BRASÍLIA – Since the early 2010s, Brazil’s Congress has been steadily gaining power, and the country’s decision-making axis has gradually shifted from the executive branch toward the legislative branch. The latest sign of the change came as the president of the lower house, Arthur Lira, one of Jair Bolsonaro’s closest allies, quickly acknowledged Lula’s victory as Bolsonaro remained silent—but was even quicker to offer clear signs of the strength of Congress, making little secret of its future interests.

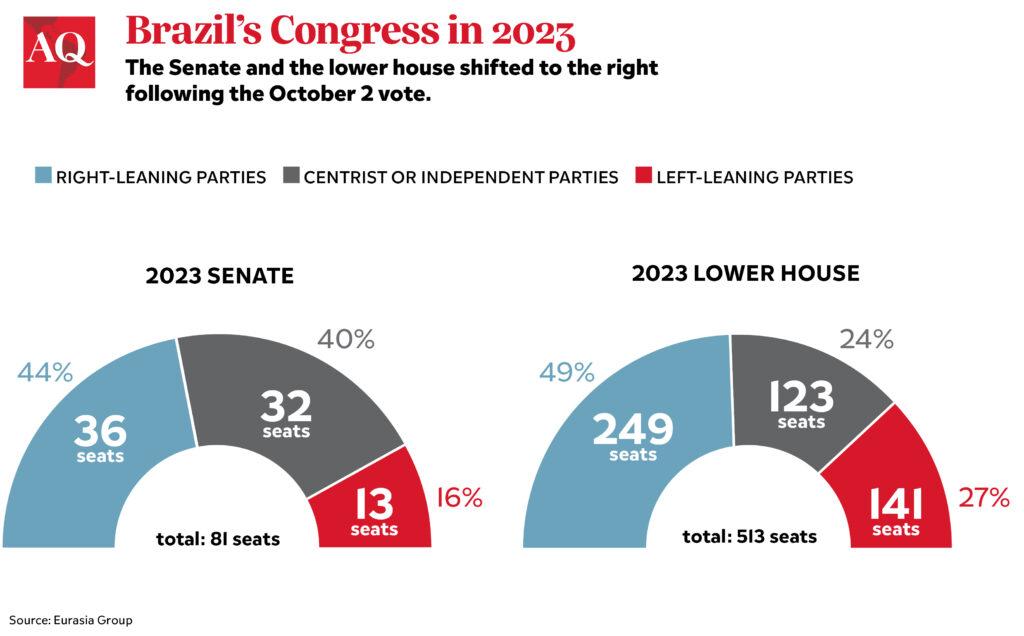

With 60% turnover in the lower house in this election and a strong conservative tendency among the 513 elected deputies, it’s clear the new Lula administration will have an enormous task in terms of building political stability next year. For his political survival, Lula must keep in mind several magic numbers of legislators whose support he’ll need to achieve governing stability.

The first magic number corresponds to the legislators whose support he needs to avoid impeachment. Approval of a request for impeachment requires the votes of 342 deputies in the lower house and 54 senators in the upper house. Thus, mathematically, Lula will need to secure a minimum of 172 votes in the Chamber of Deputies and 28 votes in the Senate to defeat any given request for impeachment. Looking at Lula’s coalition, composed of his Workers’ Party and a constellation of political allies, the picture is somewhat worrying: So far, the president-elect has about 123 votes in the Chamber. Widening his support in the lower house will be essential for his political survival.

What methods does the elected government have at its disposal to attract legislators’ support? A traditional one is handing out government jobs. Lula’s government could also attempt to build bridges of dialogue with deputies that do not consider or present themselves as heirs of Bolsonarismo, and who haven’t been given attention, or committee assignments, by Arthur Lira. The problem, however, is that Lira has specialized in actions and decisions that involve the largest possible number of parliamentarians. That becomes clear when we observe his ability to quickly advance and approve initiatives in an environment interspersed with crisis and instability.

In the Senate, in turn, whose importance is lower than that of the Chamber when it comes specifically to the dynamics of an impeachment process, President-Elect Lula will have at his disposal 27 votes among 81 seats—just short of the 28 he needs to stave off a potential impeachment, a fact that allows for dramatic twists and turns when we take into consideration that Lula made several campaign promises that are dependent on the support of Congress.

Enacting change

The set of second magic numbers Lula must keep in mind is the 308 votes in the Chamber and 49 in the Senate needed for reforms that require changes to the constitution. With his coalition well short of those figures, it seems unlikely the incoming government will be able to quickly reverse the constitutional reforms approved since 2016, when a PT government was last in power. Even if there is a lowering of expectations and Lula’s administration tries to achieve simple victories in Congress, the situation will still be somewhat complex. Lula will need 257 votes in the Chamber and 41 in the Senate to approve regular bills.

The arithmetic is tricky for a government that will take office laden with high expectations, but there is room for maneuver to contain potential threats—the most feared being that of impeachment. For Lula, the containment of this threat will necessarily involve building a dialogue with Arthur Lira, while waiting for the Supreme Court to rule on the constitutionality of the rapporteur’s amendments, known as the “secret budget” (orçamento secreto) that gave legislators free rein over budgetary allocations.

This legislative expedient, which helped build support for the Bolsonaro government within Congress, altered the balance of power between the executive and legislative branches in favor of the latter. It has given a high level of budgetary and decision-making autonomy to parliamentarians, without the requirement of any transparency mechanism. If this measure becomes the object of criticism from Lula’s government, problems will arise for the founder of the Workers’ Party.

Faced with this very unfavorable conjuncture and pressured by a strong legislative branch, between now and his inauguration in January 2023 Lula’s negotiation abilities will be tested to the very limit. Building legislative stability and ensuring his survival depends on the ability to co-opt support among center-right parliamentarians. These represent at least 155 votes distributed among parties such as the Brazilian Democratic Movement (MDB), the Social Democratic Party (PSD), the Republicans Party and the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB)/Citizenship Party. If this occurs, there could be a further gravitational effect that could bring even part of the almost one hundred congressmen in the pro-Bolsonaro delegation closer to the government.

Until February 2023, when the newly elected Brazilian Congress will be officially seated, Lira and, to a lesser extent, Senate President Rodrigo Pacheco, will be in a comfortable negotiating position in the face of a presidency that is seen by half of the electorate as unworthy of holding the office to which it was elected.

The window of opportunity and the ability to build alternatives are set against a difficult prognosis for the new government, and the perception that political and institutional instability will continue to prevail long after the end of the Bolsonaro administration. To reach the magic numbers, Lula will need to conjure a little magic of his own.

—

De Souza is CEO and founder of Dharma Political Risk and Strategy and a guest lecturer at Fundação Dom Cabral. He has an MA in International Relations from the University of Brasília and was a two-time fellow from the U.S. State Department.