Now in its third year, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine continues to have ripple effects throughout Latin America and the Caribbean, which remains largely on the geopolitical sidelines when it comes to the confrontation. While European nations mull their next steps regarding the conflict, Moscow’s strategic aims in the Western Hemisphere are as clear as ever: ensuring the continuation of the region’s stance of “neutrality” and “active non-alignment,” as it has been variously termed.

In Russia’s strategic doctrine, the Western Hemisphere is a stage from which it can pose strategic threats to the United States, much in the same way that the U.S. and NATO purportedly pose strategic threats to Russia in Eastern Europe and Eurasia. Like clockwork, Russian aggression in Europe and Eurasia is often preceded by important diplomatic visits and occasional military escalation in LAC, as when it sent nuclear-capable military bombers to Venezuela for exercises in 2008 (before its invasion of Georgia), 2013 (before its invasion of the Crimean peninsula), and 2018 (after the poisoning of former Russian spy Sergei Skripal in the United Kingdom).

While the U.S. has had success in securing European support for Ukraine, it has met with stronger resistance in the Western Hemisphere. In perhaps the region’s best example of overt support for Ukraine—Ecuador’s short-lived agreement to trade old Soviet equipment to the U.S. in exchange for a $200 million assistance package—a Russian pressure campaign quashed the deal within weeks by cutting off banana imports valued at $800 million annually and instilling fear that these actions would rope the region into a wider conflict.

Latin America’s traditional stance of non-intervention has meant that regional governments have taken positions of “neutrality” and “non-alignment” on the war in Ukraine—stances that suit Russia’s hopes of ensuring that one of the world’s most democratic regions remains on the margins in its support for values of democracy and sovereignty. True, many Latin American and Caribbean countries have voted in favor of United Nations resolutions condemning Russia’s invasion—but most have gone no further. Some leaders have also taken actions that seem to contrast with their UN votes—such as Brazil’s Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who has ascribed blame to Ukraine for Russia’s aggression, or Mexico’s Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who raised eyebrows by inviting Russian troops to march in the country’s Independence Day parade held last September.

Before Russia’s invasion, the country used frequent diplomatic engagements in the Western Hemisphere to mitigate its isolation. Days before the unprovoked aggression, Russian visits by then-Deputy Prime Minister Yuri Borisov focused on military collaboration with its authoritarian allies, Cuba and Venezuela. Diplomacy appeared to lay the groundwork for full-throated support from these countries, but just as importantly, reticence to get involved among others. Russian officials such as Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov have frequented multiple regional capitals since the invasion, including Brasilia.

Economic pressure points

Russia has also partially managed to defang Western sanctions by relying on Latin America’s largest economies as continuous sources of hard currency. Last December, Russia exported the largest amount of oil since the beginning of the war to places like China, India, and Brazil—in fact, Brazil surged its purchases throughout 2023 to become the top buyer globally of Russian diesel. Several countries in the region, especially Argentina and Brazil, remain important export markets for Russian fertilizer, while Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, and Peru remain reliant to a lesser extent.

Russia’s political capital, earned through diplomatic engagement and by appointing experienced Russian ambassadors to every post in the region, demonstrates the importance the Kremlin places on the United States’ closest neighbors—and a level of interest compared to which the U.S. itself often falls short. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov just completed a visit to LAC, rounding out his tour with another stop in Brazil for the G20 foreign ministers meeting—his second visit to Brazil in less than a year. On Lavrov’s 2023 visit, he thanked Brazil for its statements on Ukraine’s alleged culpability for the war, emphasizing the two countries’ “similar approaches” to the conflict and the mutual desire to build “a more democratic … world order.” Lula has even stated his desire to host Russian President Vladimir Putin at the G20 Summit in November despite an outstanding warrant for his arrest by the International Criminal Court. Also, Lula will enthusiastically attend the BRICS annual summit in Moscow when Putin hosts it in October of this year.

Marking a sharp divergence from his counterparts in Brasilia, Bogotá, and Mexico City, it is important to note Argentine President Javier Milei’s intention to hold a summit of LAC countries that support Ukraine and reject Russia’s aggression. It still remains to be seen who actually attends the planned gathering.

The social media presence

Russia has sought to solidify the region’s non-aligned stance on Ukraine and to boost regional support for a fairer, more just multipolar world that displaces U.S. hegemony. By leveraging social media platforms and traditional media outlets alike—its RT news platform’s Spanish-language account on social media network X currently has 3.5 million followers—Russia seeks to justify its aggression as a natural response to what Russia views as intervention by the West. In the immediate wake of Russia’s invasion, hashtags referring to the need to “abolish NATO” trended regionally, including in major non-NATO countries Argentina and Brazil, and in Colombia, the only NATO global partner in the region.

There has long been support in Latin America for non-aligned and even anti-NATO positions. But the war in Ukraine led to an explosion of disinformation seeking to discredit the U.S. and its allies. The low cost of disinformation campaigns, and the ease of dissemination across platforms, allows Russia to normalize and magnify the reach of anti-West rhetoric and fringe conspiracy theories about the war in Ukraine. For example, disinformation campaigns following Russia’s disinformation patterns have accused Kyiv of staging actors to look like corpses, arguing the United States and NATO “planned the war in Ukraine,” and most recently, suggesting that Ukraine has been selling weapons to Hamas.

While it is difficult to assess the level of influence these campaigns have on the region’s many social media users, these disinformation campaigns sow skepticism and obfuscate the clarity of international law principles like sovereignty and territorial integrity violated by Russia’s invasion. As the Russia-Ukraine conflict enters its third year and a period of attritional warfare sets in, with few exceptions, Russia has Latin America and the Caribbean right where it wants it.

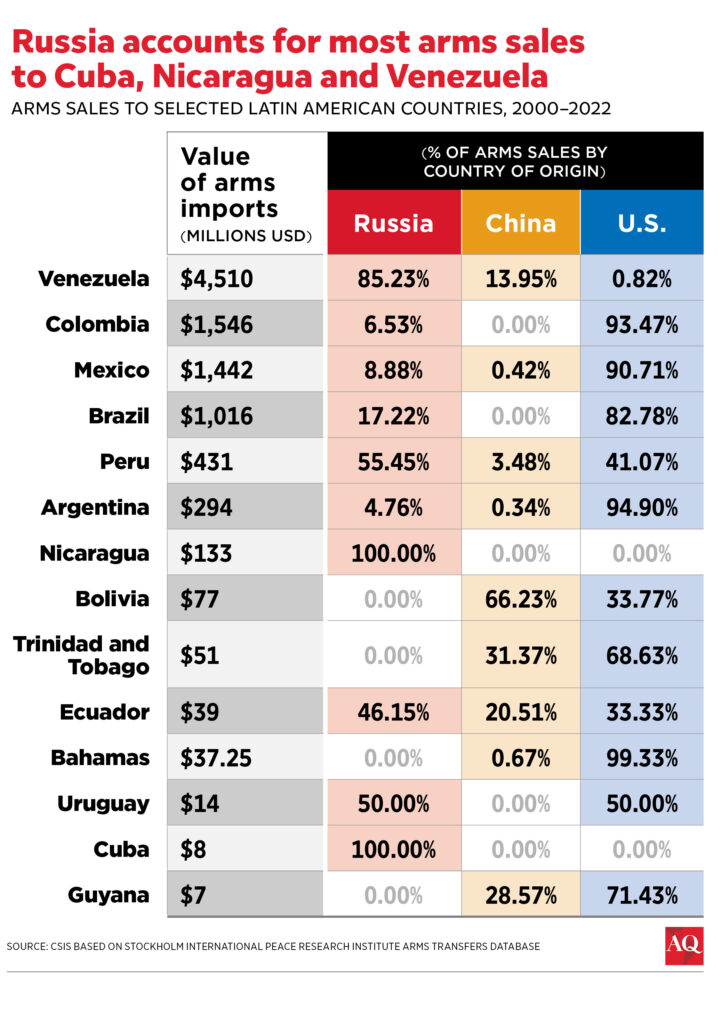

At this time, the governments of Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela are on Russia’s side, both rhetorically and in continued economic relations. Meanwhile, much of the rest of the region would prefer to discuss other global challenges and feels the West’s incessant focus on Ukraine to be self-serving and hypocritical. The result is that one of the world’s most democratic regions has chosen not to flex its muscle in support of Ukraine and its shared values.