This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Latin America’s ports | Leer en español | Ler em português

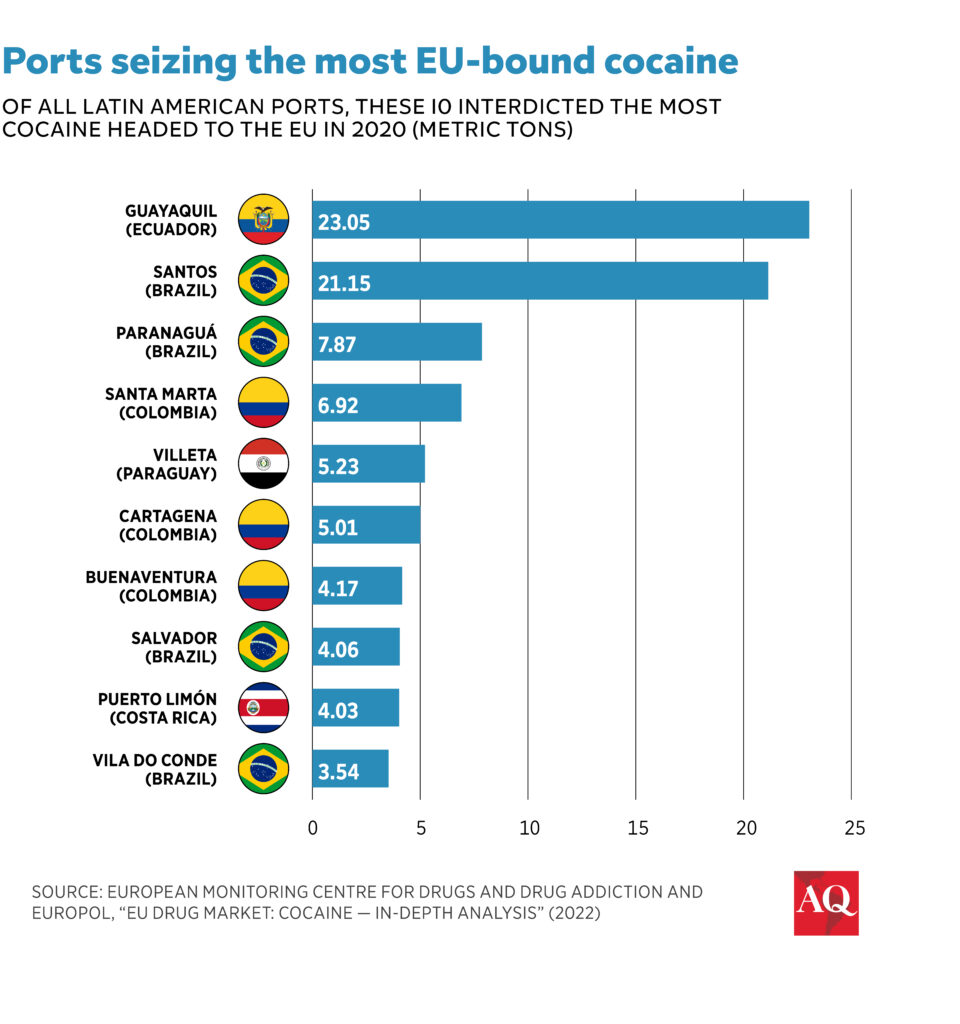

Latin America ’s ports face an array of security challenges, from narcotics to cyberattacks, often with national implications. For example, Ecuador’s recent explosion of gang-related violence has been fueled by drug gangs disputing control of Guayaquil, the country’s largest port—and city. Chile’s recent spike in violent crime is also partly related to activity at its ports.

Here, AQ has collected five recommendations for improving security at ports in the Americas, based on conversations with sector experts and executives.

Shore up cybersecurity.

Significant, costly cyberattacks have already struck a range of ports in the Western Hemisphere, according to a 2021 report on maritime cybersecurity by the Organization of American States (OAS). Ports have become attractive targets due to their rapid digitalization and automation and their increasingly important role as hubs for logistics data.

Cyberattacks on logistics hubs are ever more common, a 2021 ECLAC study shows. Assaults on ports often involve ransomware, which disrupts operations so that criminals can solicit a ransom to restore them. The NotPetya ransomware attack in 2017 affected all of Danish shipping conglomerate Maersk’s business units and its operations in several Latin American countries—and led to an estimated $300 million loss, according to ECLAC analysis.

To defend themselves, ports need to implement the same stringent cybersecurity standards as other digitized critical infrastructure. This means they should have cyber incident response plans in place, conduct regular drills and exercises, and establish firm data security protocols. This is especially important given that international rules on maritime cybersecurity still lag behind the severity and immediacy of port vulnerabilities, the OAS report concluded. Training personnel “is one of the most cost-effective and consequential steps a maritime organization can take” to reduce cyber vulnerabilities, the report said.

Don’t rely on reputation alone.

Reputations can be misleading. Sometimes, ports with reputations for security problems are undertaking efforts to improve, while ports with safer reputations are sleeping on risks.

In fact, criminal organizations sometimes target ports with “clean” reputations precisely because this can lower the chance of getting caught, a 2022 study in the journal Trends in Organized Crime showed. “Argentina, Chile and Uruguay are countries with clean reputations that do not activate the alarm system,” which is partly why they have seen an increase in drug trafficking in recent years, write authors Carolina Sampó and Valeska Troncoso.

Deploy technology to better track containers.

It’s crucial to create visibility in the supply chain as early as possible, said Gordon Wilmsmeier, professorial chair in logistics at Universidad de los Andes School of Management and director of the Hapag-Lloyd Center for Shipping and Global Logistics at Kühne Logistics University in Hamburg. Colombia, for example, has deployed a commonsense best practice: “Almost 100% of the trucks that take containers to or from the port are actually obligated by the insurance companies to use GPS,” Wilmsmeier told AQ. GPS allows mechanisms like geofencing, which creates a virtual boundary around a specific location, enabling container tracking in real-time. Technologies like blockchain could also improve cargo traceability, according to a 2023 report from Prosegur, a multinational security contractor.

Build anti-corruption measures.

Whistleblowers and other anonymous reporting mechanisms help identify corruption issues, and stakeholder collaboration contributes to resolving them. In Argentina, shippers have used the Maritime Anti-Corruption Network’s (MACN) anonymous incident reporting mechanism to disclose that officials were frequently soliciting bribes at ports to allow goods to pass inspection.

MACN, which represents over 200 maritime companies, brought government, civil society and private sector stakeholders together in 2015 to develop solutions collaboratively. The issue was addressed holistically, with a new regulatory framework, enhanced training for inspectors, and a new IT system to track inspections.

By 2019, MACN reported that the bribery solicitation in Argentina had fallen by 90%. “That cycle doesn’t happen overnight,” Cecilia Müller Torbrand, MACN’s chief executive officer, told AQ. It’s especially important for international organizations to develop solutions in consultation with local officials and businesses, she said, so that those solutions stick; without their buy-in, enforcement can become impossible. Often, it’s a matter of listening to local priorities and economic goals, and showing how transparency efforts can help reach them, Müller Torbrand added.

Improve cooperation and information exchange.

A 2022 study in Maritime Economics & Logistics found that “ports tend to compete against each other rather than collaborate” and that public policy doesn’t do enough to facilitate cooperation.

European officials have taken note, bolstering contacts with their Latin American counterparts amid the recent boom in the transatlantic cocaine trade. They’ve built momentum over the past year that is already making waves. Mayors and port authorities from Antwerp, Hamburg and Rotterdam visited Colombia in January to cement cooperation and exchange views on security measures with local government officials as well as port authorities from Ecuador and Peru. In February, Germany and Brazil signed an agreement to fight organized crime and drug trafficking. Last year, the EU launched EL PAcCTO 2.0, a €58.8 million program open to all Latin American and Caribbean countries to address transnational organized crime, alongside a European Commission investigation of the vulnerabilities of Guayaquil’s ports.

Sweigart is an editor at AQ

Brown is an editor and production manager at AQ

Rendon is an editorial assistant at AQ