This article is adapted from AQ’s latest issue on China and Latin America | Ler em português | Leer en español

BRASÍLIA — Early in his presidential campaign, Jair Bolsonaro took to the floor of Congress to angrily denounce what he called a “crime against the nation.”

He warned that China was acquiring too much control over Brazil’s niobium, an obscure but valuable mineral that can be added to steel to make it lighter and more resistant. Brazil has more than 85 percent of world reserves, and Bolsonaro said that if properly harnessed it could make “us one of the most prosperous nations in the world … We can’t let China come in here and buy up land, buy niobium, as if it were just another mineral! No!” he thundered, standing in front of a Brazilian flag. “That’s like giving the Chinese billions of dollars!”

But now as president, Bolsonaro is discovering just how difficult it is to separate niobium and other commodities from China’s tight embrace. The company that accounts for most of Brazil’s niobium production, Companhia Brasileira de Metalurgia e Mineração (CBMM), depends on exports to international steel companies. “China accounts for more than (half) of world steel production and we couldn’t be outside this main market,” Eduardo Ribeiro, the company’s chief executive, told AQ in an interview. Although Brazil’s Moreira Salles family owns a controlling interest in CBMM, five Chinese steel companies — Bao Steel, CITIC, Anshan Iron & Steel, Shougang and Taiyuan Iron & Steel — acquired a 15 percent stake in 2011. Bolsonaro vehemently criticized that deal as well. But in practice it has benefited all parties, helping the Chinese guarantee future supplies while allowing CBMM to shape future applications of niobium-based steel alloys in sectors such as construction, motors and oil and gas. Ribeiro described the deal, which saw Japanese and Korean steel groups buy another 15 percent of CBMM’s shares, as “strategic.”

The connections have paid off in other ways. Partly because of a change in Chinese regulations requiring builders to use stronger steel girders, sales of ferro-niobium ingots — one of CBMM’s most popular products—surged by 26 percent in 2018. The CBMM mine and smelting installations in the former spa town of Araxá were busier than ever, with the company’s 2,000 workers operating at full capacity. Ribeiro sees space for further expansion and outlined plans to invest 450 million reais (about $120 million) in both 2019 and 2020, up from 300 million reais in 2018.

A niobium smelting operation at CBMM.

A niobium smelting operation at CBMM.

The niobium story epitomizes a much broader dilemma for Brazil’s new government. As a candidate Bolsonaro, nicknamed the Tropical Trump, made it clear he wanted to realign foreign policy, establish closer ties to the United States, and distance Brazil from its growing links with China and other emerging powers. Anti-China rhetoric dovetailed neatly with the campaign’s stridently anti-leftist themes. Olavo de Carvalho, a U.S.-based Brazilian philosopher and an intellectual guru to the Bolsonaro family, suggested that cozying up to China formed part of a broader “cultural Marxist” trend — that 14 years of Workers’ Party rule had pulled the country away from the conservative values embraced by its population in both domestic and foreign policy.

In February 2018 Bolsonaro became the first presidential candidate to visit Taiwan since Brazil recognized the People’s Republic in the early 1970s. During the campaign Bolsonaro portrayed China as a predatory economic power, famously saying that Beijing is not just “buying in Brazil — it is buying Brazil.”

Chinese diplomats and other officials started to worry. “There were some strong declarations and this caused a lot of concern in China,” said Reinaldo Ma, a Brazilian lawyer with São Paulo-based Tozzini Freire, whose clients include some of China’s largest investors in the country.

Now is the moment of truth: Will Bolsonaro really turn away from Beijing? Or is the relationship already too deep, making a confrontation too painful? Other Latin American leaders who have tried to redefine their countries’ relationships with China, namely Argentina’s President Mauricio Macri and Ecuador’s Lenín Moreno, have seen how difficult it is in practice. But no other country has the sheer size — and therefore, the bargaining power — of Brazil. And that’s why Bolsonaro’s actions are being closely watched throughout the region: If Brazil can’t change the dynamic with China, then perhaps no one can.

But it’s also true that Brazil remains immensely fragile in the wake of its 2015–16 recession, with unemployment above 11 percent. Can the government afford to alienate a major investor and trading partner? The relationship has already suffered: Direct Chinese investment in Brazil fell from $11.3 billion in 2017 to just $2.8 billion in 2018, a drop some analysts attributed to uncertainty over the president’s comments during the campaign. Worried by the dynamic, several powerful lobbies — including agribusiness and the military — have pushed Bolsonaro to moderate his rhetoric now that he is in office.

There were signs by late March that this more moderate faction was prevailing. Bolsonaro stunned many Brazilians — including some of his top aides — when, standing next to China’s ambassador, he announced a trip to Beijing later this year. But some people close to the president insisted to AQ that there were still specific plans to drive the two nations apart. “Better to talk softly, and push them out of the infrastructure programs and the key privatizations,” one said. The battle for Brazil is just getting started.

Soy, Energy and Counting

Pressure to strike a more pragmatic stance has come from some of Bolsonaro’s staunchest supporters. Pedro Cervi, a 55-year-old agronomist from Curitiba in southern Brazil, has since the early 1990s owned 28,000 hectares of land in a booming northeast region of Brazil best known as Matopiba. Cervi, who grows maize, cotton and above all soy, exports 80 percent of his harvest to China, with produce carried by trailers up from his farm to the port of São Luis in Maranhão state. “China is really important for Brazil, especially on these new frontiers,” he told AQ.

Soy is Brazil’s largest crop, and farmers like Pedro Cervi were firmly behind Bolsonaro’s election.

Soy is Brazil’s largest crop, and farmers like Pedro Cervi were firmly behind Bolsonaro’s election.

Like many other big farmers, Cervi voted for Bolsonaro in last year’s election, but he is hoping that nothing will be done that hurts his business. “It would be irrational to damage our biggest trade partner. Bolsonaro was my option but his thinking on (China) was a bit hasty. He wasn’t well-informed.”

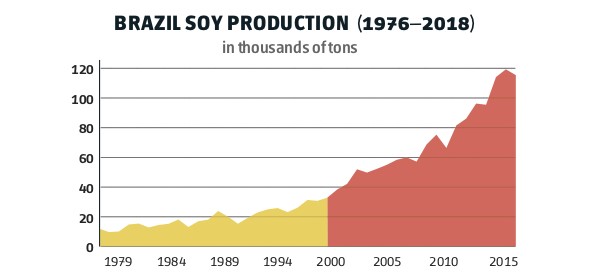

SOURCE: CONAB

SOURCE: CONAB

Meanwhile, Chinese investors have smartly paved the way for a détente — by learning from the backlash that followed their earlier investments in Latin America and Africa. Chinese companies operating here no longer try to import workers from home. The businesses acquired by China in recent years typically retain Brazilian management, staff and brand names. Very often the only sign that a Brazilian company is China-controlled is the regular video meeting with Chinese staff. Over the past few years, Chinese investors have increasingly come to prefer directing resources to brownfield businesses through mergers or acquisitions rather than investing in start-ups (so-called greenfield operations). The State Grid Corporation of China’s successful $4.1 billion purchase in 2016 of a controlling stake in the Companhia Paulista Força e Luz (CPFL), an energy generation and distribution company, was one of the largest of these deals. You have to look hard to find any visible sign of State Grid in its headquarters in downtown Rio de Janeiro.

The focus of China’s investment interest is broad. New technology giants such as Tencent, a micropayments and gaming company, and Didi Chuxing—a competitor to the ride-hailing giant Uber — are increasingly prominent. But energy has become particularly significant. Last year, China National Petroleum Corporation—one of China’s four giant state oil companies — bought a 20 percent stake in the Comperj refinery in Rio de Janeiro state, allowing work at the facility to resume three years after it was interrupted at the height of the Lava Jato scandal. In many cases, Chinese companies have been willing to accept much lower returns than other foreign players, taking a strategic long-term view of their investments. Rubens Sawaya, professor of economics at the Catholic University of São Paulo, cited a recent case in which the Chinese construction giant Sany financed its clients with interest rates that were “almost negative.”

China overpaid as much as 30 percent for CPFL, the energy company, according to Adrian Landgrebe, a London-based fund manager who specializes in Latin American stocks. In 2015, State Grid outbid international competition to win a $2.2 billion contract to build a 1,550 mile (2,500 kilometer) transmission line from Belo Monte dam in the Amazon to Rio de Janeiro. Why the generosity? China sees its electricity investments as part of a broader global plan, known as the Global Electricity Interconnection , which aims to develop a global electricity grid. Similar in character to the Belt and Road Initiative, it enjoys the backing of the Chinese government and chimes with the shift under President Xi Jinping to a more assertive Chinese foreign policy. Bruno Maçães, an author and former Portuguese diplomat, in a recent book, said it is “aimed at shaping China’s external environment rather than merely adapting to it.”

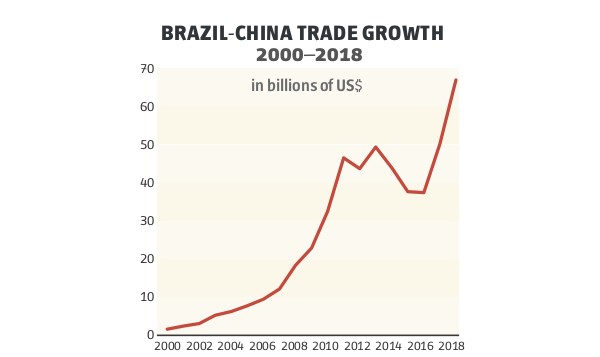

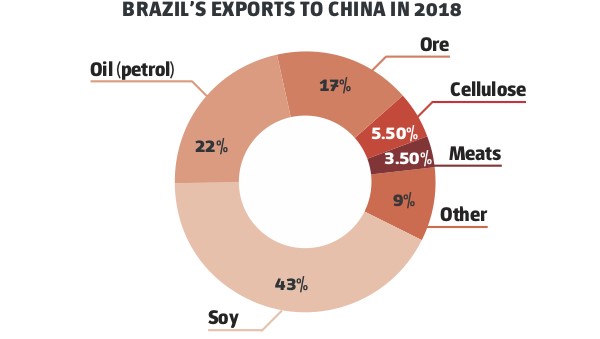

SOURCE: Ministerio da Economia – Industria, Comercio Exterior e Servicios

It’s clear that many Chinese investment decisions are dictated by the needs of the Chinese economy and China’s own long-term development plans — much as Western multinational companies ultimately operate on behalf of their own shareholders. Yet China’s commitments can be particularly volatile and unpredictable. After undercutting local and international rivals to win market share, Chinese construction equipment companies such as Sany announced plans to build plants in Brazil. But at the first sign of a recession, these were quickly scrapped, adding to instability in the sector. “I have no doubt that all this was planned,” said Sawaya, the economics professor.

Perhaps the biggest concern is that Chinese investments and economic ties will cause companies and politicians to act in ways that are counter to Brazil’s national interest. The level of direct political influence over Chinese companies varies but seems to be strongest in big utility companies such as State Grid and Huawei, the telecommunications giant. In both companies, high-level committees — known as workers’ fronts — help ensure that decisions follow guidelines set by the Chinese government. That ensures, in the words of Andrew Davenport, a risk analyst at Washington-based RWR Advisory, that “all oarsmen are rowing in the same direction.” Investors in CPFL were sometimes surprised to find that two people — one from Brazil and one from China — were appointed to senior positions in the company after its takeover. “People used to joke that everybody has a shadow,” said one fund manager who traded the shares.

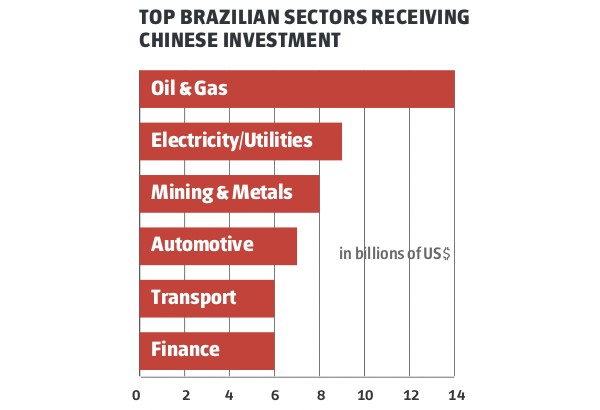

SOURCE: Atlantic Council, OECD

SOURCE: Atlantic Council, OECD

Open Investment Policy

In truth, recent Brazilian governments were fairly blasé about these kinds of dangers. While President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003–10) did move to block big acquisitions of land by Chinese and other foreign investors, the architects of the Workers’ Party’s foreign policy saw China as a valuable ally in its efforts to promote an alliance among the poor countries of the south. Membership of the BRICS — the group linking Brazil with China, India, Russia and South Africa — was enthusiastically embraced. “It was always very friendly. It was quite clear there was a partnership between both governments,” said a former government official who attended several high-level summits between Brazilian and Chinese leaders. While countries like Australia and Germany have recently blocked Chinese acquisitions in energy and other sectors, Brazil has been the biggest Western economy to maintain an open investment policy toward China, according to a recent report by Cebri, a Rio de Janeiro-based foreign affairs think tank. SOURCE: Ministerio da Economia – Industria, Comercio Exterior e Servicios

SOURCE: Ministerio da Economia – Industria, Comercio Exterior e Servicios

Inside the new government, Foreign Minister Ernesto Araújo has been perhaps the most strident anti-China voice. A career foreign service officer who worked for several years in Washington, Araújo has said he opposes the Paris climate deal because such “dogma” favors China. “We want to sell soy and iron ore, but we’re not going to sell our soul,” he told an audience of diplomats in March. Eduardo Bolsonaro, a member of Congress and the most influential of the president’s three sons on foreign policy issues, has taken an even tougher line, saying Brazil drew close to China for “ideological reasons,” much like a previous Brazilian president did with Adolf Hitler’s Germany in the 1930s. Both Araújo and the younger Bolsonaro have met repeatedly with Steve Bannon, the former adviser to President Donald Trump who has said, “We’re at war with China” — and has actively recruited other countries to join the fight.

The so-called anti-globalist wing of Brazil’s government has already charted out a specific agenda. One source told AQ that Bolsonaro plans to seek closer ties with South Korea and Japan as alternative partners. His government will also strike deals with Washington for commodities exports and infrastructure investment that could provide a clear regional alternative to the Belt and Road Initiative, the source said, adding, “That would create a huge stick to beat the Chinese with.” Some work has already started: At a January summit of the World Trade Organization, Araújo criticized the subsidies extended by China to state companies and supported a trilateral initiative by the EU, Japan and the U.S. to clamp down on “unfair competition” by China.

However, there were signs that a different wing is gaining influence in Bolsonaro’s government: the military. Led by Vice President Hamilton Mourão and the even more influential Augusto Heleno, both decorated former generals, this faction sees itself as the apolitical guardians of Brazil’s long-term interest — and thus favors a more pragmatic approach to China, and foreign relations in general. “China has a great hunger for commodities that Brazil produces and for investment to control some phases of the logistics, and so we must make the best of it,” Mourão said. In February, Bolsonaro appointed Mourão to head up a committee to oversee relations with China.

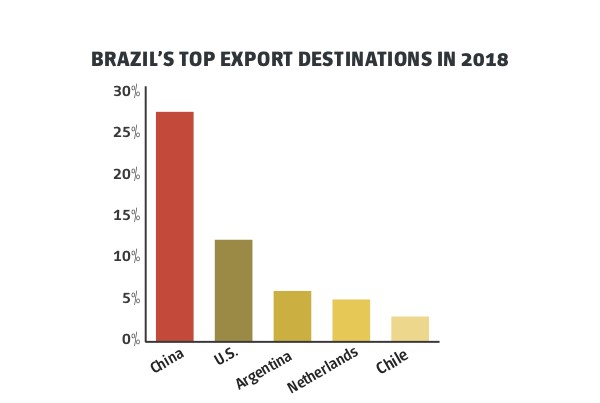

SOURCE: Ministerio da Economia – Industria, Comercio Exterior e Servicios

SOURCE: Ministerio da Economia – Industria, Comercio Exterior e Servicios

One measure of the military’s recent success: a burst of anger from Bolsonaro’s more conservative supporters. Carvalho, the philosopher known for often vulgar tirades on social media, tweeted in March that “the military wants to restore (the dictatorship) under a democratic guise. They are governing and using Bolsonaro as a condom.” Some also voiced disappointment that Bolsonaro passed up a clear chance to talk tough during a March trip to Washington. Asked by reporters about China while standing next to Trump, Bolsonaro simply said, “Brazil is going to keep on doing as much business with as many countries as possible. No longer will business follow ideology, as it used to be.”

Indeed, most signs were pointing to light to moderate change in the relationship, rather than a grand realignment. China may be boxed out of some sensitive infrastructure and technology deals. But that would simply put Brazil in line with many other Western countries at the moment, rather than making it a leader in a new anti-China axis.

Indeed, most business interests were hoping something like the status quo would win the day. Ligia Dutra Silva, the head of international relations at Brazil’s National Agricultural Confederation, told AQ she did not expect major trade disrupton — and was focused on how to expand sales instead. “We don’t want to segregate or distance ourselves from China. We have presented our demands to the government,” she said, “and we have received a positive response.”

Additional reporting by Brian Winter