GEORGETOWN — A longstanding, deeply-rooted demand from Guyana’s civil society got a boost recently when President Irfaan Ali swore in the Constitution Reform Commission. This 21-member group will now review the country’s charter and legal foundation, including a crucial assessment of the electoral system. It’s a daunting task for any society—and one made more pressing and sensitive by Guyana’s ethnic-based political polarization.

But paradoxically, despite broad agreement that reforming Guyana’s constitution is necessary to resolve the country’s political dilemmas and strengthen its institutions, the Commission’s creation has been met with silence, if not apathy. And it’s not hard to see why: Past commissions have failed to yield substantial results in their investigation of issues like the 1980 assassination of political activist Walter Rodney, the debacle that unfolded during the 2020 election, a fire at a state-run school dormitory that claimed 20 children’s lives last year, or issues with public services and education.

Few in Guyana expect the process to make a difference this time around. Public silence reflects the widespread view that government leaders will not support significant changes to a political system that has worked in their favor. The long delays and missed deadlines in putting together the Commission have done nothing to dispel that notion.

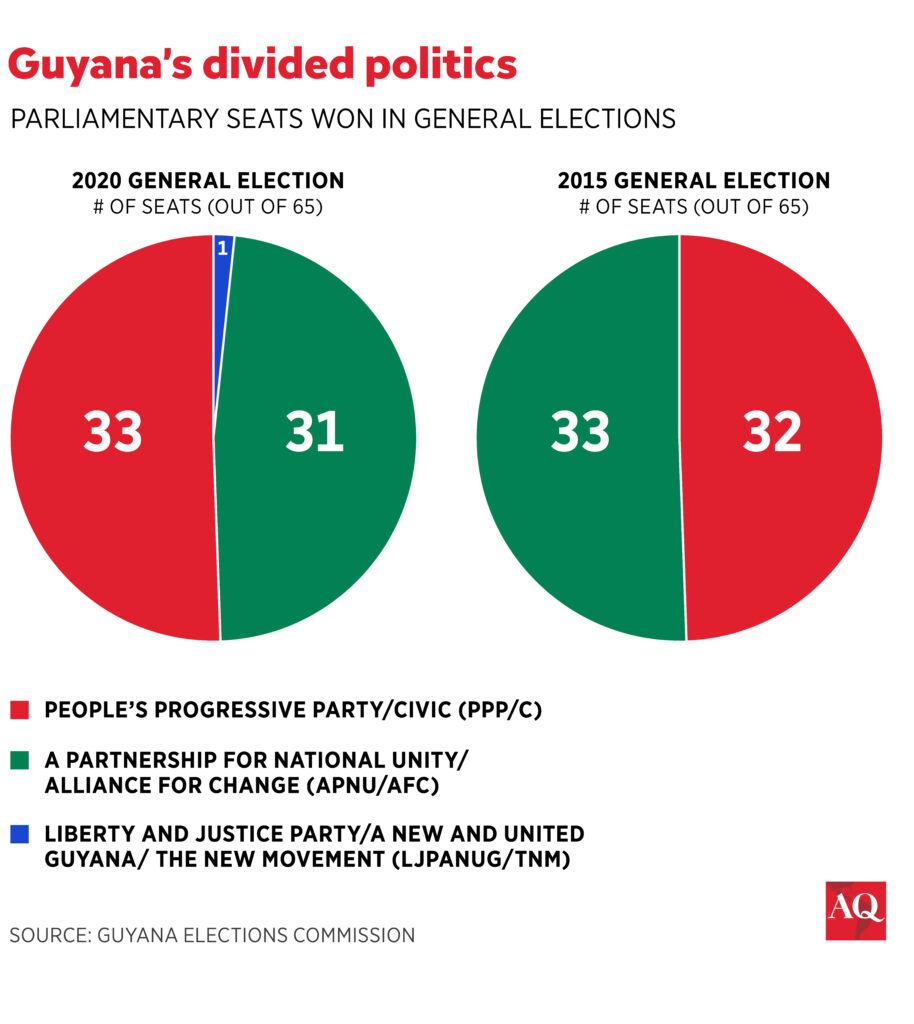

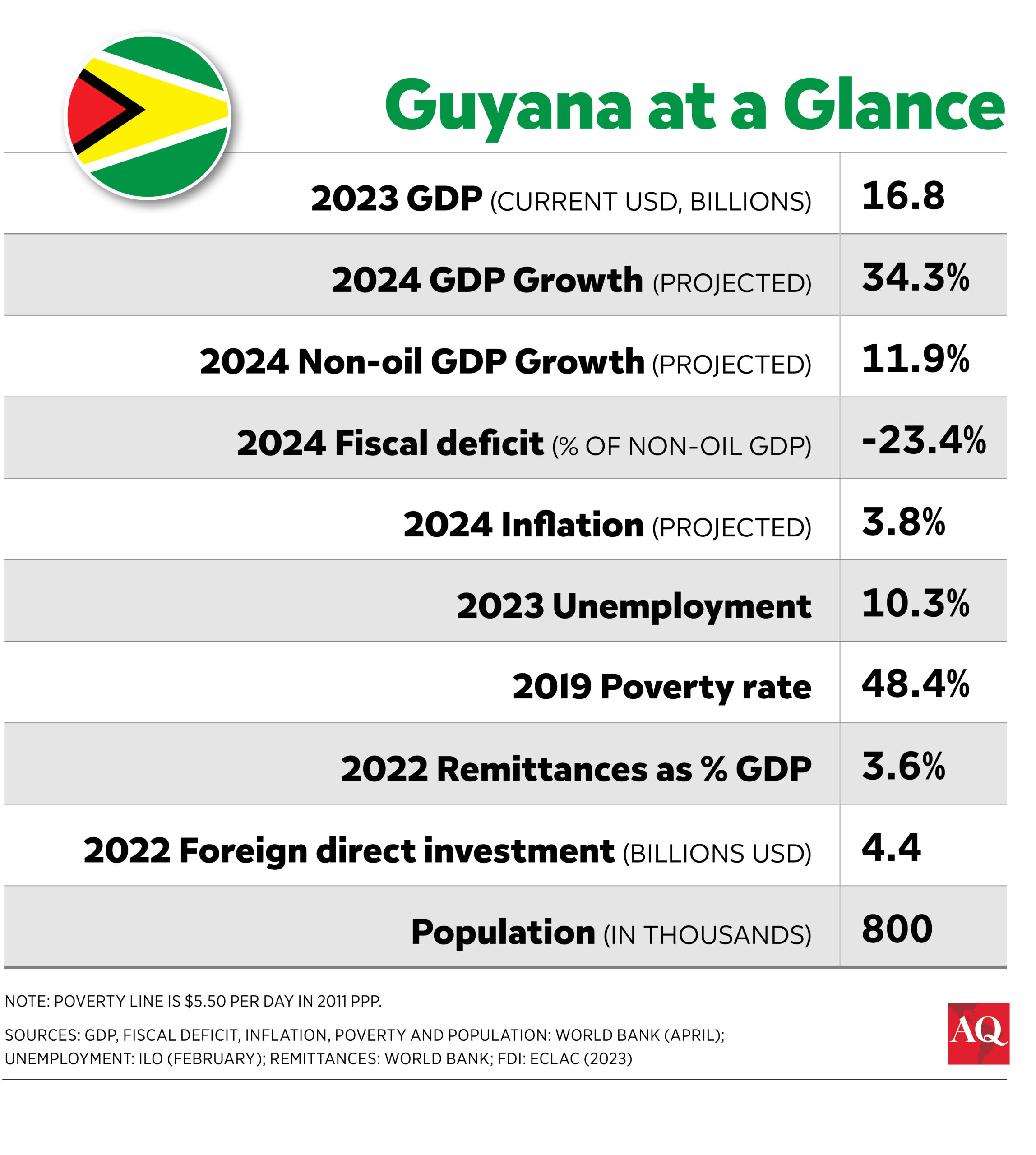

Guyana now faces a crossroads that requires meaningful action and careful consensus-building. The recent oil boom has raised the stakes on political power, exacerbating the risk of political instability. Major offshore discoveries of oil have located reserves of well over 11 billion barrels, establishing the country as one of the leading crude oil producers in the world in per capita terms and generating astronomical rates of GDP growth. However, a political system that gives the government—with a one-seat majority in the legislature—unrestrained control over natural resources breeds political discontent and instability.

Moreover, concerns that Guyana will experience the “resource curse” persist, as does economic hardship among the population. While the government boasts of presenting a $5.5 billion budget in 2024, the largest by far in the country’s history, equivalent to 26% of projected GDP, a teachers’ strike entering its ninth week indicates enduring social distress in the face of massive increases in the revenue generated by the oil industry. In these conditions, skilled professionals continue to look for emigration opportunities.

One Guyana

The government’s response has been to launch the “One Guyana” program to promote inclusion and equality. This program is no substitute for reforms to strengthen weak institutions and assert the rule of law. And the government’s response to criticism, for example over legislation establishing a Natural Resource Fund, undermines its credibility on these declared goals.

Critics also cite a lack of transparency, the government’s unregulated control over media, and the need for tighter campaign finance regulation and an agreed-upon code of conduct around elections. Some observers pose the merits of the parliamentary system, which Guyana used before 1964 and is used in many Commonwealth Caribbean countries with which this nation shares its historical past and political traditions.

The Carter Center and the EU have identified areas for improvement in the current governance system. The winner-take-all nature of government, the absence of adequate checks on the executive and its control of the legislature, the lack of direct connection and accountability of representatives to citizens, and the enforced loyalty of representatives to party leaders instead of the citizens that elected them are some of the factors inherent in the constitutional provisions that create the prevailing conditions of an elected dictatorship. As seen in recent elections, the excessive, unrestrained power of governments with slim margins inevitably breeds alienation and disaffection among close to half the population that feels that their interests are not being addressed.

Electoral reform

The agenda for constitutional reform is extensive, but the Electoral Reform Group (ERG), a civil society organization advocating for constitutional reform, which I co-founded in 2020, urges that electoral reform should come first. Guyana must change how it elects its leaders to establish governance structures that foster constructive political engagement consistent with a multi-ethnic, multicultural society.

In December 2022, the National Assembly passed government-proposed amendments to the Representation of the People Act, focusing on tightening the functioning of the existing election regulations and raising the penalties for violations. Electoral reform must address the governance architecture to establish a stabler, more constructive system that better uses the country’s considerable human and natural resources. It must strengthen inclusivity and the accountability of members of parliament to constituents, install adequate checks and balances among the executive, judicial, and legislative arms, and moderate the powers and immunities of the president in line with democratic norms. Such changes require amendments to the Constitution that can only be approved by a two-thirds parliamentary majority vote in favor or, failing that, a national referendum.

Still fresh in people’s minds is the 2020 national elections: it took a five-month standoff, court challenges, and a recount before the new government could take office. These events highlight underlying electoral and governance issues that have beset Guyana’s politics since the 1950s. Electoral reforms will unlikely be made before the next general election due in 2025.

Getting reform right

The Commission must submit its report to the National Assembly for final acceptance and determination of the reform program to be adopted. This means that the National Assembly—over which the ruling People’s Progressive Party has control—will be called upon to reform itself. It remains to be seen what level of statesmanship Commission members will display as national and party interests inevitably compete.

Advocating for electoral reform in Guyana is nothing new. Reforms have been introduced since the 1990s, but they must be more cohesive, better implemented, and repair a fragmented legislative framework to succeed. Highlighting the problem of poor implementation, the EU 2020 election observer report cites 26 election recommendations, of which as many as 19 remain to be implemented.

Guyanese citizens should appreciate the continuing relevance of reform and the need to get it right—and look to Caribbean neighbors, like Barbados, where the constitutional reform processes are in progress. A well-executed reform process would foster needed improvements and be a good example to other countries exploring ways to strengthen governance frameworks and generate inclusive economic growth for their people.