mapuche gain recognition for their territory. “Chilean historians like to portray the Mapuche as savages, but it’s likely that Mañil, through his conversations with (Tounens), understood the implication of these laws,” Mariqueo told AQ. “He told the tribes of his dream to ensure their support for the plan.”

“The Mapuche were an independent nation and their leaders urgently needed international support before the imminent Chilean-Argentinian invasion,” said Pedro Cayuqueo, author of the recent bestseller, Historia secreta Mapuche. “In this context, the idea of being a French protectorate was anything but crazy.”

In 1860, carrying a green, white and blue flag he had designed for his kingdom, Tounens crossed the Biobío. With the consent of local leaders, he proclaimed himself King Antoine of Araucanía and Patagonia, drew up a constitution, and established a cabinet with Mañil’s son as minister of defense. That December he attended four separate coronation ceremonies, telling the attending Mapuche that “natural and international law empowers you to become a nation so that you can march forward toward progress at a steadier pace.”

It wasn’t to last. In 1861, rumblings of a French king in the south reached the ears of Cornelio Saavedra, the 40-year-old governor of Arauco province on the northern bank of the Biobío. Saavedra had been unsuccessfully lobbying the president to invade the south, and in Tounens he saw an opportunity to push his case.

In January 1862, following a tip-off from his own guide, Tounens was captured as he dozed under a pear tree, and hauled before Saavedra.

During his trial for disturbing the peace and illegally entering indigenous territories, Tounens defended himself on the basis that as a citizen of Araucanía and Patagonia he did not recognize Chilean laws. Narrowly escaping the death penalty through the intervention of some benevolent merchants, Tounens spent the next year in prison then a madhouse before being sent back to France.

Gone but not forgotten

Over the next 16 years he returned three times to Patagonia, but his attempts to recover his kingdom were thwarted by a lack of funds, chronic illness and increased attention from authorities.

Frustrated, poor and childless, Tounens took his last breath on the second floor of a stone house opposite Tourtoirac Abbey in 1878. With him died his dream of a Mapuche free state.

Saavadera used the threat of French invasion to secure presidential approval for a push south. Historians estimate that in the following years the Mapuche population fell 90 percent due to war, famine, disease and displacement. Saavedra became a revered Chilean hero, his name on streets, and his face on banknotes. Tounens was nearly forgotten.

But not quite. Today a new bronze bust of an older Tounens, shaggy of mane and beard, stands outside Tourtoirac Abbey. Inside a modest museum, the sad remnants of his impossible dream: old maps demarcating his austral realm, a dusty flag of the kingdom, the coins he minted and the medals he doled out.

There are copies of pamphlets from the period promising a “Nouvelle France,” in the late 1860s, when Tounens petitioned for funds and immigrants to settle his kingdom.

“At school, we were taught that (Tounens) was an enemy of Chile who wanted to colonize the south to make a French territory,” said Nelson Lobos Camerati, a director of the Historia Mapuche website.

The French attributed him no such importance. While Tounens achieved minor celebrity status in the 1870s, it was as a source of ridicule for high society. The cartoonists of the age portrayed him as wild-eyed and deluded, a sort of hapless and comic Rasputin.

Tounens remains one of the most elusive figures in Latin American history. His own memoirs are scattered and full of omissions, and focus more on legal arguments than on descriptions of his journey and or his motivations.

Nevertheless, the Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia survived, if barely, and is now seeing a resurgence of sorts. The crown and the government-in-exile still exist, passed down to chosen successors. In 1952 a French publicist, Phillipe Boiry, became prince regent and used the kingdom as leverage to win the Mapuche observer status in the UN’s Economic and Social Council.

“To create the mission, we had to argue before the council that we were an independent nation,” said Mariqueo, who worked on the project and travels regularly to Geneva to represent the Mapuche. “The kingdom was an important tool. It existed before the annexation by Chile and Argentina, and that is very important.”

—

Youkee is a journalist based in Bogotá