Brazil’s social gap, which had seemed almost bridgeable in the 2010s, is now a widening fault line that threatens the country’s potential for growth unless long-term structural and educational reforms are undertaken.

The pandemic wreaked havoc on the lives of the world’s poor, turning a bad situation worse. For the rich across the globe the story was different. And in Brazil, the country that already boasted the title of the most unequal in Latin America, the World Bank’s Gini coefficient measuring inequality reached its highest number on record, 0.674, in the first quarter of 2021.

While earnings for the poorest 40% shrunk by a third in 2020, the top 10% of earners lost just 3% of their income. In the meantime, the stock market hit record highs, and commodity prices drove up measures of economic growth.

“It is a paradox,” said Marcelo Nery, director of the Center for Social Policies at the Fundação Getúlio Vargas, a Brazilian think tank and higher education institution. “GDP was better than expected, the currency appreciated, the stock market is up. Even formal job creation has improved.”

Only these indicators hide deeper problems. “Globally, we see investors’ risk appetite coming back, while investing is also getting cheaper in Brazil, bringing more people to capital markets,” said Laura Karpuska, an economics professor at FGV-São Paulo. “But the economic fundamentals have been worsening, and markedly so.”

A milder-than expected 4.1% contraction in GDP in 2020 was followed by a 1.2% increase in the first quarter of 2021 (comparing to the previous quarter), bringing Brazil’s economy back to where it was in 2016 — at the bottom of a deep recession. Unemployment is at a record high of 14.7%, and nearly 20 million Brazilians can’t find work or have given up looking. Even informal work is in short supply as COVID continues to spread across the country.

“The bulk of low-income jobs are in high-contact services, where we have yet to see a recovery,” said Otaviano Canuto, a former executive director at the World Bank and the IMF. “And there is a risk that changes in behavior, such as entertaining at home, could last much longer than the pandemic.”

Much of the optimism in Brazilian capital markets and in macroeconomic projections is being propelled by the agricultural and mining sectors. According to CEPEA, a research institute, the agribusiness sector grew 24% in 2020, and now represents slightly over a quarter of Brazil’s GDP. Brazilian exports of crops and meat totaled $100 billion last year, while mining exports increased by 31%.

But experts warn that the agroindustry does not have a multiplying effect on the economy as a whole. Commodity production is not labor intensive, and the more job-rich manufacturing sector has been shrinking since 2009. Meanwhile, inflation is on the rise, driving down the debt-to-GDP ratio — a measure observed by financial investors — but exacting a toll on consumers, especially the poor.

Emergency cash transfers of about $100, authorized by President Jair Bolsonaro’s administration, helped informal workers and the poor navigate the COVID-19 crisis—but hope evaporated when, despite the still-raging pandemic, the payments were discontinued at the end of 2020.

“We saw poverty levels fall by half last year, to 4.5%,” said Nery, “only to triple after the transfers stopped.”

By March 2021, 16% of Brazilians were at or below the poverty line. “We were generous, but not wise,” said Nery. “We did not prioritize testing or vaccines, and basically dismissed education altogether.”

The government’s spending on transfer programs reflects, for Nery, a predictable pattern in the lead-up to presidential elections. “Poverty numbers always fall, followed by a rapid increase,” said Nery, adding that the risk now is government attempting “grandiose solutions beyond our fiscal capacity.”

The diverging realities in the Brazilian economy—improving macroeconomic numbers and income at the top while more Brazilians fall into low-income classifications, including extreme poverty—are compromising future growth potential. “The multidimensional reality of this gap in income, wealth, access and representation is a major cause of our existing vulnerabilities,” said Karpuska.

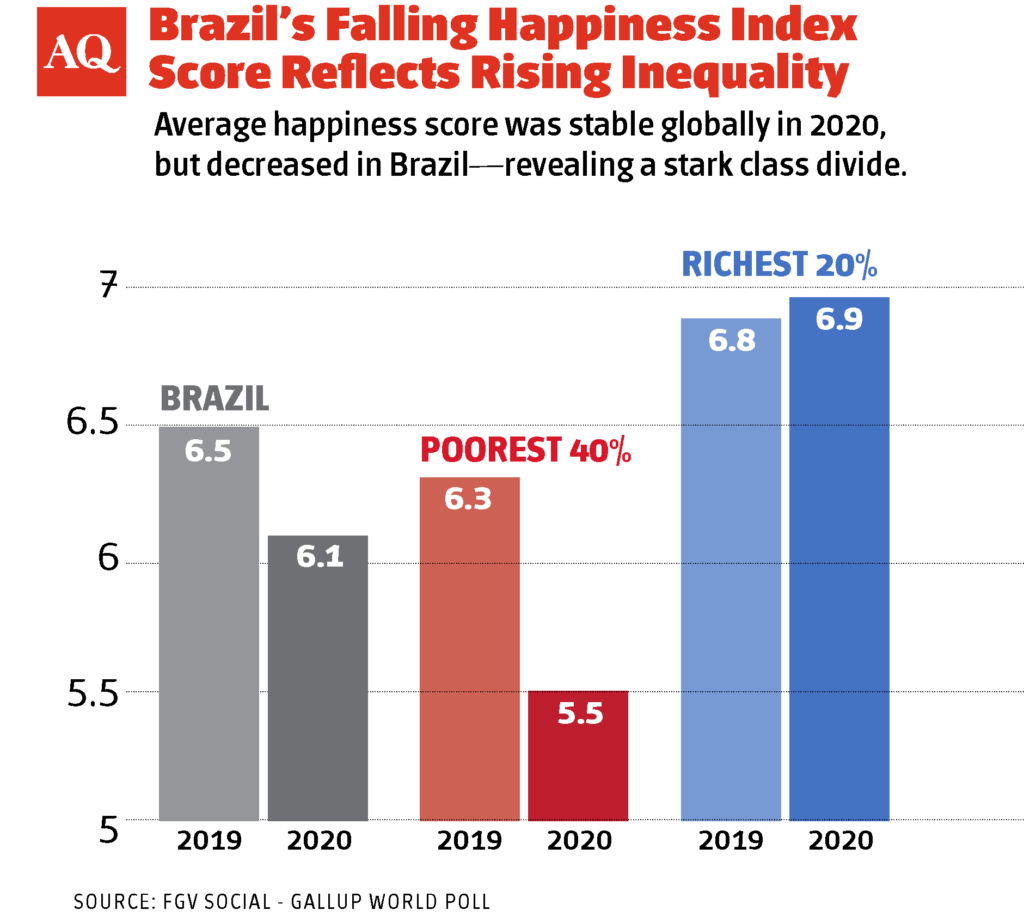

Inequality has even made an appearance on Brazil’s happiness index, which suffered the largest drop between 2019 and 2020 in a comparative study of 40 countries around the world — pushed by a sharp decrease of wellbeing among the poor.

Today, even the IMF warns that inequality severely impacts long-term growth and economic stability. “There is a direct link between masses that are able to consume and economic growth,” said Canuto.

Inequality’s social cost

Social gaps breed social unrest, as Chile and Colombia can attest. They also rob countries of the creative and productive potential of citizens that is a vital source of future wealth.

“Less human capital will mean less productivity and capacity to grow without triggering inflation,” said Karpuska. Future discrepancies are also likely to get a boost from pandemic-related school closings and education budget cuts, which primarily affected poor children. The percentage of young Brazilians neither working nor studying jumped from 20% at the start of the decade to 29% during the pandemic. Experts say that this pandemic generation, deprived of the benefits of education, will bring down productivity and impact the economy as a whole.

Bolsa Família, a cash transfer program for families in extreme poverty, has helped keep children in schools but, without job opportunities, families struggle to get out of the program. Canuto says only the children of current beneficiaries will have a chance to break the cycle of poverty — if the public sector can offer quality education and healthcare.

To combat the destructive force of inequality, Brazil needs comprehensive long-term policies, especially in education and digital inclusion. But amid an ongoing political and institutional crisis and on the eve of a presidential campaign, concerted action seems unlikely. Brazil’s share of the global economy has fallen from 4.3% in 1980 to only to 2.4% today. If the country continues to sabotage the future of its own people, this downward trend is sure to continue.